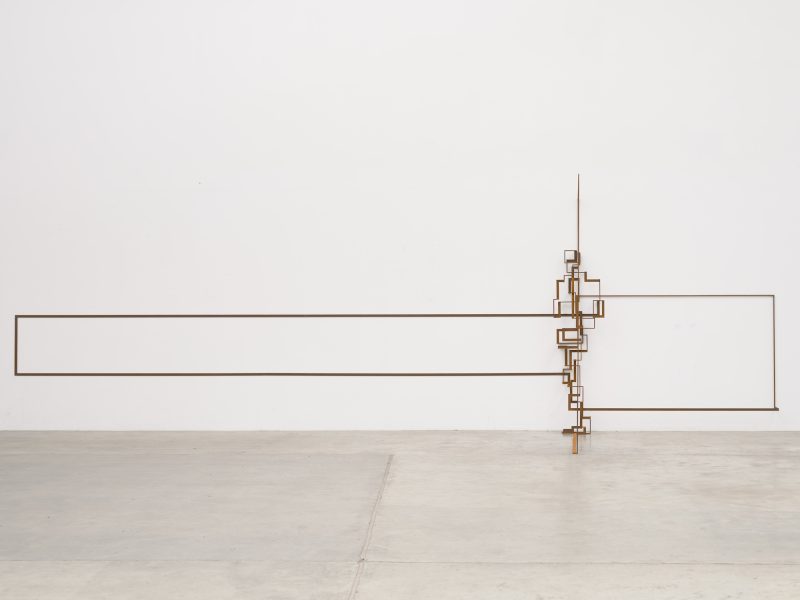

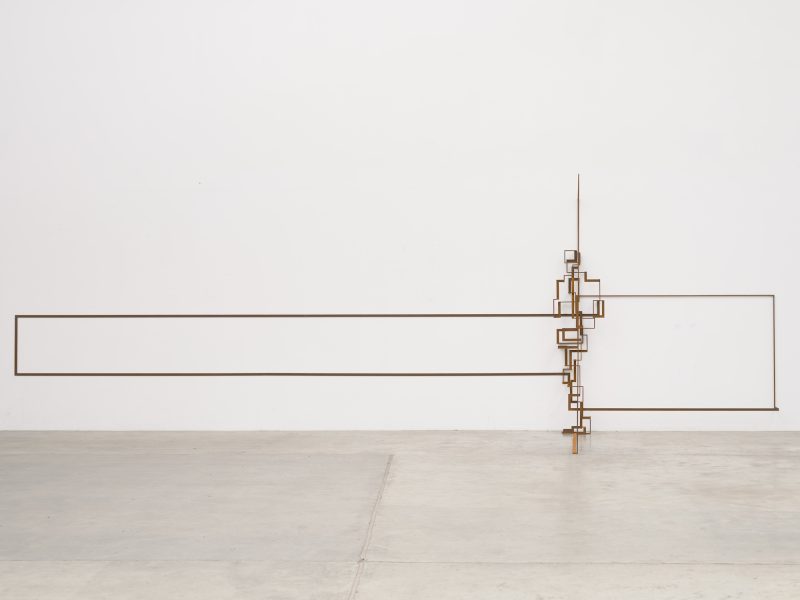

Image:Raqib Shaw The Moonbeam Gatherer [detail] 2009-11 Oil, acrylic, glitter, enamel and rhinestones on birch wood 60 x 191 15/16 in. (152.4 x 487.6 cm) © the artist Photo: Ben Westoby Courtesy White Cube

28th September – 12th November 2011

‘Paradise Lost’, a new series of work by the London based artist Raqib Shaw. Historically, John Milton’s epic poem, based on the Fall of Man, has inspired artists such as William Blake or Gustave Doré, yet Shaw steers away from this grand narrative to create a visionary ode to his own childhood memories and imaginary paradise.

A departure point for the new series of work is ‘The Mild-Eyed Melancholy of the Lotus Eaters’ (2009-2010) which refers to Homer’s ‘Odyssey’ and more directly, the poetry of Alfred Lord Tennyson who described the narcotic effects of the lotus flower when eaten by a group of mariners. Shaw depicts a pond carpeted with lotus flowers that appear to have intoxicated the various creatures and figures, languishing in a state of carnal inertia.

Amongst the rampant pond life, lotus flowers reappear in the two pools of ‘Narcissus’ (2011) based, in principle, on those found in the gardens of Versailles. Presented in the ground floor gallery, these exquisitely painted bronze sculptures mirror each other as a swan lurches over and pecks the innards of a hybrid man, whose vampire features scream as blood streams from his brutally gouged out eye-sockets. The figures cast from the body of the artist, tentatively balance on one foot like a Hindu Chola bronze of Nataraja, the dance of the destroyer. Shaw revises Ovid’s account of ‘Narcissus’, the moment when a lone youth first admires his reflection while drinking from a pond to this endangered moment of self-discovery, where in union these blinded figures are castrated from seeing their own agony and demise. This mortal combat also draws comparison with the Greek myth, the rape of Leda by Zeus and the death scene in Tchaikovsky’s ballet ‘Swan Lake’. Partly inspired by the King Ludvig II of Bavaria whose insignia was the majestic swan, the ballet’s moral battle of good versus the evil here is subverted as the black and white birds attack with mutual voracity and violation.

Shaw stages his ‘Paradise Lost’ paintings according to a specific time, climate and season. On one side of the gallery, three paintings depict a wintry mountainous nightscape, centrally lit by a full moon while on the opposite wall, spring blossoms as the sun creeps over the horizon. These paintings are mirrored in format as two octagon-shaped paintings sit either side of an elliptical panorama, each depicting a lone or contemplative character attempting an impossible feat. One waits attentively for moonbeams to drop in to an ornate chalice while another swings from the trees randomly catching the falling blossoms or one of the many circling swallows. All these figures appear preordained or literally bound to these futile tasks while the wildlife actively seek and attack their prey of all denominations.

The culmination of this imagery pours into the first chapter of the trilogy ‘Paradise Lost’ (2011), Shaw’s largest painting to date. Here the viewer embarks on a journey from the aspirations of the lone figure who alongside a wolf howls before the bitter moon to the natural carnage as the dawn breaks. Shaw heralds all this by depicting the release of a single nightingale from its cage, a bird favored by the poets as creative with a spontaneous song. Then, as seasons pass, a flight of swallows migrate south symbolizing an inherent free spirit and desire to return to a place of origin. This notion is at the heart of Shaw’s paradise – a romantic yearning for a bygone era, where innocence and beauty prevailed – a personal mythology that embodies hope, disillusionment and the underlying entropy of life.