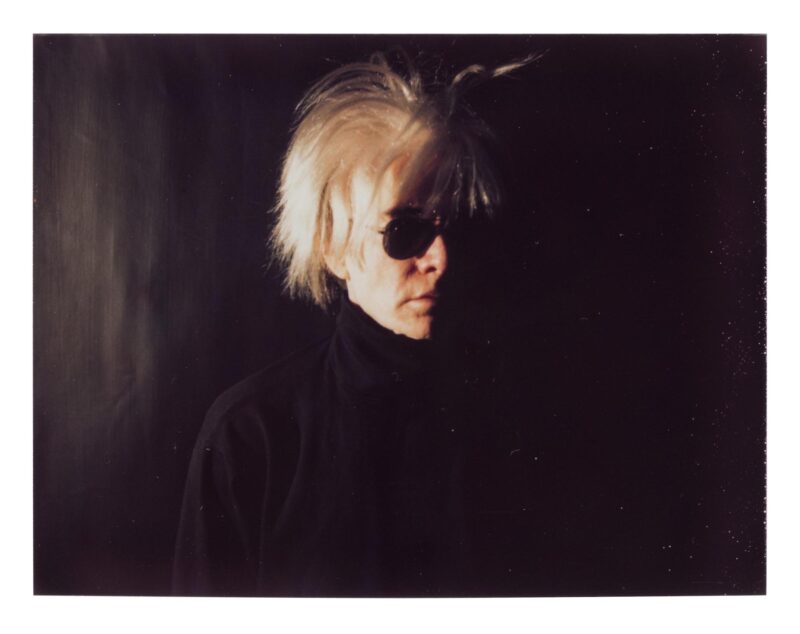

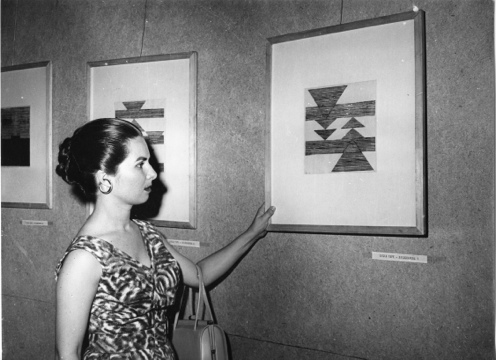

Lygia Pape at the National Exhibition of Concrete Art, 1956.Published in Cruzeiro magazine. Vintage photography. Projeto Lygia Pape© Projeto Lygia Pape

It is hot in the Serpentine Gallery this winter, hot but surpassingly cool. The work of the Brazilian artist Lygia Pape flies you down to Rio in the 60s. Bronzed boys and girls fool about on the beach, waves glittering on the shore. Artists in John Lennon specs mount spontaneous happenings. A woman in a headband hatches out of a white cube, sunlight sharpening her shadow in the heat. The soundtrack is all João Gilberto or flanged guitar.

Pape (1927-2004, and pronounced “pah-pé”) is one of Brazil’s most celebrated artists. She made paintings, constructions, woodcuts, performances, films, ballets and highly comic architectural models. Although her short films are dense with friends and family, hamming, cavorting and generally acting up, she was a pioneer of non-figurative art, active in both the concrete and neo-concretist movements along with fellow stars Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark.

Indeed, if you have seen Pape’s work in Britain at all, it will likely have been in a show devoted to these avant-gardists of the 50s and 60s. They have something in common with the Japanese Gutai group, America’s Gordon Matta-Clark and Italy’s arte povera, all of them intent on quasi-utopian projects that were often impromptu, generally devised from scrappy materials and aimed at an audience beyond the art world.

Pape, for instance, is well loved for a project she organised in 1967 with the children from a favela near the street where she lived. It involved nothing more than a few dozen cotton sheets stitched into a single white cloth, plus a rolling camera. The children were invited to stick their heads through holes cut in the fabric and then to walk forward together.

The effect is at first funny, as these little heads pop up all over the place, and then affecting as they begin to move. The children are joined and yet separated, a sea of humanity, morphous and amorphous, singular and collective. With each wave comes a new face, a new expression, and yet each depends upon the other to keep the flag flying, as it were, to keep the project alive and the movement flowing onwards.

Over the decades, this piece has been interpreted as a comment on capitalism, communism, bureaucracy, even the split between mind and body. It clearly looks quite different according to time and place. Nor is it immediately obvious from the startling juxtapositions of Catiti-Catiti, made in 1978, just how the work should be understood politically, given that Brazil was in the grip of a 20-year military dictatorship. The film splices footage of surfers in white swimwear with Esso signs, images of the jungle and wild track of a long-haired man – read artist – monkeying around with bananas, stuffing raw fish in his mouth and generally baffling the local street kids. Modern eyes might recognise Marcel Duchamp playing chess but not (or not in my case, alas) the allusions to cannibalism, still less the references to kitsch tropical art.

Murky, grainy, and with jump cuts so rough the effect is positively quaint, the work cannot help being a period piece. But it also feels peculiarly vital and jaunty. So it is with many of the films at the Serpentine – the fake vampire movie, the beach scene in which Pape clambers out of her white cube of an egg, or bleeds from the mouth with what is clearly food dye. This is radicalism with humour, the Brazilian avant garde with a twinkle in its eye.

Brazil saw early European abstraction for the first time in the 50s, as Malevich, Mondrian and the Bauhaus school were shown at the São Paulo biennials. What Brazilian artists made of this geometric rationalism was as sensuous as Gilberto’s music – suave constructions, floating grids, paintings that fairly danced.

Pape’s little wooden constructions invoke all these European forebears. Combinations of the circle, square and triangle, intercut, inlaid and painted in the primary colours, plus black and white, they unfold across an entire gallery wall like some new language in unending permutation. The Book of Time, she called it.

Her woodcuts on transparent paper consist of fine lines darting in one direction, encountering blank white squares, or lines running in the opposite direction. Geometric, minimal, elegant, they conjure light, music and rhythm; crumpled, disposable, of slender means, they also look like a lightsome retort to early Frank Stella.

Pape studied architecture, and then miniaturised its idioms in pop-up paper models: baroque curlicues, modernist Möbius strips, a Greek temple of pleated card. Best of all is Oasis, a little green cube all alone on a sheet of sandpaper. It looks like child’s play – and that is partly what Pape seemed to aim for. Her art aspires to an ideal simplicity, an uncomplicated joy, though of course it is achieved through practised sophistication.

Some of the exhibits in the Serpentine show remain irretrievably opaque. It is hard to catch the spirit of the age from elderly photographs and records of events long ago and, for some reason, Pape’s most explicitly political works are not included. This is a pity, as they would have given a clearer sense of her ideas.

This is, what is more, a cut-down version of an immense show from Madrid’s Reina Sofia museum, and it cannot help but suffer from the downsizing. It would take more than the compact dimensions of the Serpentine to show off Pape’s energetic range and versatility – the ballets, the curtains of fruit, the geometric sculptures, the gatherings.

Still, it contains a real coup de théâtre, likely to be the main delight for anyone visiting. Made in 2002, it connects the late works right back to those minimal woodcuts of the 50s. In the central chamber of the Serpentine Gallery, shafts of golden light appear to filter down through the darkness; moonbeams, perhaps, or something more celestial. Made of nothing but threads, stretched and shot through with light, they are utterly simple – and transcendently beautiful.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.