Arriving in Venice for the vernissage days whilst elections were in full swing, I was surprised to be confronted by a politically charged Biennale. Colonialism, Capitalism, Socialism, contemporary slavery and migration were some of the themes running through the 56th Edition of La Biennale di Venezia, which opened not long after a period of several weeks during which more than 1,800 migrants – many of them African – drowned whilst attempting to flee across the Mediterranean to Europe from dictatorships, poverty or conflict in countries including; Libya, Syria, Somalia and Eritrea. Quite fitting then that this year’s Venice Biennale was curated for the first time in its history by an African – Nigerian Okwui Enwezor. Enwezor has used the opportunity of curating this stalwart of the international art world, to invite artists whose practice examines the world around us, and provide a global platform for some of the most talented contemporary African artists.

Titled “All The World’s Futures”, the 2015 Venice Biennale is a brave and relevant exposition, featuring artists from all corners of the globe, many of them addressing pressing global issues. This year’s offering already has its detractors, including several art critics who have found the political content hard to stomach. However, I agree wholeheartedly with the international Jury; comprised of Naomi Beckwith (USA), Sabine Breitwieser (Austria), Mario Codognato (Italy), Ranjit Hoskote (India), Yongwoo Lee (South Korea), who put out a statement saying they wished to “acknowledge an outstanding Biennale Arte 2015 with an increased number of National participations and a particular sensitivity to current geopolitical urgencies.”

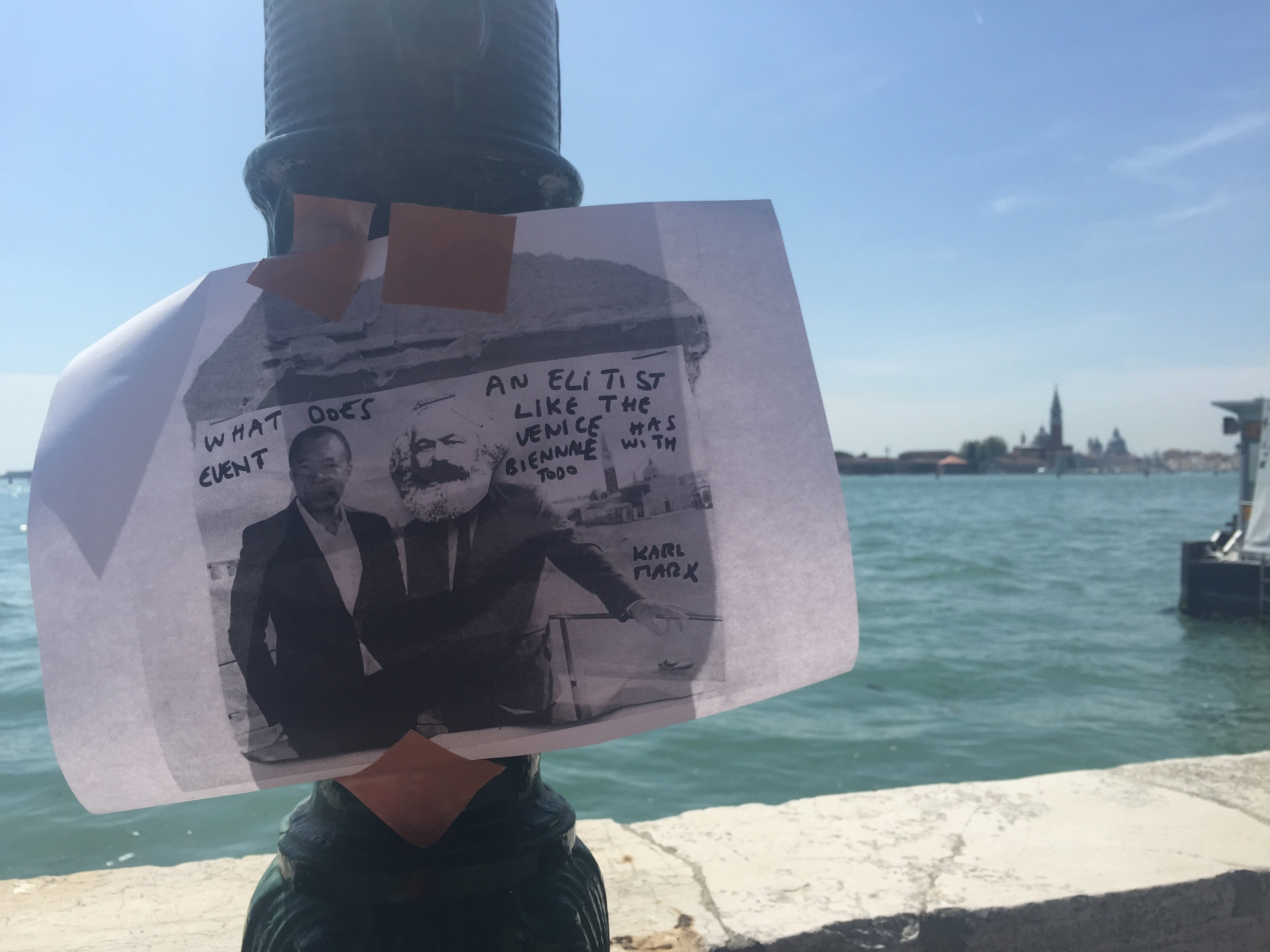

Since the Biennale vernissage is enjoyed mainly by an elitist group of rich, privileged, Prada-clad international art collectors and curators who are granted a first look at the exhibition, there have been accusations by some media that the politicised nature of this year’s Biennale is hypocritical. I’m of the opinion that it’s actually a perfect time for artists to use the world stage of the most respected and long-standing international art exhibition, to address some urgent issues of world politics: In particular migration which is the subject of Vik Muniz’s “Lampedusa” (Pace Gallery), a fragile paper boat floats around the Venetian canals, printed with headlines about migrants who died at sea in recent months after attempting to make the treacherous journey from Libya to Lampedusa in Italy.

My first stop at the Giardini was the British Pavilion, where Sarah Lucas has been given the honour of representing Great Britain. Lucas’s “I Scream Daddio” exhibition consists of sickly custard-coloured yellow walls filled with giant yellow phalluses, collages of Page 3 boobs and sculptures of torsos with cigarettes stuck in their orifices. Whilst artists from countries such as Belgium, Israel and Luxembourg have utilised the opportunity of exhibiting on a world stage to create installations addressing historical and contemporary geopolitical issues, Lucas has filled the British Pavilion with boobs and bottoms, which feels like a wasted opportunity to join in with the international conversation going on in the Biennale about the state of the world. Unless it’s supposed to be so ironic that it’s post-ironic, and her intention was to stay firmly out of any political debate.

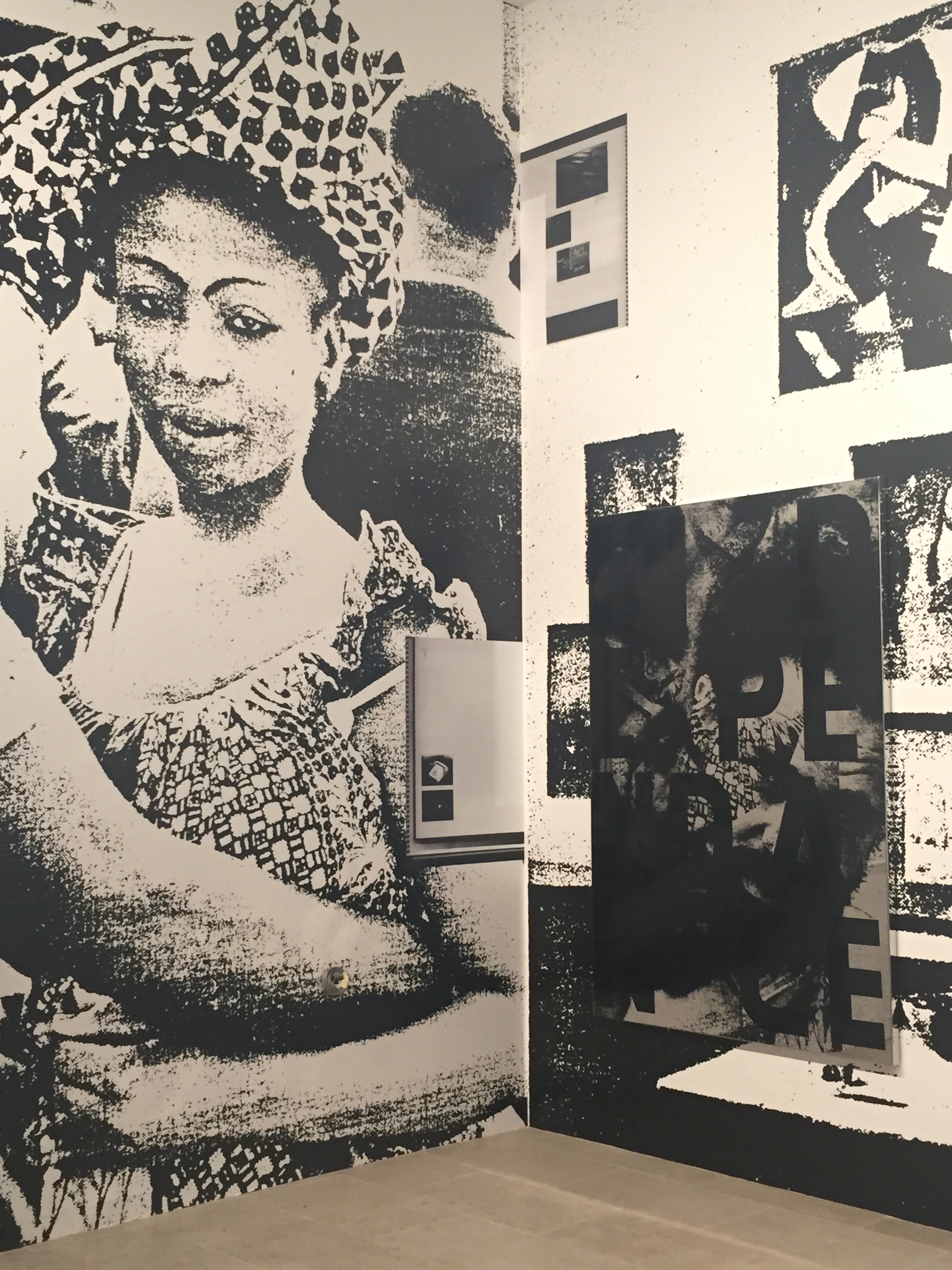

At the Belgian Pavilion Katerina Gregos has curated “Personne et Les Autres”, a thought-provoking exhibition which breaks away from Biennale tradition with Belgian artist Vincent Meessen inviting guests artists of other nationalities including Africa, to comment on the colonialism of his country’s history. At the entrance to the Pavilion a flag by artist Adam Pendleton is emblazoned with the words “Black Lives Matter”, and inside he has covered the walls of one room with his ‘Black Dada’ series of paintings, and his “INDEPENDENCE” series, referencing African American political and cultural movements from the 1960s to the present day. The Belgian Pavilion was built during the reign of King Leopold II, a year before Congo Free State was handed over to the Belgian State. Elisabetta Benassi’s installation “M’Fumu” is constructed from casts of the bones of exotic animals, and is a tribute to Paul Panda (M’Fumu) Farnana, a Congolese activist and intellectual. An actor reads from Mark Twain’s “King Leopold’s Soliloquy” (1905), in a comment on Belgium’s Colonial history.

Since the Venice Biennale has its first curator of African descent, it seems fitting that he uses the opportunity to include a healthy number of African artists in “All the World’s Futures”, both at the former shipyards that constitute the Arsenale, and the central Pavilion of the Giardini. Artists from close to 90 countries are exhibiting in the 56th edition of la Biennale di Venezia, not to mention countless collateral and fringe events all over the city.

There are some interesting national pavilions outside of the Giardini including the Luxembourg Pavilion, which has been transformed into “Paradiso Lussemburgo” by artist Filip Markiewicz. The title of the exhibition is taken from Dante’s Paradiso, as a metaphor for Luxembourg as a fiscal paradise. Visitors are invited to take part in the artwork, and some people took that literally on the evening of the private view when guests charged up with Prosecco from the pop up bar outside, danced manically to a DJ and Bongo player on a dance floor. In the room next door a giddy lady picked up bundles of fake money covering the floor and threw it into the air, laughing drunkenly. Ironically when I examined the money the artist had printed the word “Sorry” in capital letters on each note. But like so many of the privileged visitors who see the Biennale during the Vernissage days and treat it like a society event, she was totally missing the point. The installation included beautifully rendered drawings of contemporary mythology, including one of the world leaders fronting the “Je Suis Charlie” solidarity march after the terrorist attack: a wry comment on the hypocrisy of a demonstration which featured world leaders from countries with well-documented human rights injustices and infringements of freedom of speech: Jordan, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia to name a few.

Near the Luxembourg Pavilion at A Plus A Gallery, an international group of artists took part in “Rob Pruitt’s Flea Market”, an exhibition curated by the School for Curatorial Studies in Venice, which represented a meeting point between art and commerce. Artist James Ostrer transformed himself into “Guru Jimmy”, and sold car bumper stickers with slogans such as “Spirituality is Very Expensive”, in a comment on capitalism and the art world.

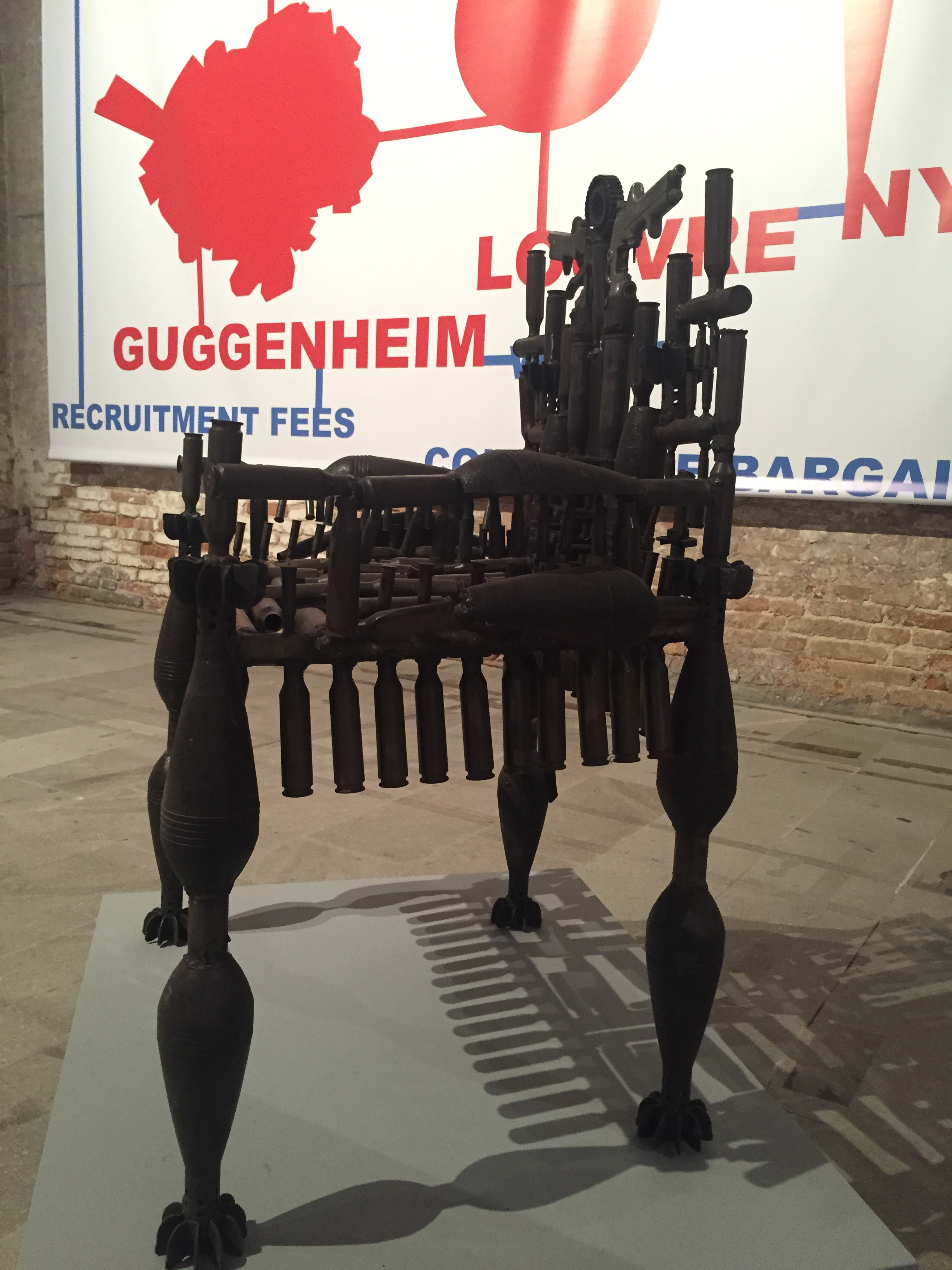

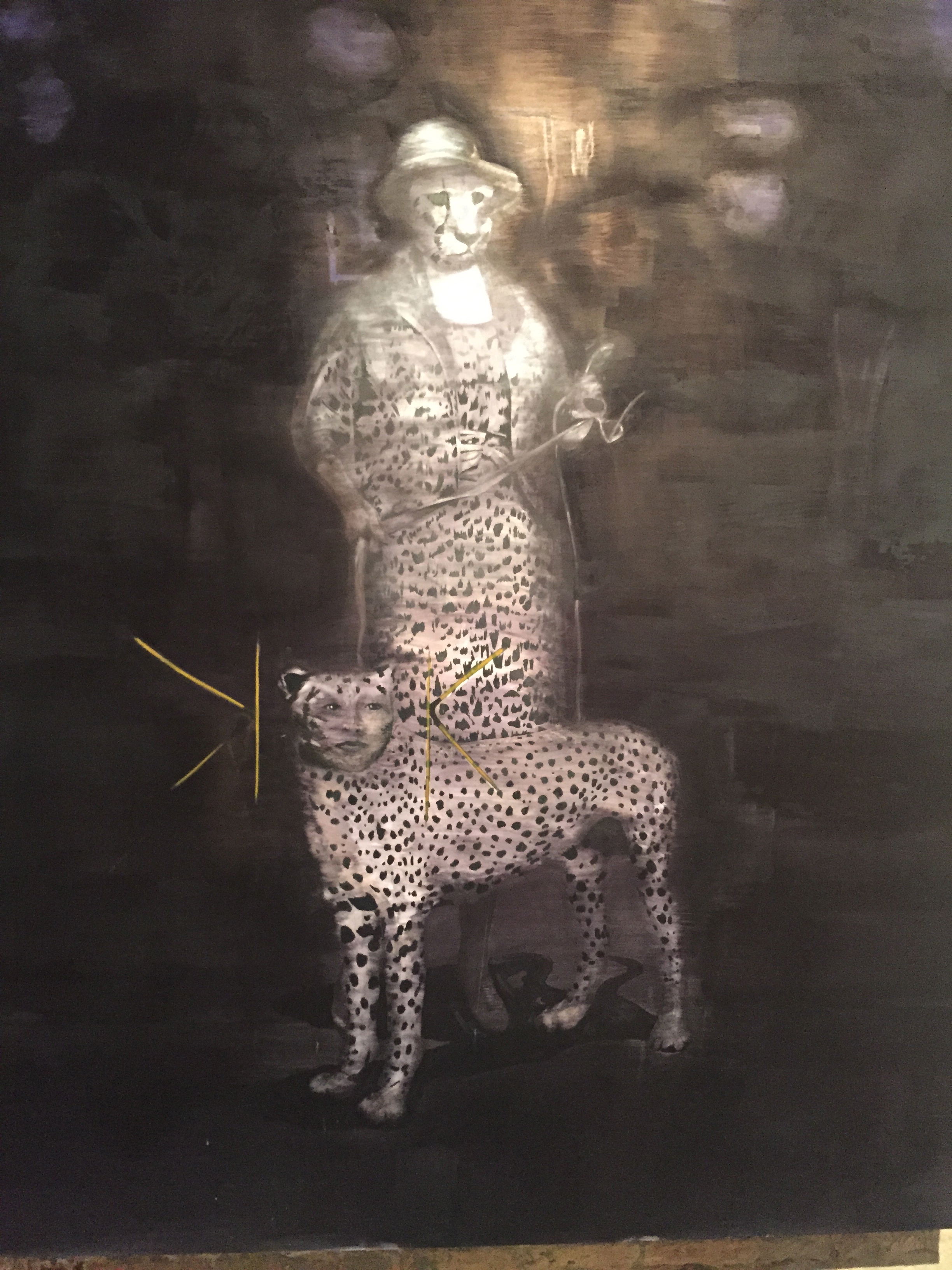

At the Arsenale, the venue of the main “All The World’s Futures” exhibition, polemic artwork includes a giant poster by the Gulf Labor Coalition titled “Who is Building the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi”, a comment on the accusations of Slave Labour in the Gulf, experienced by workers constructing UAE’s cultural hub. This thought-provoking banner is juxtaposed by Mozambique artist Goncalo Mabunda’s Thrones, created from decommissioned weapons titled “The Throne That Never Stops in Time”. This leads thoughtfully to a room with one of very few paintings at the Biennale – an eery image of a safari-hat wearing figure with a feline face, holding a leopard with a human face on a leash, perhaps a comment on colonialism and slavery.

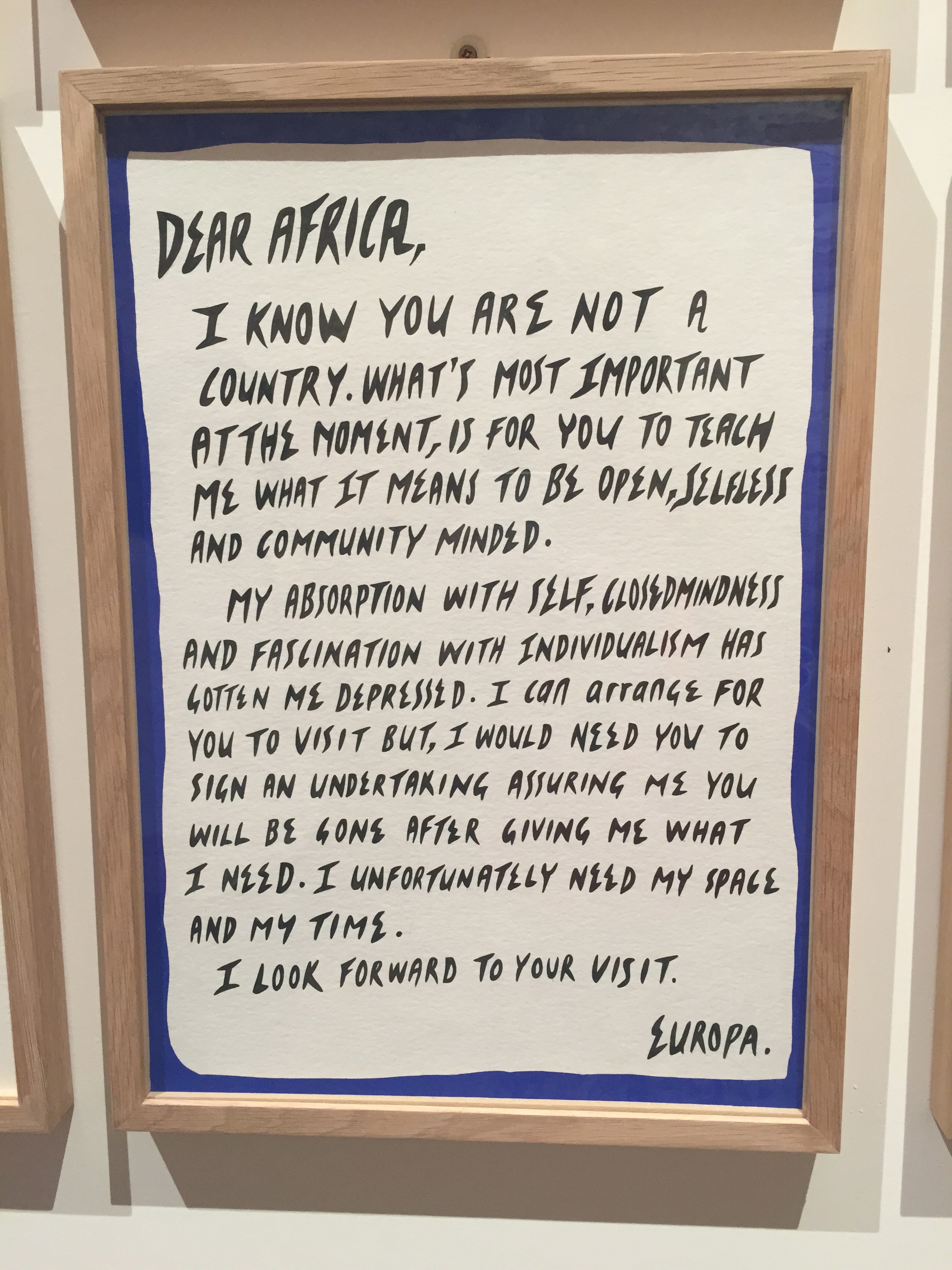

Nearby, a suite of 50 drawings by Nigerian artist Karo Akpokiere comment on the tense and one-way relationship between Africa and Europe, and include an open letter to Africa from Europe which deserves to be repeated in full: “Dear Africa, I know you are not a country. What’s most important at the moment, is for you to teach me what it means to be open, selfless and community minded. My absorption with self, closed-mindness and fascination with individualism has gotten me depressed. I can arrange for you to visit but, I would need you to sign an undertaking assuring me you will be gone after giving me what I need. I unfortunately need my space and my time. I look forward to your visit”, signed ‘Europa’.

African contemporary art is having a moment, and African artists were also represented in other parts of Venice, including “Italia Docet/ Laboratorium” a collateral event at the Palazzo Barbarigo Minotto, co-curated by Anshu Bahanda of Aabru Art and featuring several of the Nigerian artists that exhibited in Aabru Art’s “Transcending Boundaries 2015” recently at Lacey Contemporary Gallery in London.

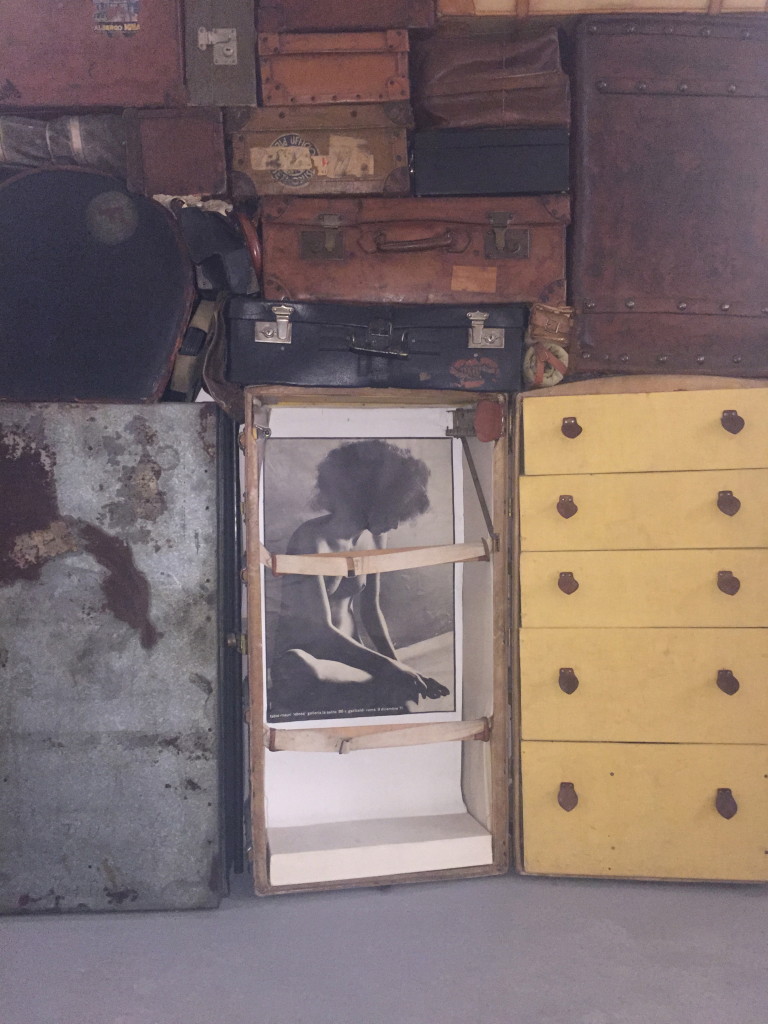

As you leave the Arsenale you can take an exit route through a site-specific installation ‘Out of Bounds’ by Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama. A labour intensive stretch of Venetian thoroughfare is shrouded from top to bottom with used coal sacks, roughly stitched together with different coloured cottons, giving the slightly claustrophobic effect of a military environment, a comment on refugee camps inhabited by stateless migrants.

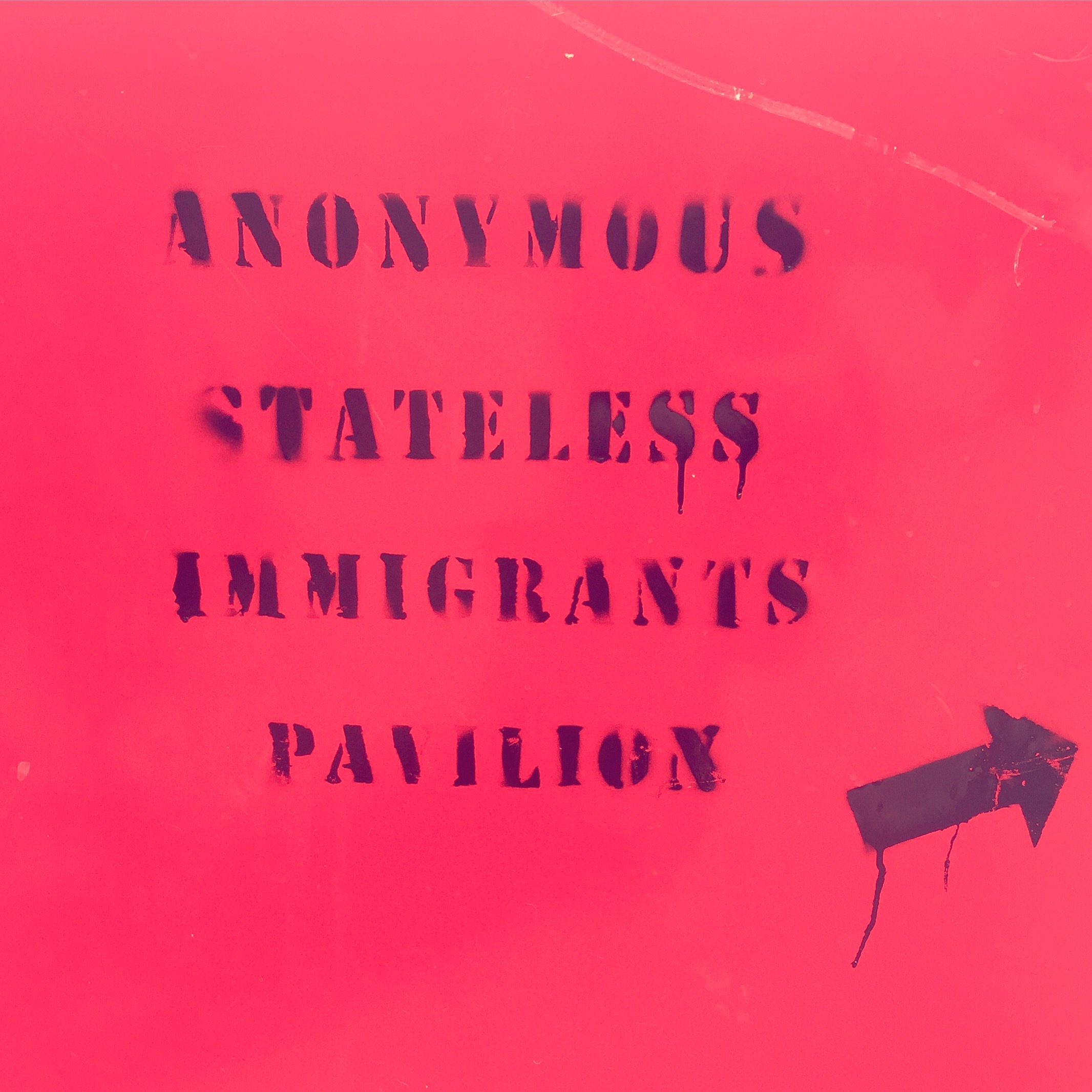

There were some interesting unofficial fringe events around the Giardini that got into the spirit of the political theme. After passing a motionless woman dress in a fluorescent yellow Burqa – “Outsider Pavillion” performance art conceived by Marco Biagini – I stumbled upon the “Anonymous Stateless Immigrants Pavilion” whilst en route to the Arsenale. At the entrance of a park, a woman chalked numbers onto the pavement, representing the migrants who have died in boat disasters whilst attempting to cross the Mediterranean.

A Monk-like figure stood in meditation behind the gates of the park, perhaps contemplating the tragedy of the number of lives lost on these fatal sea-crossings, and a human spider-woman (performance artist Dorothea Seror www.dorotheaseror.de) weaved a web in a tree. Then a naked lady covered in white paint, her face obscured with a rabbit mask, walked calmly towards a small tent, which had the words ‘This is my home’ pinned onto the entrance. Perhaps a comment on refugee camps created by people fleeing war zones in countries such as Syria, a twist on Lewis Carroll’s white rabbit in Alice in Wonderland representing a portal from one world into another, from Africa to Europe.

Close to the Giardini entrance I encountered a young girl in an electric chair, a shocking image conceived by Italian artist Matteo Peretti’s Samarcanda Project (www.samarcandaproject.org) The project takes its name from the city on the Old Silk Road that was a meeting point for different cultures, a commercial route between Asia and Europe. The performance titled “Presumption of Innocence” is a comment on the notion of being born guilty, and alludes to countries with the death penalty where certain races might be presumed guilty without having a chance to prove their innocence.

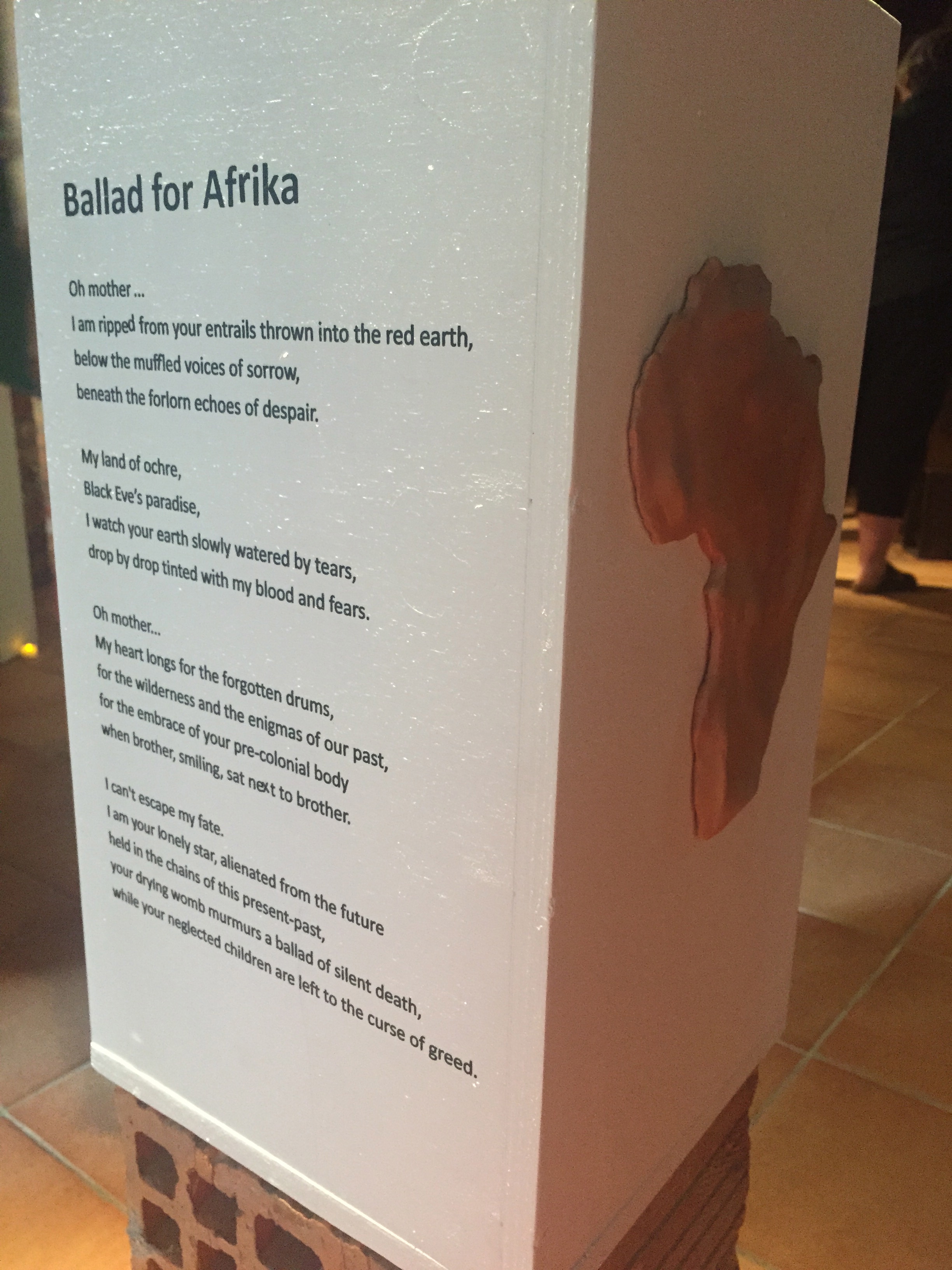

Even in the fringe shows artists were getting on board with the theme of colonialism, including an artist in group show “The Fall of the Rebel Angels” whose “Ballad for Afrika” features a poem lamenting it’s fate: “I can’t escape my fate. I am your lonely star, alienated from the future, held in the chains of the present-past, your drying womb murmurs a ballad of silent death, while your neglected children are left to the curse of greed”. The exhibition at Castello 1610/A on Riva Dei Sette Martiri is well worth a visit, curated by Vanya Balogh it features an eclectic group of artists including Toni Gallagher, Michael Petry and Gavin Turk.

Artnet’s Benjamin Genocchio claimed that the “Okwui Enwezor’s 56th Venice Biennale is morose, joyless and ugly”. It’s true that much of the work in the exhibition makes the viewer uneasy, and forces us to think about issues that are often swept under the carpet. Yet war, politics and injustices done by mankind to their own species are the subjects of some of the most iconic art created in history: Picasso’s “Guernica” and Goya’s “Disasters of War” are just 2 prime examples.

For that is the power of great art, and great artists: it can instigate fundamental debates about humanity and the world we live in. Great art can be about sunflowers and hay Wain’s, but with the current unrest in the world it would be foolish to think that sort of art could make a difference. Whereas Enwezor’s Venice Biennale just might make a few people stop and think about the state of the world, and what we can do to improve international relations and human rights. Artist Glenn Ligon commented on this in a debate with presenter Mariella Frostrup on Radio 4 this week. He had just returned from Venice Biennale and noticed the debate, saying: “Artists are citizens, and the job of citizens is to question what goes on around us. The Biennale is a tough show dealing with what’s going on in the world. For some people that’s a problem, as they think art should be all about spectacle and entertainment. What does it mean to be a citizen? How do we process the world through art objects?” Important questions that many artists featured in the 56th Venice Biennale are attempting to answer.

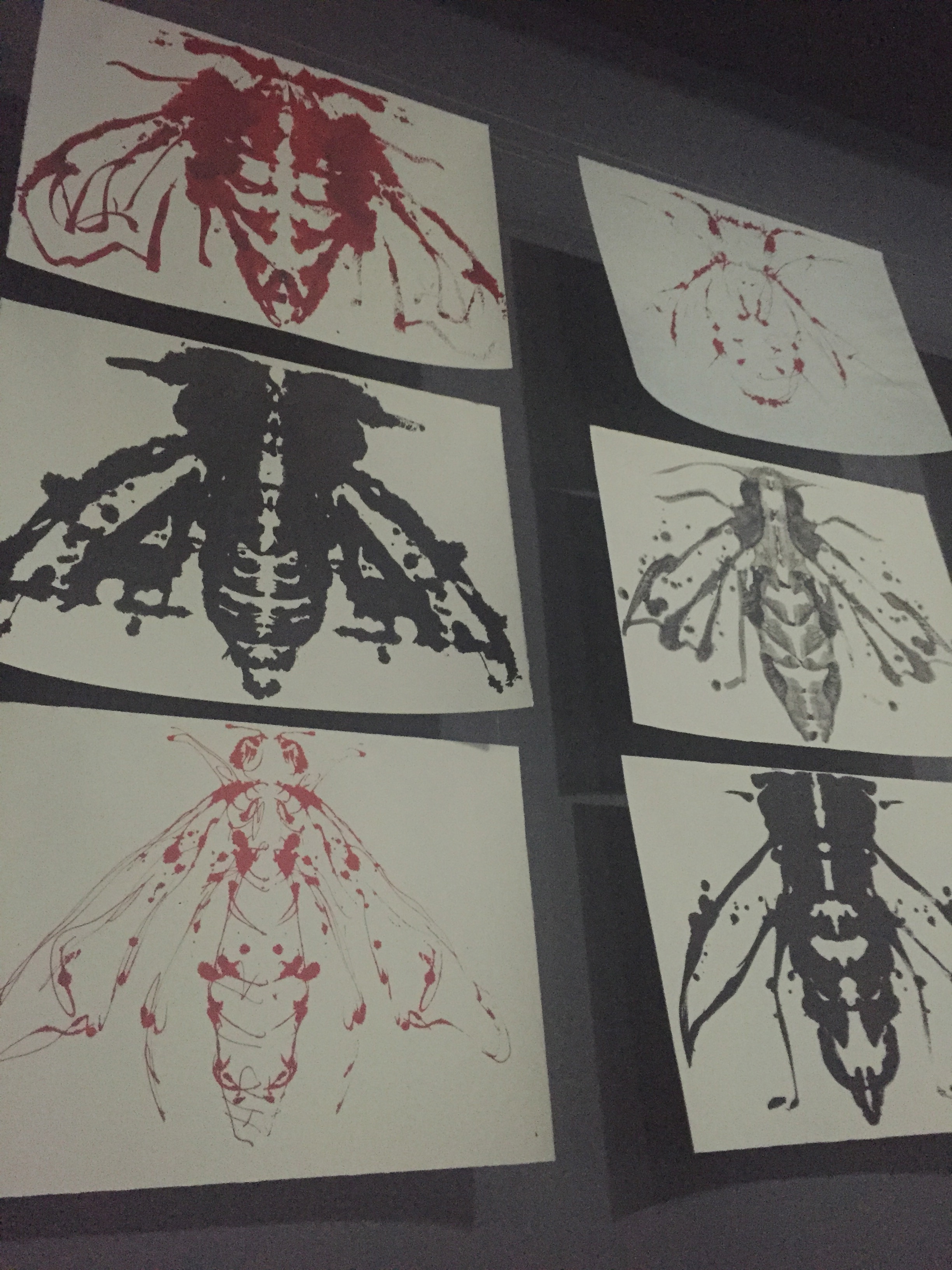

However, the Biennale wasn’t all about making the viewer take a long hard look at some of the injustices of the world around them, there was also a good rejuvenating dose of nature. A lot of video and sound art was evident in the Giardini and the Arsenale, much of it harnessing the meditative and restorative powers of nature. A standout Pavilion for me was the USA who selected Joan Jonas, who at 79 is a veteran art world star. Her immersive installation “They Come to Us Without a Word” takes the visitor on a journey into another world, and was quite rightly given a special mention by the Venice Biennale Jury. Each room of the US Pavilion is inspired by nature, the first room dedicated to bees, the second to fish, and features exquisite drawings juxtaposed with bespoke video art and found objects. Ghostly narration brings an other worldly feel to the films, featuring children and pre-Raphaelite women performing against landscapes from Jonas’s orbit.

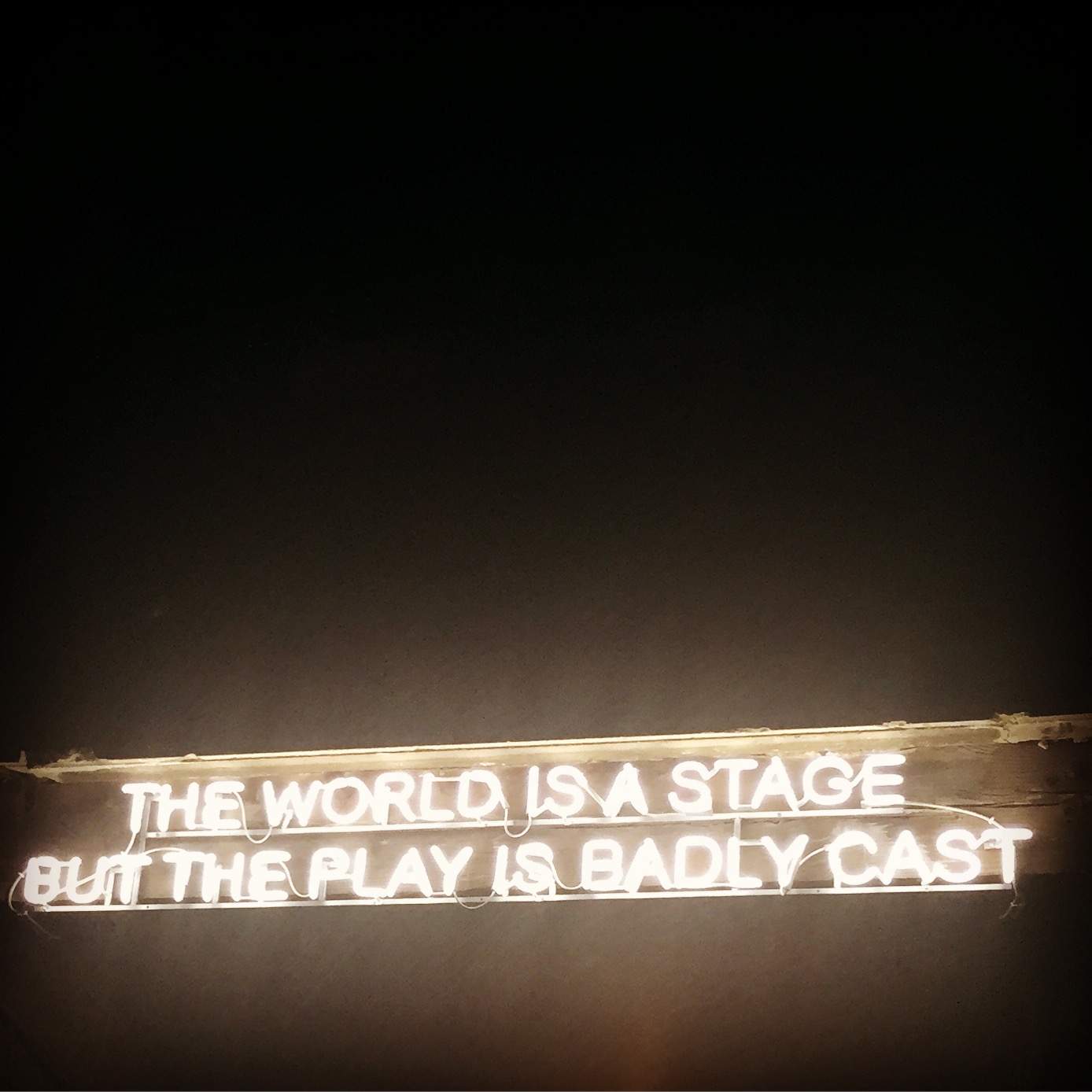

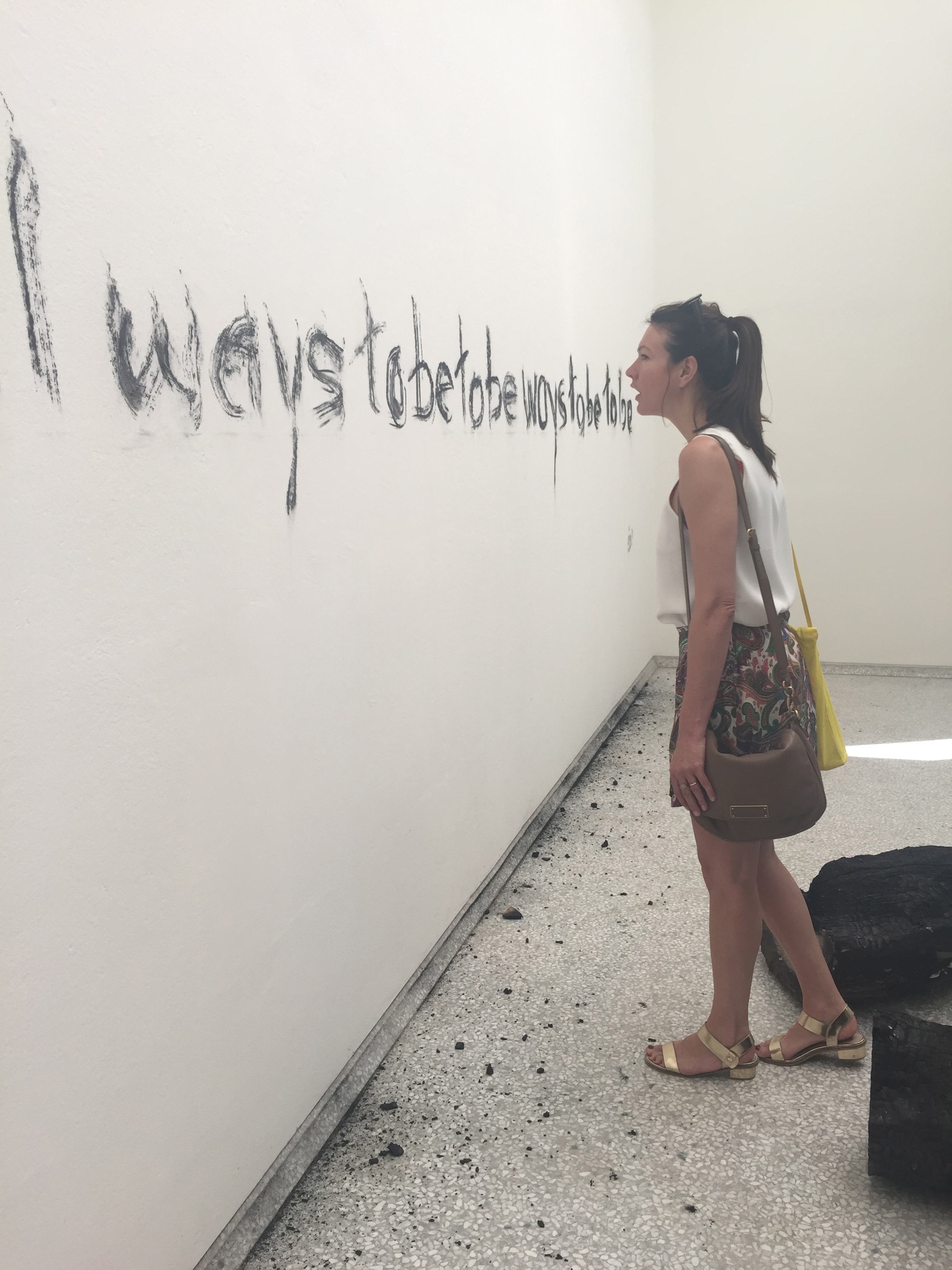

Also in the Giardini, the French Pavilion a beautiful Scottish Pine tree takes centre-stage in Céleste Boursier-Mougenot’s ‘Révolutions’ installation, bringing the outside in and inverting the traditional interior/ exterior relationship between gallery and environment. A recording of rising sap connects the Pine to trees on the exterior in a subtle sound installation. In the Holland Pavilion Herman de Vries has created another homage to the natural world in his ‘To Be All Ways to Be”, an installation of natural objects including a hippy charcoal slogan on the wall, which is a refreshing change from the ubiquitous neon signs that pop up all over the Biennale, and the rest of the art world. Artist-Composer Camille Norment’s sound installation “Rapture” inhabits the Nordic Pavilion, where shattered glass and water combine to create ambient noise that explores the relationship between the human body and sound.

At the Latin American Pavilion in the Arsenale is “Indigenous Voices”, a sound installation created by 20 artists, comprised of ancient South American languages emanating from speakers, which examines our bond with Mother earth. Away from the Giardini there are more exhibitions that take the natural world as a starting point, including Helen Sears, whose collateral event “…the rest is smoke” at the Welsh Pavilion (Santa Maria Ausiliatrice) features mesmerising video art mixed with photographs ,using natural phenomenon to explore temporality and mortality. A film featuring a mysterious red clad female in a wood, where red numbers appear on trees is distinctly Kubrickian, with a hint of ‘The Shining, and fittingly for Venice, a touch of Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 film noir ‘Don’t’ Look Now’, where the ghost of a red-coated girl haunts la Serenissima. In another room a simple film on a loop of birds chatter with a calming effect that offers a refuge from the intensity of the Arsenale exhibition.

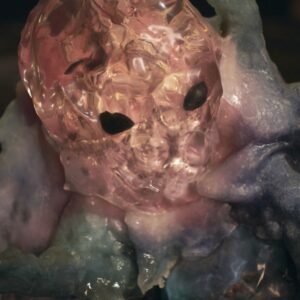

Despite the abundance of video and installation art in the Biennale, there is also a substantial amount of sculpture exhibited in satellite events around the city. Ursula von Rydingsvard’s breathtaking open air exhibition featuring 6 modular sculptures in the Giardini della Marinaressa, curated by the Yorkshire sculpture park and the “Glasstress 2015 Gotika” show, a collateral event at the Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti at Palazzo Franchetti, features some stunning new sculpture, drawing on the Venetian traditions of glass making, from an international selection of artists. Standout pieces include Kate Mccgwire’s ‘Siren’, The Chapman Brothers’ ‘The Same but in Glass I and II’, and Cameroonian artist Pascale Marthine Tayou.

Paintings are few and far between at the Biennale and periphery events, although there are some beautiful new Peter Doig oils at Palazzetto Tito, inspired by the Lion of St. Mark and harking back to 18th Century Venice when the populous kept Lions in their gardens, and a State Lion lived in a Golden cage in the Piazza. The Lion also references Doig’s home of Trinidad where it is associated with Rastafarian culture.

It’s also well worth taking a trip to the Cloister of Madonna Dell’Orto, next to the church where Tintoretto is buried. To experience the meditative beauty of Emily Young’s marble sculptures in Fine Art Society’s exhibition “Call & Response” is, without question one of the highlights.(“Chiamatae Risposta” is on until 22 November). The British sculptor’s conversations with stone have resulted in an exquisite collection of classical visages carved from marble, onyx and stone. At the entrance of the cloisters stands a monumental head of the Etruscan Sun Goddess. Touching the Tuscan marble I could still feel the heat of the day’s sun, and felt an instant connection with the earth. The earth and Mother nature is the inspiration behind the sculptures, and the artist explains: “Do we weep for what we have so thoughtlessly done to so many of our fellow creatures, our fellow life forms, now and in the future, who will fail to thrive, will suffer, will die?”

This quote could perhaps be a fitting epitaph for the underlying theme of the Venice Biennale, our relationship with the planet and the human beings and creatures that inhabit it, and what we are going to do to save it.