Gary Hume is walking around the basement gallery of White Cube’s Mason’s Yard branch, where some limestone sculptures are rearing up from the floor: they look like giant worms, with painted mounds jutting out on either side. On the walls are pictures of what look like birds with blue bodies and bright red beaks, painted with Hume’s usual gloss paint on smooth aluminium surfaces, as shiny as sweets. These are the artist’s “paradise paintings”, part of his new London show The Indifferent Owl. And it’s a very particular paradise.

“These are pubescent girls, naked,” says Hume. “These are their legs and that’s their pussies and they’re all leaping across the landscape. I wanted to make some strange paradise where that was possible.” Suddenly those worms look very phallic. Hume ponders their appearance. “They are quite sexual. There’s a plant in America called milkweed. Their pods spew open and all this white stuff comes out.” Yet the sculptures are birds, too – reaching from their nests to their mothers. “They’re overwhelmingly ugly and needy and then they transform.”

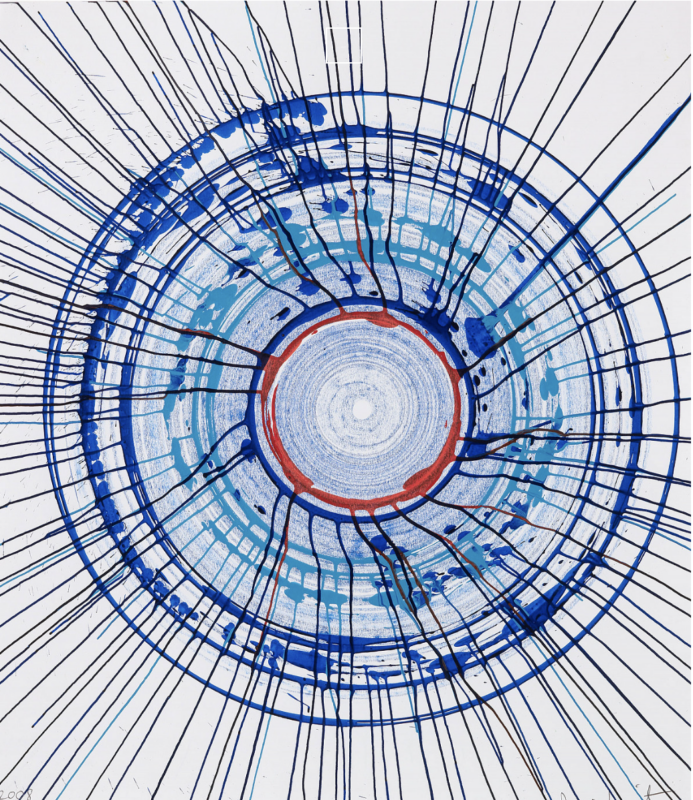

Hume says his work comes from his desire for “beauty and life and sex and little moments”. Upstairs, pictures of blackberries, leaves and breasts hang on the walls; another room contains paintings made in five minutes: intense, draining bursts of creativity. “I’m probably creative for half an hour a day,” he says. “The rest of the time I’m just doing what’s necessary to make that creativity visible.”

Hume graduated from Goldsmiths college in 1988, his work appearing in the seminal show Freeze that same year. Organised by his fellow students Sarah Lucas and Damien Hirst, it launched the YBAs. The Indifferent Owl collects together Hume’s work of the past two years, while a touring retrospective show, Flashback, staged by the Arts Council Collection, kicks off at Leeds Gallery next month. “I’m not as well known as I ought to be,” jokes the man who, by 2001, had been Turner-nominated and represented Britain at the Venice Biennale, “and I’d like to be well-known for absolutely everything. I’m aware my work’s going to be very visible this year, and it’ll be depressing if nobody cares.”

The show’s title comes from Hume hearing an owl hooting outside his home in upstate New York, where he lives for part of the year with his wife, the artist Georgie Hopton. He went for a walk in the woods the following morning, where he saw a deflated party balloon. “The owl had watched it, with this fantastic swivelling head, and was indifferent to this part of human joy that has been let go and is over.”

Hume says it reminded him of himself: knowing that he should be concerned about the world’s problems, but ultimately only really caring about his painting. “Obviously, I have a sense of empathy, but what I’m offering up has no saviour quality. I don’t make political work. I don’t make work that criticises the state. I make as human work as I can.”

I wonder what he thinks of Cameron. “I don’t give a damn.” Really? “I don’t! I don’t vote. I voted Labour once, in that moment of euphoria. I know that if people only made a voice for change then change will happen, but I’m not that person. I’m painting pictures.” One of five children, and brought up by his mum, an NHS surgery manager, Hume says he would never have been able to afford the £9,000-a-year fees today’s students have to pay. “I was on a full grant and I still ended up with huge debts because it’s expensive to make art. Which is terrible – because art school’s meant to be for people who are wrong. You should go because you’re broken. You shouldn’t be going there because it’s a professional choice and your parents can afford it. The disenfranchised should be going to art school – not the franchised.”

Although he was once inspired by magazines and popular culture, and has painted the likes of Michael Jackson and Patsy Kensit, becoming middle-aged has changed things. “If I go out to a bar, people think I’m a minicab driver come to pick someone up. It’s just not my world.”

Curiously, The Indifferent Owl includes a portrait of French poet Rimbaud; it’s one of Hume’s few pictures of men. “Generally speaking I can’t see the point,” he says. “Partly because I don’t fancy them. I have an erotic gaze on women but I don’t have an erotic gaze on a man. Sex is important in my work. There’s got to be a sexual drive in it.” Rimbaud ceased writing poetry in his early 20s. But Hume, it seems, is here to stay. One of the pleasures of being an artist, he says, “is you never have to stop.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.