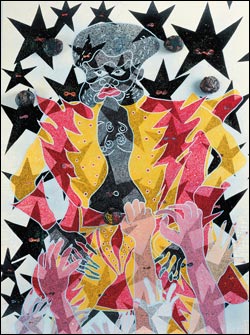

There are few harsher adjectives in the art critic’s lexicon than ’decorative’. There’s a certain kind of art that is so pretty, so beautifully patterned, such fun to look at that an sensible art critic feels duty bound to avert his gaze. The paintings of Chris Ofili, currently displayed in a mindblowing mid-career retrospective at the Tate, are a prima facie example. In most of Chris Ofili’s paintings, thousands of tiny droplets of paint, dispensed from a syringe, trace curving patterns across his canvases. Underneath them the rich and saturated colours of Gauguin’s Tahitian palette mingle with the arabesques of Matisse’s lines (only more sensuously, as if – sorry for racial the steroetyping – Matisse had been black). On top of that cascades of glitter often sparkle. This over-iced cake fuses into idealised images of African men and women, of jungle paradises and of love.

The fun doesn’t stop there. Like a Kung Fu hero who takes on all comers at once. Ofili’s pictures have crowd-pleasing titles like ”Seven Bitches Tossing Their Pussies Before The Divine Dung” (1995) or ”Afro Love and Unity” which seduce the hardcore hip-hop crew and fans of seventies jazz fusion. At the other end of the spectrum, there are curator-crowd-pleasing ploys, like resting the paintings on dung, at a slight angle to the wall, thereby giving art theorists that long-awaited chance to write at length about whether the artist has made paintings or sculptures. It all seems too easy for the 38-year-old painter who won the Turner prize at the tender age of 30 and whose life has become one long Caribbean holiday in his new home in Trinidad.

Apologists for joys of Ofili’s paintings talk about his engagement with issues of gender, race and identity. They cite the diverse African sources in his work – the droplet patterns from ancient paintings at the ruined palaces of the African kingdom of Great Zimbabwe, and the black stereotypes from Tarantino and Blaxploitation films. They draw attention to ”No Woman, No Cry” (1998), which was inspired by the mother of Stephen Lawrence, in which a beautiful woman in profile cries tears through closed eyes. Each tear contains a photo portrait of Stephen Lawrence. It is a supremely moving painting, which moistens the eyes of this cynical art critic every time he sees it. They mention the subversion of the elephant dung, of course. But they’ve got it wrong. There’s nothing radical about using the scatalogical in art nowadays. It’s the decoration, not the dung!

At certain times in art history, and only if employed by the sharpest minds and most skilful hands, decoration can become a weapon. The case study in this is the Austrian art nouveau artist Gustav Klimt, who led the proto-modernist movement of the Viennese Secession. The similarities between Klimt and Ofili are striking. Both careers span the end and beginning of two centuries. The paintings of both artists are flat, highly decorative, utopian in their vision and sexually explicit. Ofili’s paintings of the nineties were full of cut-out details from pornographic magazines. Klimt’s work similarly broke the sexual taboos of his own day with his depiction of a naked woman crouching from behind or simply lovers kissing. Klimt’s subjects are set in a golden Byzantium, Ofili’s often in a verdant jungle. The opulence in the work of both artists appeals to the wealthiest collectors of the day, while shocking the broader establishment. The Viennese authorities accused Klimt of perversion, and Ofili notoriously aroused the fury of New York’s mayor Guiliani with his black Madonna decorated with elephant dung, when Charles Saatchi’s ’Sensation’ exhibition travelled to the Brookyln Museum of Art in 1999. Both artists employed decorative techniques as an avant-garde strategy to escape the clutches of the art dogmas of the day, in Klimt’s case the neo-classicism of salon art, in Ofili’s neo-expressionism and conceptualism.

Yet there are differences between Klimt and Ofili’s decoration too – a difference that exemplifies the differences between our two ages. There was nothing ironic about the fin-de-siecle and Klimt’s Byzantine marble, mosaic and gold. Ofili’s decoration, on the other hand, is an exercise in ambivalence. His paintings have , until very recently, ressembled the cheap screen-printed batiks of Asian and African tourist markets, or San Franciscan psychedelic rock concert posters. His cartoony black men and women come from the Afro-American comic book art of the seventies – just think of the cover of Miles Davis’ album ”On the Corner.” A postmodern man, Ofili mocks his own utopias. Like Warhol or Koons, he sumptuously aestheticises kitsch. And like those artists too Ofili has it both ways. The political messages of Ofili’s paintings are pleasingly ambiguous. Take the famous ”Holy Virgin Mary” from 1996, the one with the famous elephant faeces. A black woman stands surrounded by little cut-out pornographic photos of black female bottoms. The expression on her face could be a look of bemusement or a scowl. So this picture could a condemnation of exploitative images of black women, or a kind of hedonistic celebration of them.

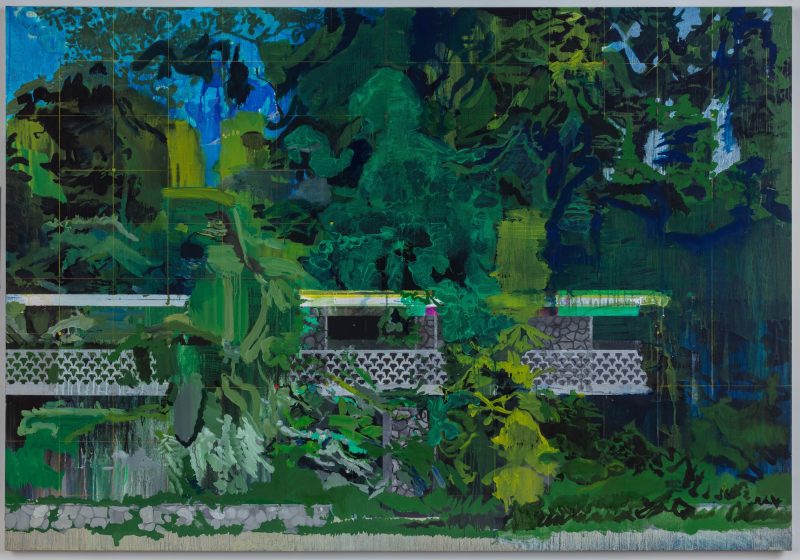

Yet there are limits to the power of the decorative. Klimt’s decorative art did not prove much of a blueprint for the future of modernism, which went in the opposite direction towards the starkness of Constructivism’s geometry and the lurid crudeness of Expressionist’s bathers. He had few heirs – and most of them like Friedensreich Hunderwasser, are derided. Klimt had ended his most decorative phase by 1910, leaving the gold and intricate pattermns behind, and here’s another uncanny parallel with Ofili. His recent work shows a similar change of direction, from the decorative to the beautiful. The dots of pigment and glitter have vanished. A question mark may hang over his latest Beardley-esque latest work in the Tate show’s room, but not over the masterful room of blue paintings. In a series of breathtakingly well-handled colour compositions in dark closely toned hues of blue, purple and black, Ofili captures the palette of a tropical night and depicts imagery from Trinidadian folklore. Here Ofili the painter and decorator is replaced by the Rothko of figuration.

www.tate.org.uk

Pippa Irvine Review :www.fadwebsite.com

Charlotte Higgins at The Guardian:www.guardian.co.uk

Jackie Wullschlager at The FT:www.ft.com

www.benlewis.tv www.artsafari.tv