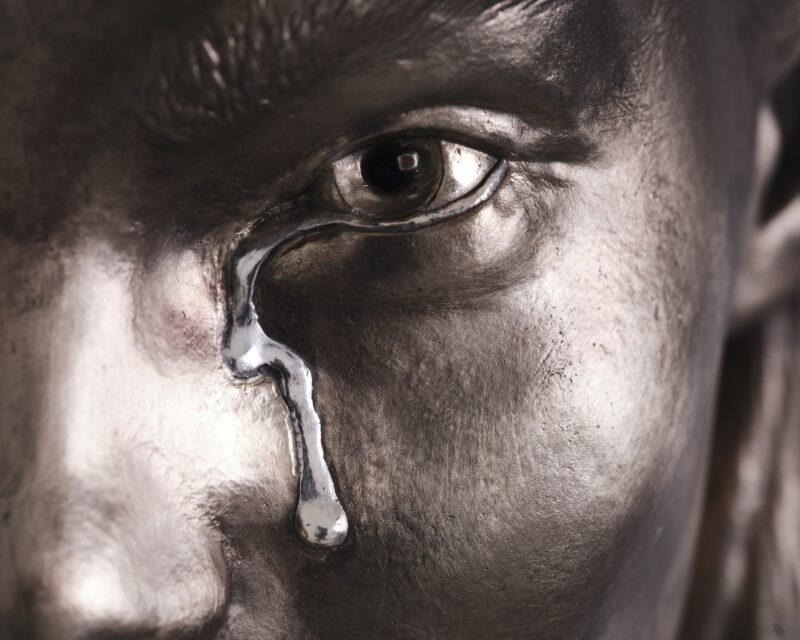

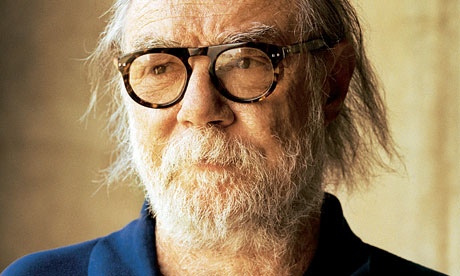

Paul McCarthy: He began his career in the 60s, but didn’t sell anything until the 90s. Until then, he was, ‘basically just a guy covering himself in ketchup.’ Photograph: Amanda Marsalis for the Guardian

I’m here in Los Angeles to interview the artist Paul McCarthy, I tell a taxi driver on a freeway past the skyscrapers of downtown. He gets really excited – the veteran video, performance, body and installation artist who is soon to have a show in Britain must be a local hero, I suppose.

“The Paul McCartney?”

“No, Paul McCarthy.”

The taxi conversation ends.

At the hotel, a film crew are setting up their lights. Location trucks drive in and out of the hacienda-style forecourt, bringing equipment, food and dog blankets. The stars are waiting in their cages. The movie is Beverly Hills Chihuahua 3. Out of the window of my room I watch a – human – wedding on a stage set up on a lawn that is bright green, under the gold desert blaze of the sky.

The location is Pasadena, a city sandwiched between the LA sprawl and the San Gabriel mountains. McCarthy has lived in Pasadena for most of his working life, and I am to visit his studio somewhere beyond the giant palm trees of the Hollywood Chihuahua-worthy hotel. The avenues of this wealthy suburb turn out to be dotted with film crews: Pasadena’s mansions, some colonial, some Renaissance, some Spanish-style, some aping log cabins, were built by Old Money as long as a century ago and offered hideaways to the first generation of film stars in the silent era. Today they make perfect movie doubles for Beverly Hills. I am proudly shown the garden where the Steve Martin picture Father Of The Bride was filmed.

Crossing the LA river back into the larger city, the film memories are unavoidable: that concrete channel with its trickle of water is a cinematic legend in itself. Lee Marvin, Point Blank. Charlton Heston, Earthquake. Arnie in Terminator 2, or is it 3…

I know I am here to study the art of Los Angeles County and to meet one of its most celebrated living artists – even if some locals do confuse him with a Beatle – but how can you concentrate on fine art in the city that for a hundred years has shaped the world’s dreams?

This is in the question I most want to ask Paul McCarthy. What does it mean to be a serious visual artist in the shadow of Hollywood? How can American artists cohabit, here on the west coast, with American popular culture so close to its phantasmagoric source? How, in short, can he compete with Beverly Hills Chihuahua 3?

Artists have in fact carved out a fascinating niche close to America’s film capital for the past 60 years. In the first half of the 20th century, Americans were more famous as art collectors than as artists. Picasso’s portrait of Gertrude Stein (1905–6) pays homage to the part rich Americans played in the art scene of early 20th century Paris – as patrons, for Stein and her brother were among the first buyers of avant-garde art. But then, after the second world war, with French culture shattered and depressed, a generation of American painters broke out for glory. They created epic, abstract visions of freedom, space, and of the very physical matter of paint and canvas, that brought the leadership of modern art across the Atlantic.

Jackson Pollock, the leader of this abstract expressionist movement, was by origin a westerner who had grown up mostly in Los Angeles, but like his peers, such as Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko, he lived and worked in the orbit of Manhattan. Another name for abstract expressionism is, indeed, the New York School. In the decades that followed, New York became the undisputed capital of modern art, its artists, gallerists and critics pushing neo-dada, then pop, then minimalism, then post-minimalism…

Meanwhile, in Los Angeles, everything looked different. “It’s interesting to me that so much of the minimalism of New York was grey and black,” says McCarthy, who has been watching as well as making art in Los Angeles County since the end of the 1960s. “And then you have the minimalism of LA and purple boxes and rainbow-coloured glass. You see the sky here in a different way.”

That’s the first thing anyone notices about Los Angeles: the immense, empty, shining sky. In 1966 one of the definitive California artists, Ed Ruscha, photographed that sky as a flat, silver blankness in a monochrome, deadpan work entitled Every Building On The Sunset Strip. He also painted it, ablaze. Ruscha’s images of the Sunset Strip record the second thing about LA that no one can miss – its boulevards, avenues and freeways. The artist Ed Kienholz used the car culture of the west coast as an image of American excess in visceral, sexually explicit installations such as Back Seat Dodge; when he died in 1994, he was buried inside a 1940 Packard coupe, driven into the yawning grave.

Kienholz was the most satirical and politically conscious of the great American artists, a splenetic and grotesque scenarist whose tableaux revile the American dream, mocking postwar affluence with dark echoes of the Depression and an atmosphere of fetid decay. This is another distinction of California art: much of it is angry, edgy and sceptical of mainstream values. That has a lot to do with the counterculture that flourished in 1960s California. But it is also a subversive response to working so close to the movie studios’ dream factory. In works of art such as Bruce Conner‘s decadent assemblages that mix pornographic imagery and fetishistic materials, the dark side of Hollywood feeds shady fantasies. Conner’s 1960 work Black Dahlia comes to mind as I contemplate the decaying pink fabric of the Mark Twain hotel (residential and transient) near the corner of Hollywood and Vine, in a neighbourhood of dead stars commemorated on the sidewalk and broken dreams littering the neon night.

“Auditions this way,” says the hand-scribbled sign taped to the wall. But this is not Hollywood and Vine. I am in Pasadena, and an electric gate has just slid open to let me into Paul McCarthy’s studio. Or to put it another way, to let me into Wonderland, Luna Park, Disney, all turned upside down, shaken in a jar, to make them rich and strange.

Artists have studios, and so do film companies. McCarthy’s is a wild cocktail of the two. As the audition signs tell you, this is a place where films get made, ambitious video productions that McCarthy screens in galleries as part of rollicking, scatological, baroque installations that sprawl as chaotically as the Los Angeles conurbation itself.

The studio is vast. It is a giant industrial shed with two main spaces that soar high as aircraft hangars. I am thunderstruck by the sheer scale of the operation. As for my question – how does a serious artist work so close to the culture industry of Hollywood? – part of the answer is staring me in the face. McCarthy has created his own alternative movie studio on a scale to compete with the official ones. You might call it BadDreamWorks.

It is, McCarthy agrees, “a kind of sculptural parody of an actual sound stage”. He’s a small, explosive, richly humorous man who momentarily makes me think of a Disney dwarf – but perhaps that is just because he is standing in front of a towering unfinished statue of Snow White. His dogs sniff around soppily as he explains huge rippling folds in the clay monument to the Disney heroine. These draperies were moulded from cardboard that had been protecting the statue but that one of his dogs tore to shreds: he decided to make the torn cardboard part of the design. By the time this sculpture is cast in bronze, it will have undergone further metamorphoses: a finished work he shows me is so pulverised and in his words “fucked up” that you can barely see its Disney smile.

But the most fascinating thing in McCarthy’s studio is the forest he is building. In the biggest space, a full-size fabricated tree already stands eerily in one corner. He takes me to the next room where a series of increasingly elaborate maquettes reveal what the finished forest will look like. An initial small model is rough, abstract and spontaneous, but a larger version already looks like a very spooky film set. Fir trees made of foam tower densely in a woodland straight out of a Germanic fairytale. In the middle of the forest stands a cottage. Who lives there?

Outside, the LA traffic whirrs by and the California sun shines. In here, a small gathering of people stand transfixed as McCarthy explains how his forest will grow from this model to fill the studio, and will then be the set for a film. I feel nervous for his cast. The forest is genuinely creepy, the witch’s cottage deeply worrying. It gets in your head.

In a video he made in the 1970s, McCarthy wears a woman’s silver wig and cavorts naked in his bathtub. As he moves about in the bath, he begins to apply various sticky organic substances to himself. He picks up a handful of raw sausage meat and tries to eat it. He gags, but keeps it in his mouth. Then his throat jolts and his face bulges with the effort not to vomit. Again, he keeps his mouth closed. Eventually, he is violently sick. He shoves another dollop of raw meat in his mouth, goes on plastering his genitals with kitchen sauces and bathroom products.

McCarthy was born in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1945. This was the city founded by the Mormons who trekked westward in the 19th century in search of their own brand of religious freedom, but he denies it was any different from other western cities as a place to grow up. His mother was a Mormon and his father was part Mormon but, he insists, his upbringing was not particularly religious. In fact his mother was a civil rights activist and his parents were delighted he went to art college. But it led him to a penniless and marginal existence.

McCarthy’s studio is, among other things, an index of his recent stupendous success. Only an artist whose works are selling very well indeed can afford to work on this scale, with a large staff who circulate merrily between computers and maquettes. This autumn he has shows at both the London and New York branches of his dealer, Hauser & Wirth, one of the world’s most powerful commercial galleries. But this is truly a rags to riches story; a Hollywood story, even, complete with the world’s most unexpected happy ending.

McCarthy began his art career in the late 1960s and has been here in Pasadena for most of it. But he did not sell anything until about 1990, he tells me. Until then, he was basically just a guy covering himself in ketchup in performances and videos that were made on a shoestring and seen by a handful of people. Perhaps the surprise, the thing to be explained, is not how he got ignored by the mainstream art world for so long but how he ended up rich and famous without once compromising or simplifying his disturbing, shocking, confrontational art.

In the 1990s, bodies, death and disease became the most potent themes of contemporary art. From Damien Hirst‘s work A Thousand Years, in which live flies feed on a cow’s head, to Lucian Freud‘s portraits of the performance artist Leigh Bowery, art rediscovered the flesh, the stuff of life. In the wake of this rediscovery, attention fell on McCarthy, who had been making body art since the 1970s and who was suddenly recognised as a contemporary master, whose influence can now be spotted everywhere from the Chapman brothers to Matthew Barney to British artist Nathaniel Mellors.

Yet it was partly because he was so broke earlier in his life that he started using household materials to make art, McCarthy says. Originally he wanted to be a painter. That still pervades his art: paint is a liquid, and so is sauce. As money got scarce in the 1970s, he found himself “switching from making paintings to using whatever I could fuckin’ find. Ketchup is cheap.”

Food also lent itself to grotesque bodily symbolism. “It just sort of led to the obvious. And that was that ketchup was blood. It was ketchup – but it could be blood. Mayonnaise was mayonnaise – but it could be sperm. Mustard could be shit. Chocolate could also be shit.”

In his performances, McCarthy wore masks, hats and false beards that turned him into characters such as a drunken sea captain who leads his audience on a voyage of vomit-inducing excess, and a painter who rants and raves while throwing about paint and other gooey substances on a giant brush.

As he has become wealthy he has – evidently, looking at his studio – put money back into his work to create ever more elaborate settings for his carnal romps. McCarthy’s videos now appear as part of diffuse, imposing installations that travesty such themes as the wild west and the pirates of the Caribbean. Whatever the narrative machinery, it all ends in ketchup and mayonnaise.

“I had this thing about exposing the interior of the body,” McCarthy says, “the orifices leading into the body, and what the interior was, and the taboos of the interior.”

Thinking about this, I start to see his fascination with set-building in a new light. All architecture is an image of the human body, an extra physical shell we make for ourselves. The sets McCarthy builds or finds are exterior shells, or empty skins, inside which his bizarre antics evoke the interior chaos of blood and guts. In his studio are artfully constructed rooms, full-scale interior sets that could have come straight from a TV sitcom. He did get his hands on a real TV set, from the show Family Affair, to use in a work he called Bossy Burger. Now, he tells me, he is about to take delivery of his most spectacular “found” film set.

“We start moving it next week: I just got an entire submarine. It’s a movie set. It was hard to get but I got it, and we have to move it, which is crazy. But I’m totally interested in moving this set from the north end of the valley to here: it has to come at night, in trucks. I’m really into this thing of moving this tube across LA at night. The submarine goes the whole length of my parking lot, it’s over 100ft long.”

The submarine set appeared in the 1996 film Down Periscope, a comedy vehicle for Kelsey Grammer. Now it will make its mysterious journey across LA, to become a surreal prop in the art of Paul McCarthy. As he describes it, the sub is a perfect bodily metaphor. Outside it is just a tube, like an intestine. Inside is a secret life.

McCarthy is in the great tradition of Los Angeles art. He revels in the freedom, the quirky tolerance, of California. He is a survivor of the counterculture who defies the taboos and mocks the beliefs of mainstream American society. He viciously caricatured George Bush. In his office stands a naked shop mannequin of… No… Can it be? Yes, it’s Barack Obama.

There is a glorious comedy about the fact that such a maverick, such a visceral visionary, has become rich and famous (at least in art circles). In a city where people desperately try to make it in mainstream culture, here’s a Hollywood success story that turns conventional values on their head. McCarthy made it by not making it. The drunken sailor got lucky. Now actors come to audition at a film studio where mind and body are turned inside out. Like Ed Kienholz, he makes art on a scale to defy and shatter the shoddy totems of reality.

How can art compete with Hollywood? By being bigger and bolder than the movies. As the sun goes down on Pasadena, the crew of Beverly Hills Chihuahua 3 are finished for the day. Paul McCarthy’s art seems more Hollywood than Hollywood. Among the palms, his Germanic forest haunts the empty sky.

Los Angeles has the most surprising and subversive art scene in America. Yet the city is a monument to everything that is not art. It is roads, it is malls, it is celebrity. Perhaps the joy of being Paul McCarthy is to be an artist in secret, to move submarines across the city at night. In London his exhibition will be huge. In LA he is undercover, subversive. This is a city vast enough to hold many realities, and the reality of the art world is just a fragment of the LA multiverse. On the way back to the airport, I enthuse about my interview with Paul McCarthy.

“You met Paul McCartney.…?”

• The King, The Island, The Train, The House, The Ship, runs from 16 November until 14 January 2012 at Hauser & Wirth London. His outdoor sculpture, Ship Adrift, Ship of Fools, will be on view until 16 February at St James’s Square, London SW1.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.