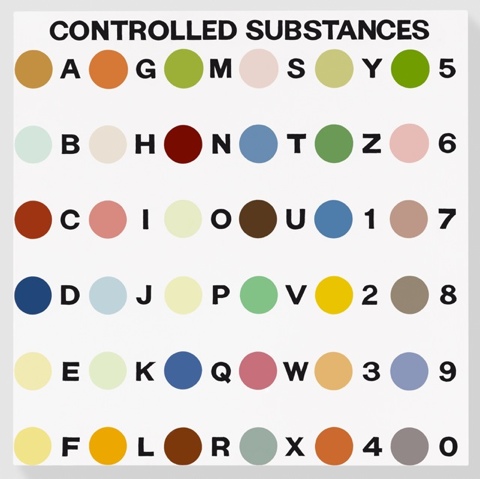

Damien Hirst Controlled Substance Key Painting, 1994 Household gloss on canvas 48 x 48 inches 121.9 x 121.9 cm Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2011 Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

The titles of Damien Hirst’s spot paintings give them a slightly menacing, as well as a dangerously attractive, air: Cocaine Hydrochloride, Morphine Sulphate, Bovine Albumin, Butulinium Toxin A. Their relentless, insistent brightness feels almost bad for you. No wonder one group of paintings is called Controlled Substances. Yet they have no discernable secrets, and that’s part of the deal. Nothing more is revealed, however long you look. They’re as unsatisfying as cigarettes, calming but addictive. Avoid prolonged exposure.

Opening today at all 11 Gagosian galleries around the world, including two in London, Hirst’s spot paintings are taking over the planet. Hirst has produced almost 1,500, and currently has a team of assistants working on one with a million spots that will take over nine years to complete. You gasp at the labour, if little else.

So here come the spots: a quarter century of two, three, four and five-inch circles, with some as big as 40in across, and others just a couple of millimetres. Never mind the shifts from imperial measurements to metric: they’re all just spots. Clean and flatly painted circles of household gloss on white or off-white backgrounds, they cover canvases large and small in unremitting grids. No two spots touch, and no colour is repeated on the same canvas, although some are close as dammit to being the same hue.

There are tiny one-spot paintings, paintings with spots at their corners, ones covered with rank after rank of hundreds, if not thousands, of little circles. There are big spots that go BAM! and others that recede, their pallid colours melting into the background. There are fields of tiny spots that give the overall impression of a greyish muted field, and great blasting walls that go on and on, blinking away as you move about them. Because the colours never touch, there’s no real conversation or friction between them. Everything is insistently frontal. I long for a black spot, a wobble, a smear.

Some paintings might look perky, others dour, but somehow it doesn’t matter, except to those who want a particularly early painting, an over-the-sofa one, one that goes with the curtains, or one with no purple in it (it’s my unlucky colour). It may turn out that, taken all together (and one journalist, I hear, is intent on making the rounds of every Gagosian gallery to see all the paintings), the work of one or another of Hirst’s assistants may have produced the best spot paintings. But is there a best or worst? How can we tell? Each has the same pictorial and optical efficiency, the same immediacy, even though they are so laborious and painstaking to produce.

In London, there are 60 paintings at Britannia Street and 48 in Davies Street. The latter has paintings small enough to carry under your arm or hide in a pocket, if they weren’t screwed to the wall. Hirst’s earliest spot paintings, I gather, are at the Madison Avenue gallery in New York. His first one was all hand-painted blobs, jostling, dripping and crowding an 8ft-by-12ft panel, painted while he was at Goldsmiths college, London, in the 1980s. It had a crowded, rhythmic yet open look you could get lost in, a bit like the early 1960s work of British painter Bernard Cohen, himself no stranger to the blob and spot.

But Hirst’s spots soon acquired a clean and emphatic air. These were take-it-or-leave-it paintings, without problems or doubts, painted directly on the wall. He was doing lots of other things at the time, including painting on discarded cardboard boxes and producing his first medicine cabinets. The variety and inventiveness was evidence of an enquiring and lively mind. Lots of artists could make a whole career from such an apparently limited repertoire of forms and effects. But Hirst, of course, keeps several artistic modes running at once. This spring, a retrospective opens at Tate Modern, while Hirst intends to open his own museum in London’s Vauxhall some time soon.

No matter how many spot paintings there are – tondos, triangles, squares, rhomboids and rectangles with corners cut off – there will always be more words spilled over them. The works look as if they were generated by machine, their cold random repetitions generating endless sameness. It is only the very small works, some with just half a dot on a tiddly canvas, that have a more sprightly, human feel.

All are structured on the grid. The grid, wrote the US critic Rosalind Krauss, is what art looks like when it turns its back on nature. The pleasures of Hirst’s pharmaceutical paintings, as the spots are generically titled, are as artificial as chemicals and drugs. Showing them all over the world at the same time becomes part of their content and meaning: they’re infiltrating everywhere, their field expanding to cover the world.

For a while, coloured spots signalled a fresh, sophisticated, zesty new Britain. Whether Hirst had much to do with this is uncertain. No one owns the spot, although designer appropriations always remind you of Hirst, or of the Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, who has been covering her work, and her body, in polka dots for 60 years. (Kusama is at Tate Modern next month.) US artist Ellsworth Kelly was also arranging grids of colours in the 1950s, while Germany’s Gerhard Richter has been painting colour charts and squares for decades. Hirst just ran with an unoriginal idea in an original way. Which, pretty much, is what art always does.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.