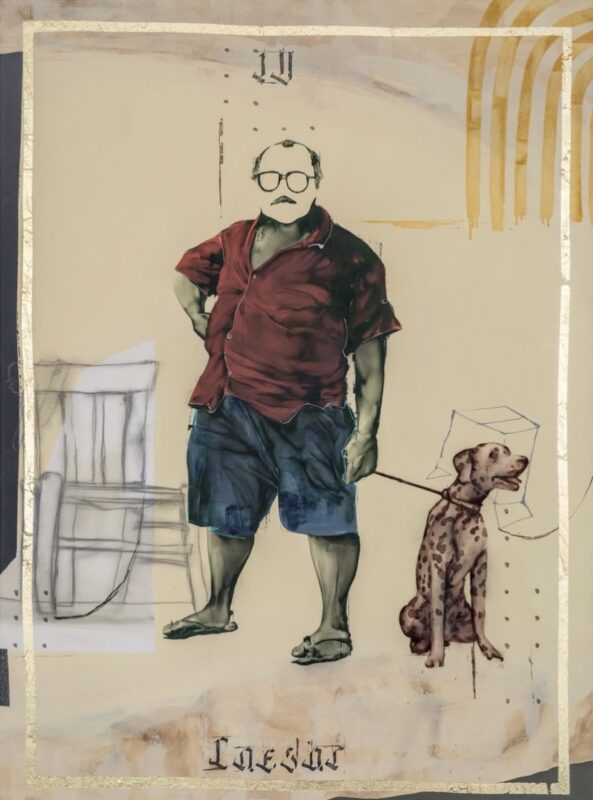

Image:Hugo Wilson

June 25th – August 6th , 2011

“Through a Glass Darkly” curated by Jane Neal featuring Tim Braden, Ciprian Muresan, Daniel Pitin and Hugo Wilson :3143 S. La Cienega Blvd, Unit B Los Angeles, CA 90016 Entrance on Blackwelder www.nicodimgallery.com

“Through a Glass Darkly”. Curated by the British art critic and curator, Jane Neal, the exhibition brings together four of the most dynamic and intriguing young artists working in Europe today: Tim Braden, Daniel Pitin, Ciprian Muresan and

Hugo Wilson.

The title of the show is taken from a verse in the Bible (1 Corinthians 13). It

references the blurry confusion of life in light of the future clarity of heavenly perspective. The phrase also served as the title for Ingmar Bergman’s 1961 film involving four characters, each of whom offers an insight into the mind and actions of the others, thus serving as a kind of ‘mirror’.

Taking place on a bleak Swedish island over an intense, 24 hour period, the film charts the descent into madness of Karin, the main protagonist, and witnesses the often desperate actions of the remaining three characters: Karin’s husband (and psychiatrist), her absentee father and her highly-strung brother. Karin’s obsessive watching of the wallpaper in her room, and her ‘fate’ at the hands of the men in her life has prompted comparisons to be drawn with Charlotte Perkins

Gilman’s chilling short story: The Yellow Wallpaper (first published 1892).

The artists in this exhibition were all aware of both the Biblical verse and the film. The intention behind the show was not to call the artists to respond directly to either verse or film, but for them to have in mind something of the atmosphere or motivation of each. The four artists work in distinctly different ways: Braden in paint, Pitin in paint and film, Muresan in drawings, film and sculpture and Wilson in paint, drawing and sculpture; yet each is concerned with something of the sensibilities outlined above.

Image: Tim Braden inheritance Spaniard

Tim Braden has always interpreted the phrase “through a glass darkly” as referring to both the fog of memory and the haze of experience. For him it is closer to the notion illustrated by the analogy of Plato’s cave (where shadows seem more real than the people). What Baudrillard would later call the simulacra; where objects become more real than their referents. In cinematic terms this is interesting in the case of actors playing famous real life people (as opposed to fictional characters), whose identities they sometimes take over. Braden had been looking at director Peter Watkins’ epic film of the life of Edvard Munch (which coincidentally happened to be one of Bergman’s favourite films). Braden made a portrait of the actress playing Lara, Munch’s sister. The painting is one of a number of works made by Braden where actors stand in for artists (or their friends or family), based on their physical similarity to their painted portrait ‘doppelganger’. Braden ‘borrowed’ Lara Munch to illustrate and act as Karin in Bergman’s film (which Braden himself has not actually seen, though he has experienced a stage version of the film at the Almeida theatre in London). As

he explains, ‘After a while it all starts to become a little ‘foggy”. Yet the layers of representation involved in the depiction of someone playing the role of a person known only from paintings, become more intriguing through these complexities.

Daniel Pitin remembers ‘Through a Glass Darkly’ as a film where the characters are trying to face something hidden and potentially dark. As he says, ‘the struggle of the actors in the film is one we all have at times. Everyone is confronted with unpleasant or unhappy feelings or situations. In the film itself there is kind of melancholy. All the actors have to spend time on the island, and this could be interpreted as a metaphor for artists closed in their studios and facing their memories and life experiences. Something hidden that wants to be discovered and seen, publicly recovered.’ Yet Pitin is wary of interpreting art solely through psychology, finding it boring when art is explained away in a narrative manner as a kind of Freudian theory. For Pitin, art more closely resembles a theatre play where the viewer can participate in the experience; knowing it to be an illusion but one that can fully engage the emotions, summoning fascination, disappointment and the reflection on personal experience. He likes his work to be open to interpretation, close to his and others’ memories, yet mixed up with crime films and documentaries; mise en scenes that draw together the fictional, the virtual and the real. Pitin is particularly interested in crime films because of the role of the detective. For Pitin, the detective is someone who has access to all levels of society while not belonging to any of them. He has the power to subvert the social strata and to unearth secrets, guilt and longings. Of late Pitin has come to realise that when he incorporates imagery from film he is actively seeking to break down and through the ‘still’ in order to deconstruct the space or the image itself. He does this in various ways: sometimes by ripping or burning paper and canvas, sometimes by adding to the surface in order to disrupt it. In Pitin’s words: ‘it is a strange process’. The image is destroyed and forgotten then it re-emerges on the canvas, transformed – with all the marks and history of the journey. It is, says Pitin : ‘As if the motion picture is trying to defend its fixed position on the canvas and so fights with the painter. Once the painter starts the break down the image it is as if it wants to disappear, leaving only a trace of its original essence behind like a

clue in a crime scene.’ This tantalising glimpse of ‘evidence’ is enough to enroll the ‘audience’ in the game of playing detective, prompting them to question what is happening in the work and what has taken place. The situation is heightened by Pitin’s attraction to situations where, he says: ‘you are neither here nor there’. Like the desert, the stage or a boat it is somewhere in the between, in common with Foucault’s heterotopia of the mirror, a strange land beyond knowable boundaries. Recently Pitin has begun to work in film, producing experimental narratives such as ‘Dinner with Malevich’ which obliquely references the creeping influence of dark matter as it infiltrates the heart of a family and spreads beyond into society. A vein of brooding trouble pulses through much of Pitin’s new work with paintings such as “Blue Angel” (inspired by Joseph von Sternberg’s film that

charts the demise of a school teacher after he falls for a dancer) capturing an overwhelming sense of the inevitability of fate.

Ciprian Muresan blends humour with dark and knowing poignancy. His work often involves the translation of literary models into imagery, sometimes into the form of drawings, and at other times into film, or both. Muresan’s researches into commmunist and post communist culture have resulted in classic films and animations adapted and mediated through current popular culture, and sculptural works that cleverly but subtlely engage with a pertinent past or present issue. One of Muresan’s recent sources of inspiration is the Tale of the Troika (?????? ? ??????). A 1968 satirical science fiction novel written by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky, the book pokes fun at both Soviet bureaucracy and over-emphasis on science as a means for the evaluation of almost everything. Although the novel itself was not directed against the state per se – and it is fair to say a number of the points it picks up on also resonate with global bureaucracy today and the field of contemporary scientific research – it was not ‘approved’ under Soviet rule. The Strugatsky brothers’ story sees the world divided into innumerable floors, connected by elevators that are permanently broken down. No one seems to know much about anything above floor thirteen, then one day, two scientists are sent up to the 76th floor, to ‘The Colony of Unexplained Phenomena’. Here they find the Troika, a ruling triumvirate not of three, but of four men, has seized power. The Troika seeks to rationalise away unexplained phenomena – even such

strange things as Gabby the talking bedbug who proposes a new era of peaceful ‘coexistence between man and bug’, or Old Man Edelweiss, the visitor from Outer Space who has 77 parents of 7 distinctly different sexes. In Muresan’s version, the story becomes a series of drawings adapted from the tale. These drawings are in turn subjected to a bizarre ‘scientific experiment’. Muresan ‘arranges’ for them to be run over, so that, we assume, any evidence of ‘unexplained phenomena’ can be removed. In an added twist the artist keeps the remains, literally ‘framing the evidence’: which, though mangled, nevertheless provides a window into a strange and bizarre world.

For Hugo Wilson, the Corinthians passage: ‘Through a Glass Darkly’ is a concept that resonates with much of his work. Wilson feels that the very human need to categorize and explain what is around us; the desire to try and work out ‘the plan’ is particularly fascinating in the context of history. Most especially he is interested in the period when no scientific ‘facts’ were readily available, yet nonetheless, attempts were always made, (often driven by systems of belief) to organize and create hypotheses. Of late, Wilson has been investigating ‘the Doctrine of the Signatures‘ (a philosophy shared by herbalists from the time of Dioscurides (6th Century) that states that herbs which resemble various parts of the body can be used to treat ailments of that body part.

One example is the snakeroot, believed to antidote snake bite, others are lungwort and wormwood which were understood to cure intestinal parasites). As Wilson explains, this philosophy really took hold thanks to the support of theological justification. It was reasoned that God must have set His ‘sign’ upon the cures that He provided. So the common names of many plants whose shapes and colours reminded herbalists of the parts of the body they were believed to heal, have been retained. The concept was developed further by Paracelsus (1491-1541) and published in his writings.

The doctrine of signatures was spread by the writings of Jakob Bohme (1875-1624), who suggested that God marked objects with a sign for their purpose. For Wilson, the theory (which was taken as medical fact for over one hundred years in Europe), is a clear example of how human nature is willing to put ‘blind faith’ in ‘facts’ that might not, in the end provide answers. It prompted the artist to wonder whether modern ‘theories’ or ‘facts’ such as the human genome project will in the end turn out to provide the answers it is believed to contain.

Wilson’s new work involves taking specific examples from the doctrine and placing them into a context of either religious or scientific illustration. Combining the context of 16th Century religious painting with the kind of imagery more usually associated with scientific illustration, Wilson evokes the spirit of 16th Century Catholic painting (when demonstrations and Biblical illustrations often had to be imparted to largely illiterate congregations). Marrying his interest in science past through delicate depictions of Eyebright and Snakeroot with painterly allegory, Wilson has recently configured a homage to Hieronymus Bosch by re-working his allegorical table of the seven deadly sins. Wilson’s version is a table of lunacy. It demonstrates the phases of the lunar cycle and its possible affects on everyday life in terms of fertility, sanity, tidal systems and even alcohol intake. Interestingly, as Wilson observes, in today’s increasingly secular world, people are more likely to trust in the possible effects of the lunar cycle on their lives, than in the will of God. Yet even this suggests an in-built human need to be ‘governed’ by greater forces, as despite contemporary man’s faith in science, the desire to believe we are not entirely responsible for our fate is both a reassuring and seductive one.