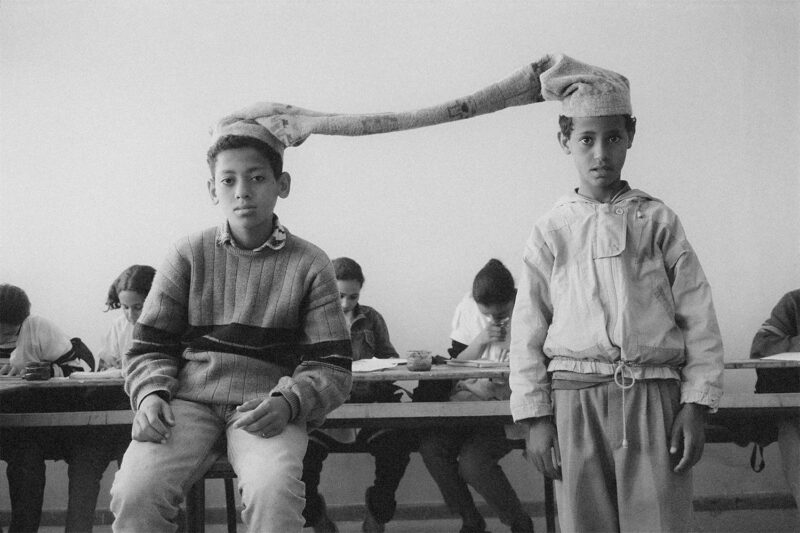

Presented as a celebration of the centenary of the birth of Henri Cartier- Bresson, this exhibition proposes a course starting from the 320 works preserved at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie. This collection was constituted starting from two broad topics: Paris and the Europeans.

The first is the result of a long work undertaken on the files of the photographer. Between 1980 and 1984, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Daniel Arnault, of Magnum, and Jean-Luc Monterosso selected a corpus of images on Paris. This unit then gave place to an exhibition, “Paris at view of the eye”, presented at the Carnavalet Museum during the Month of Photography, in November 1984. For the Europeans, Henri Cartier-Bresson, in echo with the book of the same title, designed and published by Tériade in 1955, revisited, with Maurice Coriat, again his files. Presented to the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in March 1997, the totality of outtakes from this exhibition was the object, on a proposal from Jean-Stanislas Retel, of a gift from the Reader’ s Digest France Foundation.

These photographs illustrate at the same time a style and a practice. They incarnate this perfect moment, transcendent, which mixes emotion and sharp-edged glance.

Henri Cartier-Bresson (August 22, 1908 – August 3, 2004) was a French photographer considered to be the father of modern photojournalism, an early adopter of 35 mm format, and the master of candid photography. He helped develop the “street photography” or “real life reportage” style that has influenced generations of photographers that followed.

Cartier-Bresson studied in Paris at the École Fénelon, a Catholic school. After unsuccessful attempts to learn music, his uncle Louis, a gifted painter, introduced Cartier-Bresson to oil painting. “Painting has been my obsession from the time that my ‘mythical father’, my father’s brother, led me into his studio during the Christmas holidays in 1913, when I was five years old. There I lived in the atmosphere of painting; I inhaled the canvases.”[citation needed] Uncle Louis’ painting lessons were cut short, however, when he died in World War I.

In 1927, at the age of 19, Cartier-Bresson entered a private art school and the Lhote Academy, the Parisian studio of the Cubist painter and sculptor André Lhote. Lhote’s ambition was to unify the Cubists’ approach to reality with classical artistic forms, and to link the French classical tradition of Nicolas Poussin and Jacques-Louis David to Modernism. Cartier-Bresson also studied painting with society portraitist Jacques Émile Blanche. During this period he read Dostoevsky, Schopenhauer, Rimbaud, Nietzsche, Mallarmé, Freud, Proust, Joyce, Hegel, Engels and Marx. Lhote took his pupils to the Louvre to study classical artists and to Parisian galleries to study contemporary art. Cartier-Bresson’s interest in modern art was combined with an admiration for the works of the Renaissance—of masterpieces from Jan van Eyck, Paolo Uccello, Masaccio and Piero della Francesca. Cartier-Bresson often regarded Lhote as his teacher of photography without a camera.

Although Cartier-Bresson gradually began to feel uncomfortable with Lhote’s “rule-laden” approach to art, his rigorous theoretical training would later help him to confront and resolve problems of artistic form and composition in photography. In the 1920s, schools of photographic realism were popping up throughout Europe, but each had a different view on the direction photography should take. The photography revolution had begun: “Crush tradition! Photograph things as they are!” The Surrealist movement (founded in 1924) was a catalyst for this paradigm shift. While still studying at Lhote’s studio, Cartier-Bresson began socializing with the Surrealists at the Café Cyrano, in the Place Blanche. He met a number of the movement’s leading protagonists, and was particularly drawn to the Surrealist movement of linking the subconscious and the immediate to their work.

Cartier-Bresson matured artistically in this stormy cultural and political environment. He was aware of the concepts and theories mentioned but could not find a way of expressing this imaginatively in his paintings. He was very frustrated with his experiments and subsequently destroyed the majority of his early works.

From 1928 to 1929, Cartier-Bresson attended the University of Cambridge studying English art and literature and became bilingual. In 1930, he did his mandatory service in the French Army stationed at Le Bourget, near Paris. He remembered, “And I had quite a hard time of it, too, because I was toting Joyce under my arm and a Lebel rifle on my shoulder.”

In 1931, once out of the Army and after having read Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Cartier-Bresson sought adventure on the Côte d’Ivoire, within French colonial Africa. He wrote, “I left Lhote’s studio because I did not want to enter into that systematic spirit. I wanted to be myself. To paint and to change the world counted for more than everything in my life.” He survived by shooting game and selling it to local villagers. From hunting, he learned methods that he would later use in his photography techniques. It was there on the Côte d’Ivoire that he contracted blackwater fever, which nearly killed him. While still feverish he sent instructions for his own funeral, writing to his grandfather and asking to be buried in Normandie, at the edge of the Eawy forest while Debussy’s String Quartet played. An uncle wrote back, “Your grandfather finds all that too expensive. It would be preferable that you return first.” Although Cartier-Bresson took a portable camera (smaller than a Brownie Box) to Côte d’Ivoire, only seven photographs survived the tropics.

Cartier-Bresson traveled to the United States in 1935 with an invitation to exhibit his work at New York’s Julien Levy Gallery. He shared display space with fellow photographers Walker Evans and Manuel Alvarez Bravo. Carmel Snow of Harper’s Bazaar, gave him a fashion assignment, but he fared poorly since he had no idea how to direct or interact with the models. Nevertheless, Snow was the first American editor to publish Cartier-Bresson’s photographs in a magazine. While in New York, he met photographer Paul Strand, who did camerawork for the Depression-era documentary The Plow That Broke the Plains. When he returned to France, Cartier-Bresson applied for a job with renowned French film director Jean Renoir. He acted in Renoir’s 1936 film Partie de campagne and in the 1939 La Règle du jeu, for which he played a butler and served as second assistant. Renoir made Cartier-Bresson act so he could understand how it felt to be on the other side of the camera. Cartier-Bresson also helped Renoir make a film for the Communist party on the 200 families, including his own, who ran France. During the Spanish civil war, Cartier-Bresson co-directed an anti-fascist film with Herbert Kline, to promote the Republican medical services.

Cartier-Bresson’s first photojournalist photos to be published came in 1937 when he covered the coronation of King George VI, for the French weekly Regards. He focused on the new monarch’s adoring subjects lining the London streets, and took no pictures of the king. His photo credit read “Cartier,” as he was hesitant to use his full family name.

In 1937, Cartier-Bresson married a Javanese dancer, Ratna Mohini. They lived in a fourth-floor servants’ flat at 19, rue Danielle Casanova, a large studio with a small bedroom, kitchen and bathroom where Cartier-Bresson developed film. Between 1937 and 1939 Cartier-Bresson worked as a photographer for the French Communists’ evening paper, Ce Soir. With Chim and Capa, Cartier-Bresson was a leftist, but he did not join the French Communist party. He joined the French Army as a Corporal in the Film and Photo unit when World War II broke out in September 1939. During the Battle of France, in June 1940 at St. Dié in the Vosges Mountains, he was captured by German soldiers and spent 35 months in prisoner-of-war camps doing forced labor under the Nazis. As Cartier-Bresson put it, he was forced to perform “thirty-two different kinds of hard manual labor.” He worked “as slowly and as poorly as possible.” He twice tried and failed to escape from the prison camp, and was punished by solitary confinement. His third escape was successful and he hid on a farm in Touraine before getting false papers that allowed him to travel in France. In France, he worked for the underground, aiding other escapees and working secretly with other photographers to cover the Occupation and then the Liberation of France. In 1943, he dug up his beloved Leica camera, which he had buried in farmland near Vosges. At the end of the war he was asked by the American Office of War Information to make a documentary, Le Retour (The Return) about returning French prisoners and displaced persons.

Toward the end of the War, rumors had reached America that Cartier-Bresson had been killed. His film on returning war refugees (released in the United States in 1947) spurred a retrospective of his work at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) instead of the posthumous show that MoMA had been preparing. The show debuted in 1947 together with the publication of his first book, The Photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson. Lincoln Kirstein and Beaumont Newhall wrote the book’s text

In spring 1947, Cartier-Bresson, with Robert Capa, David Seymour, and George Rodger founded Magnum Photos. Capa’s brainchild, Magnum was a cooperative picture agency owned by its members. The team split photo assignments among the members. Rodger, who had quit Life in London after covering World War II, would cover Africa and the Middle East. Chim, who spoke most European languages, would work in Europe. Cartier-Bresson would be assigned to India and China. Vandivert, who had also left Life, would work in America, and Capa would work anywhere that had an assignment. Maria Eisner managed the Paris office and Rita Vandivert, Vandivert’s wife, managed the New York office and became Magnum’s first president.

Magnum’s mission was to “feel the pulse” of the times and some of its first projects were People Live Everywhere, Youth of the World, Women of the World and The Child Generation. Magnum aimed to use photography in the service of humanity, and provided arresting, widely viewed images.

Cartier-Bresson achieved international recognition for his coverage of Gandhi’s funeral in India in 1948 and the last (1949) stage of the Chinese Civil War. He covered the last six months of the Kuomintang administration and the first six months of the Maoist People’s Republic. He also photographed the last surviving Imperial eunuchs in Beijing, as the city was falling to the communists. From China, he went on to Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), where he documented the gaining of independence from the Dutch.

In 1952, Cartier-Bresson published his book Images à la sauvette, whose English edition was titled The Decisive Moment. It included a portfolio of 126 of his photos from the East and the West. The book’s cover was drawn by Henri Matisse. For his 4,500-word philosophical preface, Cartier-Bresson took his keynote text from the 17th century Cardinal de Retz: “Il n’y a rien dans ce monde qui n’ait un moment decisif” (“There is nothing in this world that does not have a decisive moment”). Cartier-Bresson applied this to his photographic style. He said: ” “Photographier: c’est dans un même instant et en une fraction de seconde reconnaître un fait et l’organisation rigoureuse de formes perçues visuellement qui expriment et signifient ce fait.”

Both titles came from publishers. Tériade, the Greek-born French publisher whom Cartier-Bresson idolized, gave the book its French title, Images à la Sauvette, which can loosely be translated as “images on the run” or “stolen images.” Dick Simon of Simon & Schuster came up with the English title The Decisive Moment. Margot Shore, Magnum’s Paris bureau chief, did the English translation of Cartier-Bresson’s French preface.

“Photography is not like painting,” Cartier-Bresson told the Washington Post in 1957. “There is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera. That is the moment the photographer is creative,” he said. “Oop! The Moment! Once you miss it, it is gone forever.”

Cartier-Bresson held his first exhibition in France at the Pavillon de Marsan in the Louvre in 1955.

Cartier-Bresson’s photography took him to many places on the globe – China, Mexico, Canada, the United States, India, Japan, Soviet Union and many other countries. He became the first Western photographer to photograph “freely” in the post-war Soviet Union. In 1968, he began to turn away from photography and return to his passion for drawing and painting. Cartier-Bresson withdrew as a principal of Magnum (which still distributed his photographs) in 1966 to concentrate on portraiture and landscapes. In 1967, he was divorced from his first wife, Ratna “Elie”. He married photographer Martine Franck, thirty years younger than himself, in 1970. The couple had a daughter, Mélanie, in May 1972.

Cartier-Bresson retired from photography in the early 1970s and by 1975 no longer took pictures other than an occasional private portrait; he said he kept his camera in a safe at his house and rarely took it out. He returned to drawing and painting. After a lifetime of developing his artistic vision through photography, he said, “All I care about these days is painting — photography has never been more than a way into painting, a sort of instant drawing.” He held his first exhibition of drawings at the Carlton Gallery in New York in 1975.

The Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation was created by Cartier-Bresson, his wife and daughter in 2003, to preserve and shar