Visitors to the Somerset House summer exhibition are invited to inspect the revered world of Masion Martin Margelia. Like the label’s collection the visitors’ impressions are controlled leaving nothing to the imagination. Even the exhibition guide cover is a relatively dense and serious description of the brand, set out like a dictionary definition. The exhibits’ meanings are not up for interpretation; instead the visitor is encouraged to refer to the exhibition guide, whilst examining each of the 30 sections. Although Margiela opted for anonymity – to allow the clothes to speak for themselves – it does make the identity of the founding designer more intriguing; making one enquire further and look harder.

Perhaps visitors could have been given white lab coats to wear and a magnifying glass to use whilst walking around the exhibition – however, this would indicate that the visitor is part of the House and this is certainly not the case.

The impassive tone of the exhibition ensures that visitors are aware they are merely voyeurs to the wonders behind Maison Martin Margiela and not participants. This doesn’t mean the exhibition is mundane. It is the detail that is most inspiring and the cold presentation strangely illuminating – is the Margelia party over or were we never really invited?

In 1989 Martin Margelia showcased his first self-entitled collection after graduating from Antwerp’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts. The rebellious Margiela was often referred to as the seventh member of the Antwerp six, a radical fashion collective tutored by Linda Loppa at the Academy between 1980-1.

His avant-garde designs were intrinsic to the ‘deconstruction’ movement that was ripping the fashion world apart in the late eighties. Margelia wasn’t destroying clothes but instead, as a reaction to the predominantly orthodox fashion world, he was working back into the construction of garments in order to move forward and hence revolutionise the scene.

By literally deconstructing garments Margiela was able to rethink the function of clothing and question our relationships between the body and how we dress it. This conceptual presence, along with other designers at the time, was groundbreaking and is still important today – Note the serious but always present crowd at the exhibition that celebrates 20 years of the innovative label.

The recycling of garments for Margiela is about giving pieces new life and a new history. This idea is epitomised in exhibit ‘13. Assemblage’: a sleeveless fur jacket made from two second-hand jackets sewn together is displayed with a double-sided mirror positioned between the jacket’s lapels so from either side of the mirror you see two separate jackets but from behind one can view the assembled Margiela garment. But, unlike Robin Hood, Margelia doesn’t give to the poor but, instead, makes scrap materials into expensive luxury fashion pieces for the fashion elite to wear

Most fascinating to me is Margiela’s idiosyncratic approach to the fashion show. The quirky and innovative show invitations on display in exhibit ‘4. Invitations’ are enjoyable: Chocolate bars; a wishbone; wristbands and a plate to name a few. Highbrow invitees would then be further surprised by his unconventional shows where one might find themselves balancing on crummy vintage furniture or at a Salvation Army hall drinking out of plastic cups.

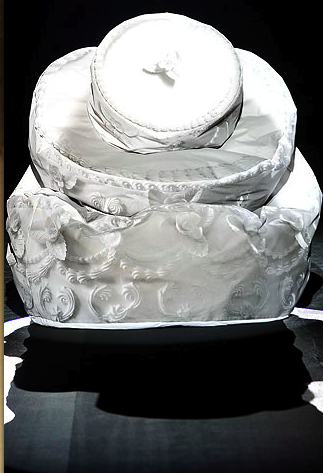

The exhibition is a construction of Margiela’s 20 year journey of deconstructing fashion. If – according to Derrida – deconstruction is only possible when the outcome of deconstruction is already apparent, then the exhibition’s problem lies with this paradox. People get it: inside/outside; recycling; destroy; trompe l’oeil; replicas. So maybe the confetti on the floor in ’23. Birthday Room’ and the deflated birthday cake suggests that the party is over and Margiela ‘may’ have left a while ago.

Exhibition runs until 5th September www.somersethouse.org.uk/

Tory Turk