David Hockney is lounging on a sofa in the studio on the top floor of his beachside house. On the wall in front of him are 18 television screens, all showing films he shot of the landscapes near his home. Does it conjure images of an unchanging blue Californian sky?

If so, think again. For the last few years Hockney has been based in Bridlington, where he has been obsessively exploring the always changing climate of rain, winds, snow – and sometimes sun – of the trees, plants, fields, lanes and light of the East Yorkshire Wolds. Throughout his career, Bradford, the city of his birth, and LA have provided a fruitful creative tension, with a Yorkshire sensibility being applied to west coast mores. (When his mother first visited him in LA, her first question was to ask why no one had their washing out in such nice weather.)

The process has been somewhat reversed in recent years. “Bridlington may be physically isolated, but it’s not electronically isolated. The technology is as good here as it is in LA. Making these films, we’ve started to call it Bridlywood. And while the subject is a very local one, I think my essential interests – in images and how they are made and viewed – have been pretty consistent no matter where I work.”

The bank of screens will form a spectacular ending to Hockney’s new exhibition of paintings, films and work made on an iPad, which opens next week and takes over the entire Royal Academy. On them will be screened multi-camera, super-high-definition footage of the unfolding Yorkshire seasons as well as interior films including a choreographed dance piece by his old friend Wayne Sleep. It is highly unusual for a show of this scale not to be a retrospective, and it is made more unusual in that much of the work was not even made when the show was planned four years ago.

“When we first talked about it I’d never even heard of an iPad, let alone worked with one,” Hockney says. Today he is rarely without his iPad, with its bespoke wooden frame, which functions as sketch pad, full-sized canvas and convenient device for firing off letters to the Guardian on subjects that detain him. “It’s like an endless piece of paper that perfectly fitted the feeling I had that painting should be big. I see now that a lot of the argument in the late 60s was not that painting was dead, but that easel painting was dead. Easel painting means small painting. The moment I got a very big studio, everything took off.”

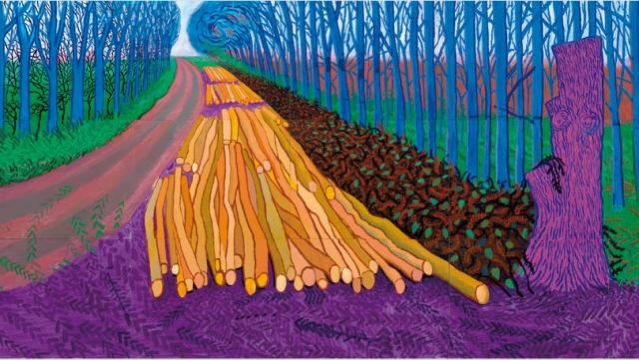

Hockney now works in a huge warehouse on a Bridlington industrial estate that can accommodate work varying from the large to the enormous. So big is the floor area that he has bought a fleet of wheelchairs for him and his team to scuttle around on. He calculates how long he has been back in the UK by the fact that he has “observed seven springs. I’ve watched them extremely carefully and have tried to capture as much of it as I could. One year we missed the hawthorn flower because we were away for a week in May. Another time we were supposed to go to LA in June and the hawthorn hadn’t arrived before we left. So this year I refused to leave Bridlington even for a day.” His commitment to the locality is reflected in the way he has hung the show. “There are also some iPad works of Yosemite in California, but the obvious grandeur of Yosemite will be in smaller rooms than the less obvious grandeur of Woldgate. I like that.”

Hockney was once quoted as saying he couldn’t return to Yorkshire because the days are too short in winter. “I first realised I was missing the seasons when walking through Holland Park every morning while sitting for Lucian Freud. It’s a great subject for artists, but how do you record it? It is too slow for movies, but too fast for a single picture, so it takes quite a few pictures to show the changes. But that’s true of most things. And it’s been a remarkable discovery. I wouldn’t have thought this was a subject even three years ago. But when I found it I realised straightaway it was something that could be developed.”

It is a strategy that has seen Hockney, now 74, finding himself routinely referred to as the UK’s greatest living artist, after a career that started with pop art and went on to define a Californian aesthetic, trail-blazed the use of gay themes, included design work for opera and ballet, made innovative use of new technologies, questioned art-historical certainties about Old Master technique and continues to display a restless energy. His popularity is reflected in a rash of new books: the lavish RA exhibition catalogue, A Bigger Picture, comes with contributions from Margaret Drabble and Hockney himself, there is a book of conversations with the art critic Martin Gayford, A Bigger Message (both Thames & Hudson) as well as Hockney, a semi-authorised biography of the first half of his life by Christopher Simon Sykes (Century).

Last week Hockney twice made headlines: first for supposedly insulting Damien Hirst by stressing that all the work in the RA show was “made by the artist himself, personally”. “It was just a light-hearted thing and I’m not going to pursue it.” And then being appointed to the Order of Merit. He had turned down a knighthood in 1990, but says he agreed to accept this time after the Queen’s private secretary telephoned him to explain that the OM is from the Queen and not the government. “So I had to be gracious, as I think I am a reasonably gracious person.”

But it is a grace that is combined with a combativeness about the issues he cares about, from renaissance optics to the smoking ban. “I did come from a pretty independent-minded family.” His mother was a devout Methodist and his father a socialist activist, first world war conscientious objector and eccentric campaigner who bombarded newspapers – and world statesmen – with letters about his causes, just as his son does today. “He died just before the invention of the fax machine which he would have loved, let alone computers and blogging and all that.”

Hockney says his own political views were set by his early 20s into a “sort of anarchism that took from both the left and the right. Personal responsibility is sort of a rightwing thing that anarchists would support, and so do I. Looking after your neighbour is a leftwing thing, and again I would support that. Ultimately, I’m about liberty and I think you have to defend it. This whole anti-smoking thing just doesn’t add up. The anti-smokers have to deal with the fact that I am still here with a lot of energy. What are they going on about? Some of my colleagues, Picasso, Monet, Renoir, all lived to a ripe old age smoking. My friends have died of alcohol. And it is also terribly bad manners. Smoking is legal, we pay tax and still we’re treated like children. Actually, my father was vehemently anti-smoking, and there’s a film of him trying to take a cigarette out of my mouth, but friends and people who knew him will tell you that we are fairly similar to each other.”

Hockney was born in Bradford in 1937, the fourth of five children. As a precociously talented young artist, his interests didn’t lie with landscape or the countryside – “though I did collect frog spawn and things like that” – but more with the advertising, posters and signwriting he saw around town. As a teenager he won second prize in a national newspaper competition to design an advert for a watch – years later he learned that the young Gerald Scarfe had come first – and he transferred from grammar school to Bradford School of Art. Following in his father’s conscientious objector footsteps, he worked as a hospital orderly rather than do national service. In 1959 he went to London and the Royal College of Art, where fellow students included RB Kitaj, Allen Jones and Patrick Caulfield. He says his upbringing had instilled in him a certain confidence – “certainly enough not to bother when they mocked my accent: ‘Trouble at t’mill, Mr Ormondroyd’ and stuff like that’.” And success came immediately. As a student he exhibited in important shows and sold work. When he left the Royal College – having been awarded its gold medal – he was taken on by the fashionable dealer John Kasmin and quickly became one of the best-known figures in what was turning into swinging London. But he still felt the city was only a staging post.

“I arrived in September 1959, but by the summer of 1961 I’d spent a few months in New York” – resulting in an early set of etchings updating Hogarth’s Rake’s Progress. “As soon as I got there I realised that this was the place for me. It was a 24-hour city in a way London wasn’t. It didn’t matter where you were from. I absolutely loved it, and then when I went to LA I liked that even more. So when swinging London was going on, for most of it I was actually in California. And I never thought London was that swinging when I did come back. It was for a few people, but in LA it was for the many, which I preferred. In LA in 1964 there were enormous gay bars. There wasn’t anything like that in London, or even in New York.”

By the mid 60s Hockney had embarked on some of the paintings with which he will forever be most associated – of the swimming pools, the boys, the blue skies and beautiful people. Works such as A Bigger Splash and the large double portraits of subjects such as Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy not only crystallised his artistic vision, but also California’s vision of itself. And he says it was not coincidence that this work emerged while he was living at the heart of the film industry. “I caught the end of the great period of Hollywood, which ran from 1920-1970. They made some masterpieces, and whether they thought they were making art or not, they were great picture and image makers.”

Hockney was friends with the director Billy Wilder – “directors are much more interesting than stars. Billy used to say ‘show me a bright actor and I’ll show you a bad one'” – who introduced Hockney to “old Hollywood. But Billy has now gone and there won’t be people like him again. Quite a lot of the little worlds I knew well have now gone: Christopher Isherwood’s, Tony Richardson’s, the world around Joan Didion. So when I go back to LA now it’s a little different. Because my hearing has gone I can’t socialise like I did, but I still like LA and America is still an energetic place. It’s gone overboard with the anti-tobacco thing and they are all a bit doped up with antidepressants since they stopped smoking, but it can still be an incredibly creative place because it is still free and it will always benefit so long as it stays free.”

Hockney’s deteriorating hearing contributed to the premature end of his career as a designer for ballet and opera that began with his now much-revived Rake’s Progress at Glyndebourne in 1975. But, characteristically, it has also prompted a few theories. First that his visual perception has actually improved as his hearing has declined. “Someone who can’t see locates themselves in space through sound. If you can’t hear you locate yourself visually. And as someone attuned to the visual world it is very noticeable. I see more.” The second theory concerns his hero, Picasso, who once said that music was the only art in which he couldn’t tell which were the masterpieces. “So he was obviously tone deaf. But while he couldn’t hear tones, he obviously saw more tones than anyone else because his grasp of chiaroscuro was stunning, as good as Rembrandt.” Hockney never met Picasso – “too in awe of him. Why would I waste his time?” – but he remains for him the greatest artist of the 20th century. “Not only was he the best painter, he was also the best sculptor. I still don’t think we’ve fully grasped what he achieved, and, of course, he would have absolutely loved something like the iPad.”

Hockney makes the point that both a paintbrush and an iPad are “technology”, but he has been a determined early adopter since the mid 60s when he started to use a camera as an aide-mémoire. By the early 70s he was making his first “joiners” – large assemblages of photographs that produced an almost cubist effect – in response to his dissatisfaction with the distortion of wide-angle lenses and was quickly aware of the possibilities of office-quality photocopiers and the fax machine. He has also made art-historical investigations into image making that have taken in the study of Chinese scrolls, has conducted a long critique of photography and engaged in a prolonged study of the use of optics by Old Masters that culminated in his 2001 book, Secret Knowledge.

He argues that his own multi-camera work is not that far away in essence from what Caravaggio was attempting. “Caravaggio had the equivalent of nine cameras. They are collages. By the time you get to Vermeer it is one camera, like we have today. With nine cameras your eyes watch in a way they don’t with just one. You continually scan and you look much harder. And in a way it is more like drawing. There are questions of composition and infinite ways to do it.”

His interest in the creation and the power of images also informs another theory. “Art history feels as if it has stopped because it doesn’t know how to deal with photography and therefore how to sort out today. But if you just look at the history of images then it becomes much easier. For 500 years the church had social control because it was the main supplier of images. You can point to Darwin, but social control moved with the control of images in the early 19th century to what we now call the media: newspapers, then Hollywood and television. There is now another revolution and the images are moving to individuals. Mr Murdoch will lose his power just as the church did. It might cause terrible chaos. What happens when authority leaves? We don’t know. But we do know that nothing is for ever. Even though I’m hidden away in Bridlington, which I like a lot because it is hard for people to drop in and you can get a lot of work done, I can watch it all.”

Hockney had regularly returned to the area to visit his mother, who died in 1999. He now lives, with his partner of over 20 years, John Fitzherbert, in the large converted guesthouse he bought for her. “I lived in LA so long I’ll always be an English Angeleno, but to me now the big cities are less interesting and sophisticated than they were. To get something fresh you have to go back to nature. When they say the landscape genre has been done, that is impossible. You can’t be tired of nature. It is just our way of looking at it that we are tired of. So get a new way of looking at it.”

Soon after returning to Bridlington Hockney completed the giant – 40ft x 15ft – painting Bigger Trees Near Warter for the 2007 Royal Academy summer exhibition and the following year donated it to the Tate. It is an indication of the scale of his recent productivity that it is not part of the RA show. He says that after the show opens he has planned one of his regular trips to take the waters at Baden-Baden. “I can go in on my knees and come away dancing. But if I’m honest, the work itself keeps me going as much as that does. My theatre colleagues would always slump after a show opened. But I am always on to something else.” He says his rediscovery of landscape and new ways of capturing it is “as fascinating and exciting as anything I’ve ever done. Even after the Royal Academy I’m not going to stop with this work and so I don’t really have time to do low. It’s been wonderful to find a place like this where I am pretty much left alone to do what I want. When my friends in LA ask me what I am doing, I say I’m on location. They understand that, even if it has proved to be rather a long shoot. But you get to a stage of life when that’s what you want. Monet stayed out at Giverny, Cézanne was in Aix, Van Gogh stayed in Arles. You might need a big city when you are young, but there comes a point when you need somewhere else. I’ve found it here.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.