Most artists have admired a Matisse in their time. But sculptor Nick Hornby has quoted the master in three dimensions and produced a large fantasia in polished walnut that cites an African mask found in the French painter’s oeuvre. It could be one of the largest and most lavish art historical homages you will come across. But to use a favourite expression of Hornby this is a ‘cooked’ take on Matisse, which becomes fully abstract as you walk around it. Such cooked tributes can be found throughout Hornby’s work, as the thirtysomething Slade graduate walks a thin line between critical distance and knowing fandom. The following interview took place over Skype, while Hornby was in New York, where the aforementioned Matisse piece has already sold, in a group show at Paul Kasmin Gallery.

13 curators chose 13 artists for the show at Paul Kasmin. What was the aim for you and curator Thomas Rom?

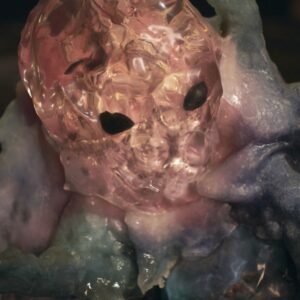

It’s a mix of curators. It has people like John Richardson, the Picasso biographer through to Phong Bui, co-founder of The Brooklyn Rail. I’ve been working on a new body of sculpture, derived from Matisse’s cutouts, which I was really eager to realize in wood. I try to look at the whole range of modes of fabrication from doing it myself through to very high-end production. With this Matisse series, each piece is extruded into 3d and then mirrored – so from the side you have a perfect quotation but from the front you have this very symmetrical image which looks uncannily like an African mask. I needed to fabricate this piece digitally to keep the Matisse cutout citationally accurate. For this show, through the support of Kasmin, I was able to work with the Walla Walla Foundry in Washington State, who produce elaborate and complex sculptures by Jeff Koons, Paul McCarthy, Urs Fischer, carved directly in wood. It was a great opportunity to realise a piece, which needed real precision in order to work.

Walnut is a luxury commodity. How do you deal with the awareness that your latest piece should at some point enter the market and perhaps not be seen for a while?

I find the luxury realm as interesting as the grassroots scene and the critical agenda, especially within the context of the history of art and sculpture. The history of patronage and collection is extraordinary isn’t it? Your question raises many issues. The 20th Century made a successful critique of the art object… but I tend to be more interested in making work that isn’t fleeting. I tend to want to make art that could be made today, could be made 10 years ago, 200 years ago or 400 years time and something which could still stand up in the future. Both metaphorically and literally. Not least because I think it can be quite obnoxious when artists don’t take responsibility. If I’m setting something in a material that will have longevity, I’m taking responsibility for my current position. I might regret it in the future and think, Oh God, this awful lump of metal is out here. But I think that politically it’s more important to take a position, than to make something in cardboard that is pinned to the wall and can be thrown in the bin. And then, I love materials; that’s why I’m a sculptor. Materials are amazing, so I’m not going to shy away from them. If you carve something in polystyrene it will be wobbly, which can be great. If you carve something in walnut it will remain true, it’s a hard material.

Given the hi tech process of composition which you employ why don’t you 3D print?

I do, but from a very practical perspective for maquettes. I use a full artillery of production methods available and each one has very different nuances. 3D printing is an additive process for building layer upon layer, and if I was making a sculpture where I was trying to bring together 450,000 different references all cooked into one thing, maybe 3D printing would be the perfect solution. At the moment I’m dealing with cut outs and as a result I use a cutting process: laser or water-jet, or a hotwire or whatever it might be. This piece at Kasmin was binary and digital. With my cast pieces – there are many steps which each can produce subjectivity. What I mean… if you make a mould, which has rubber and fiberglass both of which can flex, then take a cast from that mould in a material which distorts as it changes temperature, every single one of those steps produces layers of inaccuracy which have to be eradicated through human hand. I’m very aware of the spectrum between more objective and more subjective, or digital and analogue. Designing on the computer is a Boolean Operation (which is a very precise calculation) and the cutting might be digital. But in between those things there are all sorts of bits of slippage if I’m choosing my outline and I’m using spline curves. You can’t convert an image into a line without subjectivity; ultimately I have to choose where the apex of a lip is going to be, if I’m dealing with a face. Or Brancusi, with Bird in Space, he made a lot of them. I have a ridiculous CAD page with about 40 different birds in space I have traced and overlapped all of them, trying to find which one was the Platonic version, the Platonic Brancusi which was also the Platonic object!

What would Brancusi make of that, you have to wonder

If he had suffered the 20th century and had the neuroses on his shoulder (the crisis of personal subjective and the issues around the postmodern) then I’m sure he wouldn’t feel comfortable in his studio saying, I’m a genius and I’ve got some ideas and I’m going to make them because I’m an author. I don’t think he could do that. In the same way that, if you gave me a blank canvas, and said, “Be an artist,” I would giggle because I’d find the whole thing completely absurd. Now days, Its impossible to not be emotionally distanced from the idea of creativity and authorship.

Is turning to the past a postmodern strategy? What makes you quote Matisse, say?

I hope that all of my work balances distance with complete earnestness which is problematic and gets me in trouble. I love art history. Give me an eight hour aeroplane journey and I will happily, quickly, reread Gombrich. It makes me happy; it’s like a big bowl of macaroni cheese. Obviously I don’t think the history of the world is men on horses. But at the same time I think that Picasso was good. Very good. I am really, genuinely, torn. I think that this idea of the western-centric art historical narrative is absurd, but at the same time it’s a pretty cool story. It’s fun and I do think that Demoiselles D’Avignon is amazing. I mean it’s a completely gobsmacking thing to have done. So I’m not postmodern, because the postmodernists had a comfortable relationship with their ironic distance from things and I come back to a place where I think it’s much more complex than that.

Given that your Glyndebourne show looked back at five centuries of sculpture, two questions: why did you stop in 1504? Do you have a favourite period of sculpture?

I have a plan to do more, I just haven’t done it all yet. I’ve barely scratched the surface. Sculpture is so slow; it takes six months to make something… an original, a mould a cast. You might say, “Nick, just do it in drawing or do it in animation or video”. But I need to make stuff because you can’t really scrutinise the phenomenological experience of a thing until it’s in front of me and I have to deal with the relationship between what it feels like and what it thinks like. Why did I only go back to Michelangelo? Because I had limited time and resources. But also because that’s why I make sculpture. Because aged 16, I went with my art history teacher to Florence and I saw the rough Pietà and that changed my world. So it sticks in my head – there are more interesting references out there, probably, but they’re not in my autobiography yet.

Nick Hornby can be seen in The Curators’ Eggs at Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, until August 18 2017