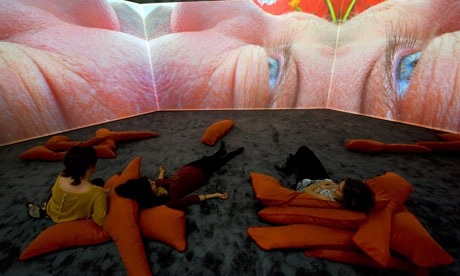

Visitors watch Pipilotti Rist’s Lobe of the Lung. Photograph: Linda Nylind

A miserable bunting of underwear flaps in the breeze outside the Hayward gallery in London, like washing hung out to dry. Nearby, globular grey bubbles spill from a machine on the outdoor sculpture court, wobbling and writhing as they ascend over Waterloo Bridge. The bubbles burst in puffs of smoke. Life, it appears, is nothing but pants and smoke.

Inside the gallery, the first thing you see is a sort of chandelier of undies, dangling from the high ceiling. A knicker-sniffer’s up-skirt fantasy? No, this is Massachusetts Chandelier by the Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist, whose wonderfully exuberant and sometimes alarming survey show opens here this week. Underpants, Rist says, are the temples of the abdomen: “This part of the body is very sacred, the site of our entrance into the world, the centre of sexual pleasure and the location of the exits of the body’s garbage.” How true, how very true. Marks & Spencer should use it for their next lingerie ad campaign.

Rist delights in the provocative. After the chandelier, her world bursts into colour. Down on the floor there is a projection of a woman’s body. The camera homes in, turning as it delves into her lipsticked mouth. Unexpectedly, the next thing we see – just for a second – is the woman’s puckered anus. Glop! And then we start circling her mouth again. It’s a lot more fun than that film Mona Hatoum once made using an endoscope.

Rist’s work is visceral, earthy, sexy, full of life. Up on the mezzanine, I lounged on body-shaped cushions, pairs of stuffed jeans and headless upholstered torsos, plumping them up in vaguely orgiastic piles. It was soothing to lie there, amid a labyrinth of diaphanous curtains, with projected images wafting and rippling over their surfaces. It felt like nap-time at kindergarten. You have to be a miserabilist – and I admit I’m a sucker for art’s bleaker regions – not to take pleasure in Rist’s warm baths of light and nature, her sunny fertile fields and underwater rebirthings, her gleeful swooning mischievousness.

Flocks of sheep, marrow flowers, blue skies and sudden showers of sparks, as if a welder were at work in some corner of paradise, floated by. I think I nodded off for a bit. Music drifts through the galleries like aural valium. Next thing I knew, I was dancing in another installation, against a translucent wall on which all sorts of images erupted and glistened. Water and naked bodies, crushed tulip petals and insect-eye views of a well-tilled field. Did I just see a pinky-brown earthworm coil and stretch about a woman’s nipples? Did I just see a glob of menstrual blood dripping into the pond?

Installation is too po-faced a word for Rist’s environments. If all this sounds like the tedious record of some acid-frazzled trip, she is just as capable of bringing you down with a bump. Her art is more serious than it often feels. There are worms in the apple, anxieties afoot, a bomb in the infant’s cot. This is a real cot, and the spherical mine with its spiky protuberances turns out to be another video screen, alive with rearing sexual images. Childhood innocence is not so innocent. The bomb could also be a model of a giant virus molecule. Her works infest and infect the galleries. There is even one in a cubicle in the women’s loos: sit down and a little woman waves up at you from the floor between your legs.

Minnie Mouse sings the Beatles

In one early five-minute student work from 1986, you have to stick your head through a circular hole in a gigantic stucture that projects from the wall, a sort of zooming pyramid. Rist is in there, performing a Minnie-Mouse clod-hopping dance routine. Her breasts are exposed and she’s singing “I’m not a girl who misses much”, over and over, all speeded-up, high-pitched and frantic. The line she sings is from The Beatles’ Happiness Is a Warm Gun, and John Lennon’s voice comes in at normal speed towards the end.

There’s something hysterical about all this, but then women are often accused of being hysterical when they tell unpalatable truths, or assert themselves. Rist is uncontained and won’t be boxed in; she doesn’t miss a trick. Instead you are the one who is trapped, watching this with your head stuck in a hole. Another video is visible through a tiny splintery hole in the floor, a little dot of beckoning brightness. Rist is down there, screaming in a far-off voice. I cover the hole with my ear. “I am a worm,” she shouts. “You are a flower.” She seems to be naked, with volcanic lava boiling all around her. Pipilotti Rist has issues. Who doesn’t?

What keeps coming back again and again is that this is the work of a woman, centred on the feminine. There is a strong sense of an all-encompassing and limitless female sexuality. I feel absorbed and lost in it, at moments almost dangerously infantilised, my body diffused. You look at video images half-hidden inside handbags and conch shells, and obvious though these Freudian tropes may be, Rist’s dream-scenes are consuming. No man would or could make art like this. Its closest equivalent (and its obverse) would be someone like the Los Angeles-based Ryan Trecartin’s trashy, perverse, ecstatic video work. Both artists give you too much; both are dizzying and overwhelming.

A shout for bodily pleasures

Rist’s art is a great corrective to the pieties, decorum and conceptual heavy breathing of current “serious” art. It is a shout for bodily pleasures and sensuality, sometimes to the point of silliness. Her work is as addictive as the Tellytubbies, and occupies a similarly wonky psychological zone.

The streetlights are coming on and there is an orange sunset smear across the sky. There is a light, tinkling music, giving the gallery a slightly stoned, holiday air. On a small screen, Rist is in a car, talking about families and relationships. On the wall behind, highways and skies and trees tilt by. The things Rist says are depressing: stuff about babies making everything OK, couples not kissing, and then being together till they rot. Should relationships end, she wonders, precisely when they are at their best?

On the floor in front of this screen is a model of a perfect modern house, the kind Rist grew up in. It sits in the middle of a compound and reminds me of a prison. Looking through the window, you can see a video of supper being served. The plates are all on fire. The house is a model of a perfect Swiss suburban dwelling. There is even a road, with model streetlights marching towards the far wall. You could trample all over it, smashing your foot through the roof of the house. Life in the suburbs can drive you crazy.

The New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl has described Rist as an “evangelist of happiness”. She is more than that. Her work is seriously crafted and paced, as generous as it is dangerous. We are, she has said, “permanently juicy machines” – and you can’t really argue with that.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.