A New Year’s resolution: own up to ignorance. I freely confess that I had never seen anything by Cecilia Edefalk or Gunnel Wåhlstrand until the first week of 2012. I would have been hard put to say what kind of work these Swedish artists even made. But if the show of their paintings at the Parasol Unit proves anything at all it is that there is still art out there that needs no introduction, no explanatory preamble or wall text or foreknowledge of any sort. This is art that speaks beautifully for itself.

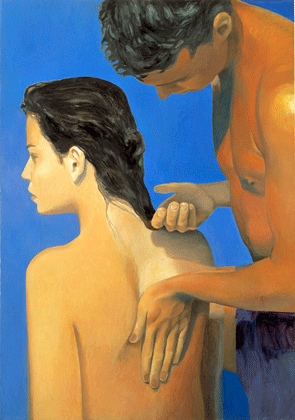

Edefalk makes extremely concentrated paintings that hold the eye with their elusive imagery – a solitary woman, arms raised as if sleepwalking or possibly in levitation; a stone statue beneath a canopy of ivy and snow; a girl who appears to be protected by a golden wing, except that this wing turns out to be a haze of bees brushing softly around her. The elements may have their origins in photographs, but each painting overrides the documentary truth to present something far stranger, more like a vision or half-remembered dream.

What is singular, and striking, is the peculiar strength of these figures, which somehow hold their own in the suffused light of Edefalk’s paintings. For her palette – white, grey, silvery blue and taupe with the occasional wash of yellow – is spectrally pale and tonal. On the other hand, there is scarcely any detail and no context to explain (and thus limit) what you see, so the subjects retain their mystery.

The paintings come in series, what is more, running from small to monumental as if created in editions. You are instinctively drawn to spot the differences. But again, this is not about simple details. As the pictures are put through their paces – paler, larger, more or less figurative, suspended upright or sideways – they appear to perform in relation to one another.

The stone Venus registers firmly in one canvas, less resolutely in another and as little more than an empty silhouette in a third. It is as if the paintings are having trouble remembering her. In another sequence, a portrait of an alert and dark-eyed woman is reprised and distorted over and again, each image seeming to originate in the one before. The last is upside down and yet that dark-eyed stare remains legible, recognisable, the one fixed note. Echo is the collective title.

Viewers familiar with Edefalk’s work may be aware that Echo is, in fact, a self-portrait, but it has none of the familiar eye-to-eye intensity of the genre. There is no sense of the artist wishing to communicate, to be known or understood. Quite the reverse; if the sequence expresses anything at all it is the mutability of the self, the difficulty of summing oneself up in a single, definitive image.

If you do want to know something about Cecilia Edefalk, you can probably deduce most of it from the show’s sparse labels. Born in 1954, and one of Sweden’s leading painters, she is either very slow or highly selective about what she makes as precious few paintings exist, almost all of them in public collections.

She took nearly a decade to produce the 12 Venus pictures, which all return to the same moment when she saw a flash of light illuminating a silhouette in a wintry London garden. So the statue was a shadow in the first place, just the recollection of a brief phenomenon.

Venus comes and goes, now curvaceous, now a stark white cutout. The canvases appear frost-blanched, faded, patinated, rubbed away. The paint describes: the paint erases; the analogy with memory is implicit. And each picture has a relationship with the next something like our own viewing of the world: attentive, fascinated, distracted, altered daily by experience, continuous and ever?changing.

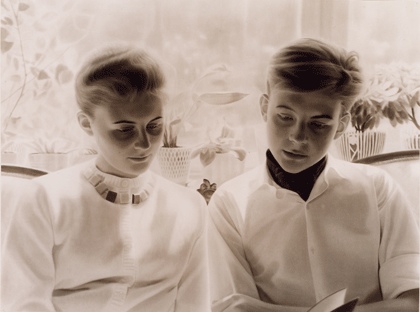

Upstairs at the Parasol Unit, and perfectly matched with Edefalk, is the monochrome art of Gunnel Wåhlstrand: immense images faithfully, painstakingly, based on old family photographs. A mother with a marcel wave, a daughter dressed in box pleats, a son in blazer and bow tie. It might be the 50s, and it might be any well-heeled family if the art did not declare it to be otherwise.

Two children by a window appear almost supernaturally bright, as if the daylight was glowing from somewhere inside them. An impeccably groomed schoolboy at a desk has all his attributes around him – the globe, the books, the model aeroplane taking off for ever on its stand. Our boy sits heroically still for the record. Even the animals on the waste bin look like mythical beasts. The moment is caught as it passes into history.

Wåhlstrand (b. 1974) paints in ink-wash on paper. Her vast transcriptions are a feat of exactitude and loving labour, admired in Sweden since her graduation show in 2003. The ink tinges the paper with a great range of nuances from silver and dark grey to something approaching sepia. It’s the twilight of old films, catching the gleam of immaculately brushed hair, spangling teeth and spectacles, finding haloes in polished floors.

And the narrative develops: the same boy, the same girl, by now a little older, perfect teenagers in a silent apartment, the clock ticking, the ghostly reflection of someone holding up the flash, the melancholy overtones of Bergman.

The scale invites you to enter deeply into each scene, but the photographs put a limit to that search. All you can see is all that Wåhlstrand can show in these beautiful commemorations, as she pores over the minute details of the past but cannot make more of them than each photograph discloses.

Except, of course, that her own images form a story in themselves, a tale of perfection and froideur in which the boy appears isolated in every room of the house. The knowledge that Wåhlstrand’s father took his own life when she was one might make the paintings more poignant to some, but I doubt it. They are profound remembrances of moments lost and lives past.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.