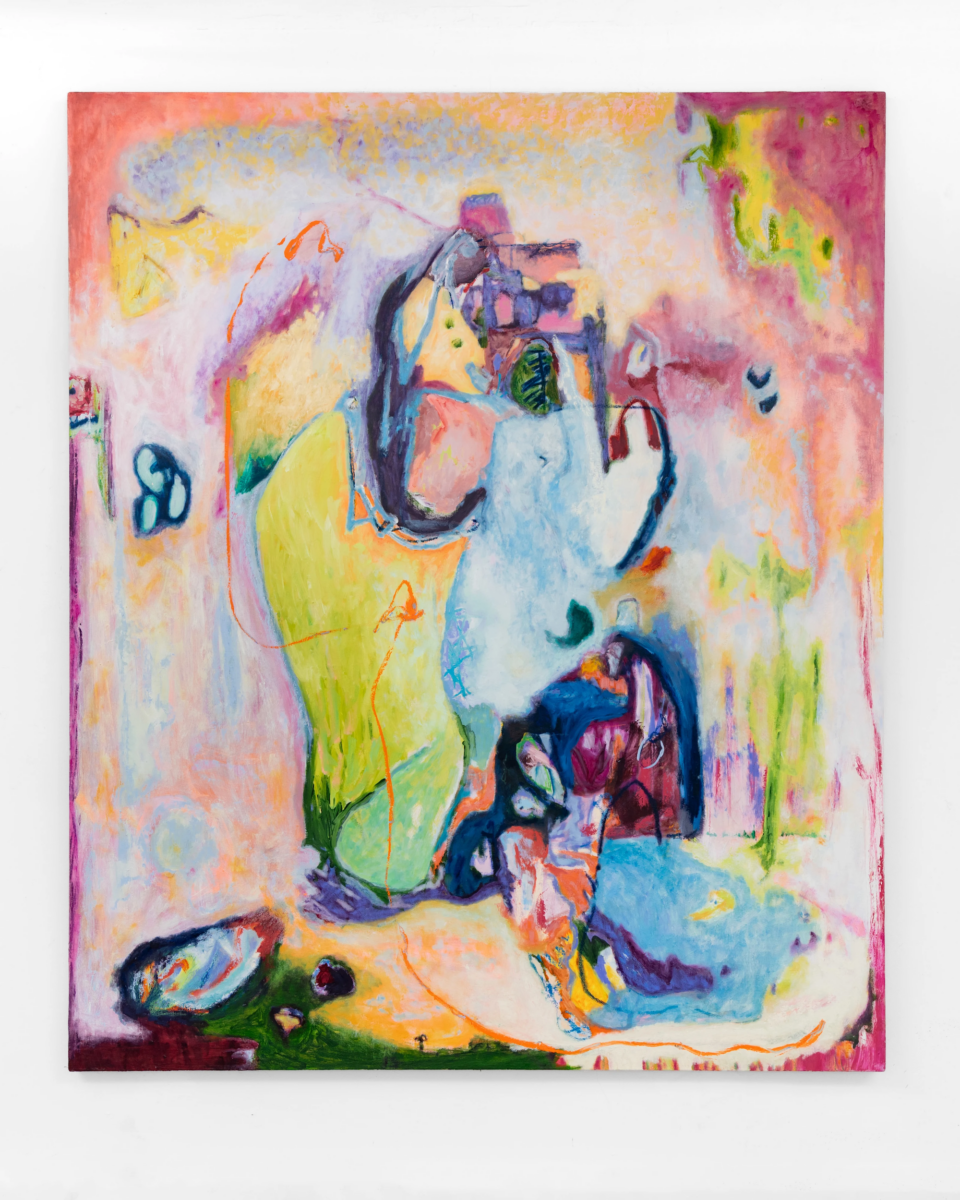

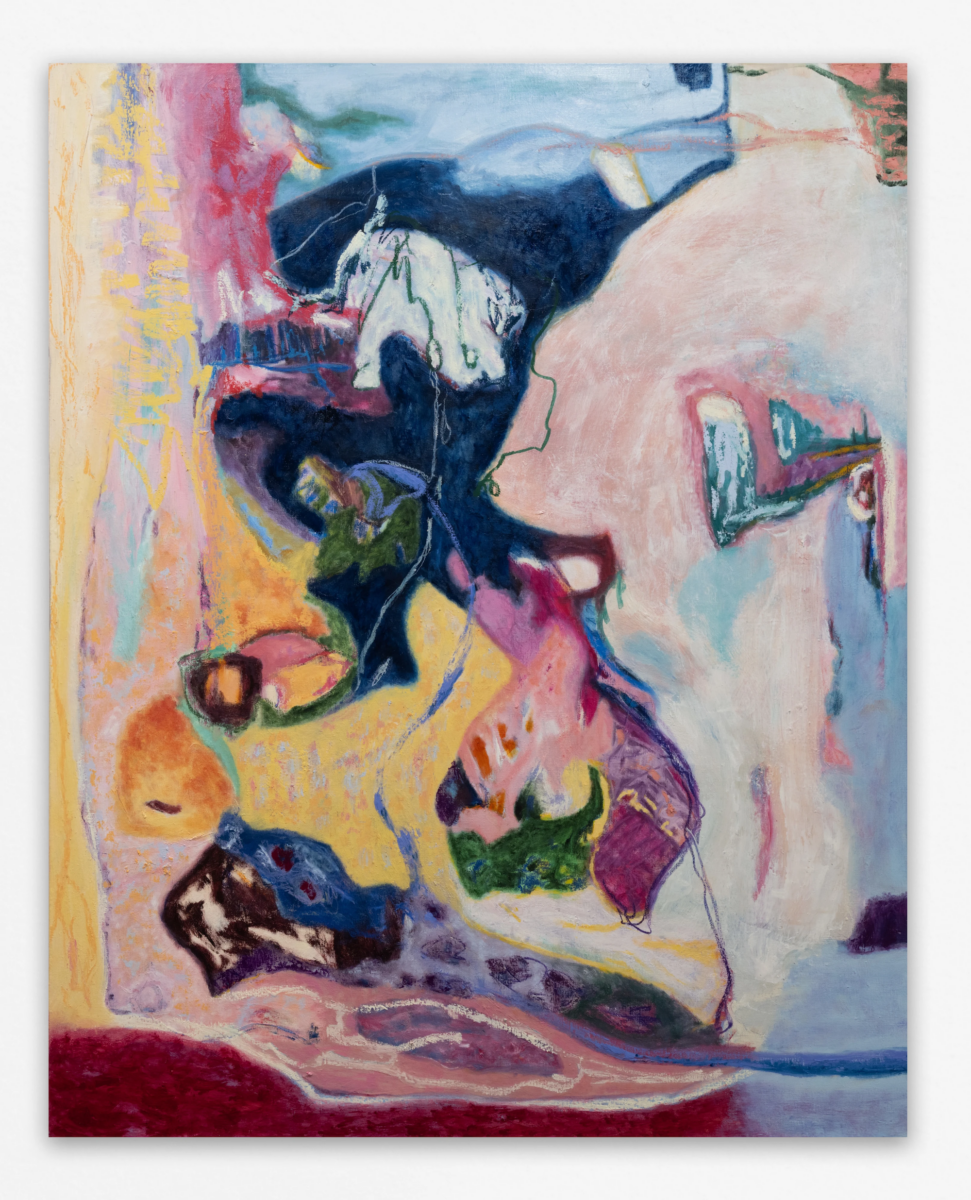

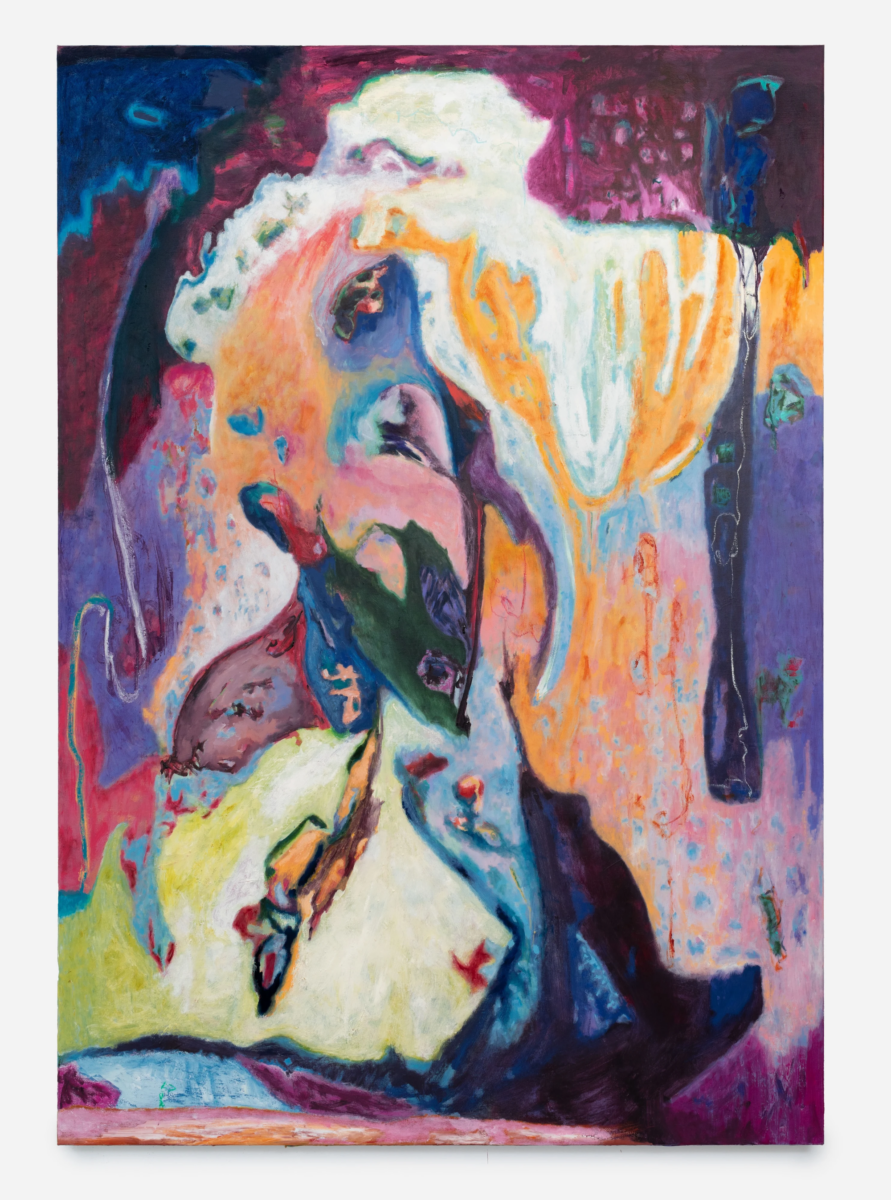

Sarah Dwyer is always playing, whether it is with scale, color, material or subject matter—but you’ll have to discover the cheeky references in her paintings for yourself, as she rarely explains. For “Slugger”, the artist’s first solo show in Paris, Dwyer brings her punchy palette, literary love and her family ties to the sport of boxing to the City of Light. It’s a knockout!

How does it feel to be returning to Paris? You’ve called it one of your emotional homes.

I lived in Paris in my twenties and worked for four years in an environmental economic research unit in Paris. And I went to art school for a bit in Paris, as well, after I left my job in economics. So, kind of all my mid twenties were spent in Paris and it is one of my emotional homes. A lot of my childhood holidays were spent in France—my parents are real francophones. I’ve always wanted to show in Paris, but an opportunity had never arisen. It’s very important to me, that’s why I’m so emotional. I’m doing it with a friend, Brigitte, which makes it even better!

How would you describe your visual language?

Well in 2020, I was invited to do a life drawing residency in the UK. It was life drawing in the landscape, like models in an old barn. I rocked up and I just fell in love within a few hours of being there. I would say my visual language has had a 180 turn since then, because I started doing life drawing and bringing the body parts and appendages that maybe have come into my paintings in the past and I would kind of negate, I’ve now embraced. That’s what I’m doing in the sculptures, I’m trying to give the suggestion of figuration.

The sculptures are really in dialogue with the paintings.

Yes, I do these works on paper, oil on paper. There are about five of those at any one time in the studio. At the same time, I’m playing around with the compositions of the sculptures on the plinths. They get fired two or three times. What I do is, after one part has been fired, I play with another piece and I think, “Oh yeah, I quite like the colors! What’s going on there?” I’m playing with that and I look at them and fire them again. Sometimes they don’t survive the multifire, sometimes it is just too much. So it’s quite risky, but I don’t mind. I quite like the risk of not following the rules of traditional ceramics. One day a week I make sculpture.

Is it always the same day?

Yes! On a Thursday.

You work across so many mediums, but the root of your entire practice is drawing. Is that correct?

It is. Especially in the last five years, I’ve really embraced drawing. During lockdown I did a phenomenal amount of drawing on paper and very large watercolors and gouache on big sheets of paper. I go to life drawing every Wednesday evening in a pub here in London and the drawings are almost warm up exercises that lead into oil paintings on paper that then lead into the paintings on canvas. I’m continuously playing with drawing and painting. The drawing loops back into the paintings later. You can see on the surface where I start with drawing, paint, paint, paint and then the drawing comes back into play with the use of oil bars at the end of a painting.

When I first saw your work, I immediately thought of the Fauves. Is there an influence there and what are your other sources of inspiration?

Massively! The foundations of my understanding of art history in my teenage years were very much European. When I was nineteen, I went to Chicago and I was thrown into American Modernism and Abstract Expression. Then in Paris, I spent a lot of time in galleries and museums. I kind of reintroduced myself to European artists in my twenties with this new awareness. Probably, it was an understanding of color theory and color and my research background that have brought the two together for me. So there’s that academic literary head, and then one foot in America and one foot in continental Europe. That’s the way I would describe how I’ve evolved.

You have a real interest in literature and poetry. Can you speak to how that has contributed to your practice?

For years I worked as T.S. Elliot’s wife’s assistant, so I went to an incredible amount of poetry readings and would meet poets on a weekly basis. I was kind of ensconced in this literary environment. Now, I listen to poetry in the studio a lot, Irish radio in general. At the beginning of my career in the mid 2000s, I used poetry and poets to title my all work. I would sit with poets and show the paintings over lunch and have them give me a title and they would (otherwise they wouldn’t get pudding).

The names of shows have even come from poems, right?

I did a show in New York ten years ago that was called “Sunk Under” based on Seamus Heaney’s “Bog Lands”. The show’s title refers to a line in the poem that says “butter sunk under” which is about the bog butter—butter that is preserved in the landscape for hundreds of years if not thousands. It refers to how the history of the land is preserved in the physical land itself. I think that the lyricism and understanding of poetry comes across in the paintings.

While we are on the subject of naming your shows, “Slugger” is quite a title and the theme is carried throughout the exhibition with titles directly referencing boxing like Sock It and Southpaw (a left-handed boxer). What is the significance of these boxing terms?

My father was a boxer and I used to box, myself, as a child and into my teenage years. A slugger is a style of boxer and I wanted to talk about the dance of a boxer and the dance of painting. The sluggers are ring generals, they might come across as brutish but they are actually the most skilled at ring-generalship. So I wanted to compare that and refer to the style of painting where there’s an element of aggressive use of oil bars and line. It kind of might look like I don’t know what I’m doing, but actually I do. *laughs*

Do you feel like when you’re painting it is a fight, as if you are in the ring with the canvas?

Oh, I go to war with paintings! Soaked in Petrol—I had a real battle with that painting. You just have to keep turning the painting and changing it and completely transform it and then go again and change it—fight with the painting basically. I can completely change the composition and the color palette of a painting overnight, then get up in the morning, look at it and think, “What have I done?”, but it’s good because at least we can start again now! That painting was a real battle, I changed it seven or eight times in the whole life of the painting. Soaking hands in petrol is what traveling Irish gypsies do. They put their hands in petrol to harden them before a fight.

I’m learning so much today! What are you working on now and something you are looking forward to?

Next year, I’m returning to Ireland, going back into the womb. The exhibition is starting in Cork at the Uilinn, West Cork Arts Centre and going to Highlanes Gallery, Drogheda, then to Limerick City Gallery of Art. Each show is going to have its own color theme, each color will be a Fauvist color and then I will respond to that color—it will manifest differently in each space. So from now, I’m working on that which is great. I left Ireland when I was fourteen, so it’s a great chance to say, “Here I am!”

Sarah Dwyer : Slugger – 30th November 2024 brigittemulholland.com