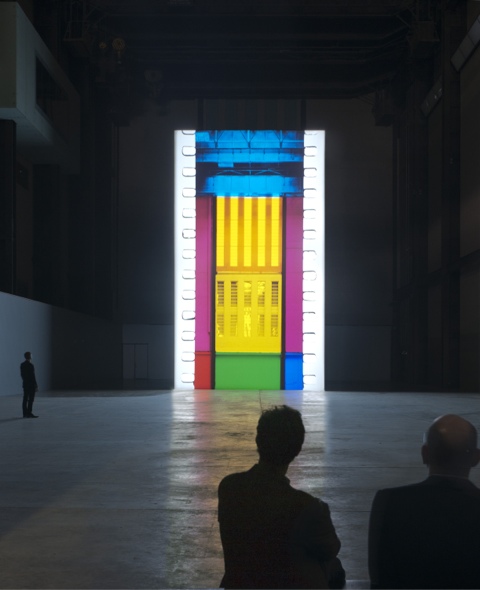

Tacita Dean FILM 2011 Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris. Photo: Lucy Dawkins

I saw incredible things on Christmas Eve. A train sped towards us in black and white. A rocket embedded itself in the eye of the man in the moon. Harold Lloyd hung from a clock.

These are all famous scenes from early cinema, and it wouldn’t be so unusual to see them on DVD or YouTube. What made it special was that I saw them projected on a giant screen at a cinema in London’s Leicester Square.

Martin Scorsese’s film Hugo uses the newest film invention – modern 3D – to tell a story about the first days of cinema. Within this narrative, it shows early films by the likes of the Lumière brothers not to film buffs at festivals or as stills in history books but to a young audience (this is a film for kids) on commercial screens.

Hugo is Martin Scorsese’s best work in years and a profoundly moving defence of the magic of film. To be honest, I was crying behind my 3D glasses when the films of Georges Méliès returned from the past on to the huge screen. It’s a great movie moment. Scorsese uses 3D to recreate the shock and wonder of the first time people saw moving images. After showing the Lumière brothers’ train that scared audiences who had never seen a film, he creates a comparable terror in 3D – something we ourselves have never seen before.

At once preservationist (the old films must live on) and futuristic, 3D – which has been losing audiences put off by shoddy usage of it and higher ticket prices – has no better champion than Scorsese. Hugo proclaims that today’s technology can offer new artistic beginnings – a return to the original wonder of the “flickers”.

It is a seductive manifesto, because Scorsese is so passionately in love with cinema. And I could not help contrasting it with Tacita Dean’s Film at Tate Modern.

Dean shows a montage of beautiful images that she created, edited, and projects on celluloid. Her installation is a lament for the lost art of making films on film and a protest at the replacement of celluloid by digital memory. For her, the craft of film-making is physical. It carnally attaches itself to real faces and places. The digital revolution means a death, which she mourns.

Hugo is not “about” celluloid, although the preservation of early film stock does feature in its story. The parallel is that both works of art – Scorsese’s Hugo and Dean’s Film – look back on cinema history at a moment when new technologies are transforming what cinema is. For Dean, what she loves about cinema is dying in a brutal purge of celluloid. Yet Scorsese – who undoubtedly loves the same things about film that she does – sees new possibilities, new magic, and new ways of celebrating and preserving history, in this miraculous 21st century we inhabit. Scorsese’s vision gripped me more.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.