Alison Jacques has announced representation of the Estate of Bona de Mandiargues (b.1926, Rome; d.2000, Paris).

The artist has recently been the subject of renewed curatorial interest and international recognition. Her work is currently on view at the 60th Venice Biennale ‘Foreigners Everywhere’, curated by Adriano Pedrosa (until 24th November 2024) and ‘Surréalisme’ at Centre Pompidou, Paris (until 13th January 2025).

Alison Jacques will present a solo exhibition of Bona de Mandiargues’ work in 2025.

About the artist

Bona de Mandiargues (b.1926, Rome; d.2000, Paris) is considered a central artist within the Surrealist movement. In recent years, de Mardiargues has been the subject of renewed curatorial interest and international recognition, following her first institutional retrospective at the Nivola Museum in Sardinia (2022). Her work is currently on view at the 60th Venice Biennale ‘Foreigners Everywhere’, curated by Adriano Pedrosa (until 24 November 2024) and ‘Surréalisme’ at Centre Pompidou, Paris (until 13 January 2025).

De Mandiargues lived in Italy, before moving to Paris in 1947. Aged 6, her family moved from the Italian countryside to Modena. She described the move from rural surroundings to city life as traumatic, and she began to draw in response to this change in her environment. De Mandiargues went on to study at Accademia di Belle Arti, Venice, where her uncle, the poet and artist Filippo de Pisis (1896-1956) became her mentor. In Venice, she was introduced to influences she carried with her throughout her career; from the early Christian mosaics of Ravenna, the late medieval and early Renaissance painting from the Sienese and Ferrarese schools, to the Surrealists including Giorgio de Chirico.

Self-fashioning as ‘Bona’, she became an important figure on the Parisian post-war cultural scene, integrating within the founder of Surrealism André Breton’s intellectual circle. Bona experimented with oil paint, textiles and found materials, using painting and assemblage to explore ideas surrounding gender, dreams, and magic. As she wrote in her 1977 autobiography Bonaventure: ‘My research is alchemical… I want to make gold starting from excrement.’1

During this period, her work took on many of the tenets of Surrealism. In her paintings, fantastic creatures populate anthropomorphic landscapes. The creative environment in Paris proved extremely fertile: ‘Thanks to the Surrealist group’ she reflected, ‘I was able to see more clearly in myself what I had been trying to express.’2

Shortly before embarking on her trip to Mexico in 1958, Bona separated from her husband, writer and poet André Pieyre de Mandiargues (1909-1991), with whom she had a tumultuous relationship. Crowned by Breton ‘the most Surrealist country in the world’, Bona was inspired by the colours of Mexico, its pre-Columbian history, and local indigenous weaving, and entered a new artistic phase, abandoning paint in favour of fabric and collage.3

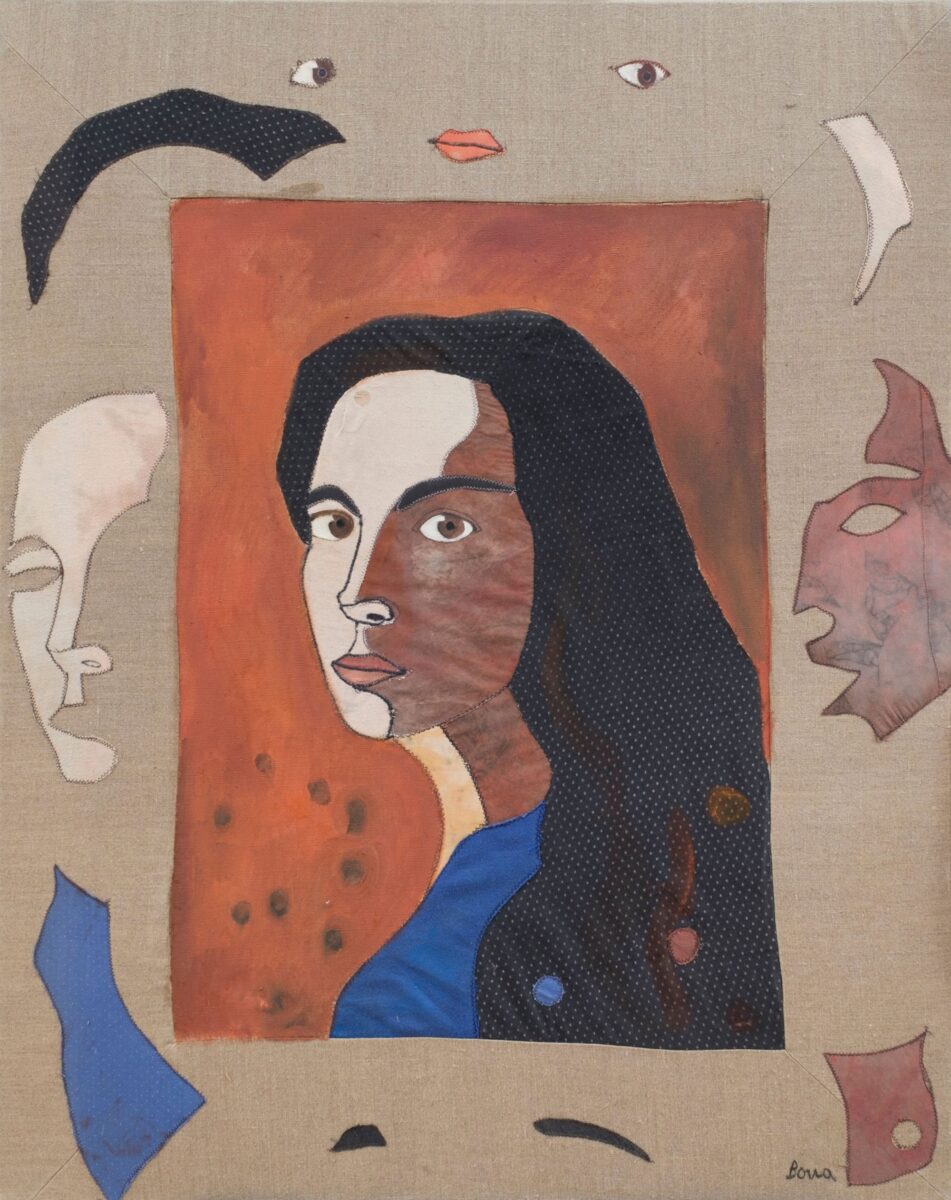

Taking scissors to her husband’s old jackets, Bona ripped out and disassembled the linings, which Italian and French tailors refer to as l’anima and l’âme (soul). The resulting collaged and sewn fabric images — which she referred to as ‘ragarts’ — read like paintings, pieced together with a sewing machine and also by hand. ‘I chose these very humble materials…I flipped inside out the vests of men to get to the heart of their armour, of their protection.’

In the work from this period, in the wake of World War II, she imagined the viewer, like her ‘ragarts’, as damaged souls, in need of restoration and care. The act of destroying an established whole — in this case a man’s jacket — and reconstituting it, mirrored Bona’s desire to rebuild the world according to her vision. As she stated, ‘an artist’s first duty is loyalty to the material; the second is the process of its transformation, so that it becomes something more by not abandoning its nature.’ By physically stitching material, Bona sought to rip apart established Western binaries, chief among them the concept of male and female; the beautiful and the savage; the spiritual and the material, fusing them into a single form.

Fundamental metaphors in Bona’s work are the snail and the eye. The spiral shell of the snail remained constant in her work, as she stated, ‘today I am a man and a woman in the same unit, I am like two forces which complete one another. The snail realises this union. Furthermore, I do not have a mind for collectivity. I am alone like a snail. I enter my shell as a whole. No one, from the outside, can see the bottom.’ Bona’s last self portrait (1994), shows eyes floating above her head, reflecting her thoughts that the artist is ‘a hand that has the eyes of its body and its soul’.