It is 1st November 2024 and all the leaves have fallen off the trees in Kelvingrove Park. Derek Jarman writes of Dungeness on this day in 1992 –

All Hallows. The dead circle the cottage in a high grey wind. I walk along the shore, the maroons go off and the lifeboat topples into the surf; all those lost at sea in the iron-grey waves. A calm has swept in. I’m not feeling so out of sorts this morning, only my sightless eye, absent in the morning, stares across the waves, but there is nothing there – no galleon with its mast down, no passenger liner turning turtle.

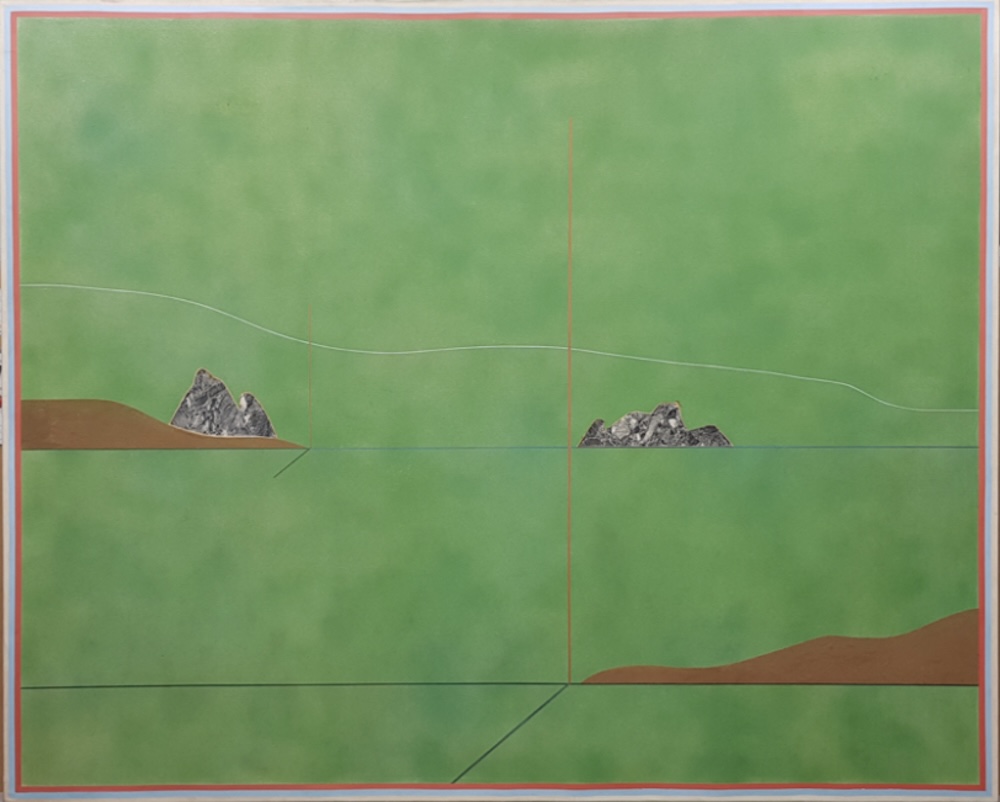

I am nowhere near the sea, I am in Kelvingrove Park in Glasgow, and I am walking towards the Hunterian Museum for the new exhibition on Derek Jarman. I arrive and the space is small, awkwardly cut into two; it seems a difficult environment, though managed with care and compassion. I choose to turn right and I face an early painting by Jarman – Landscape with Sandbars – that I recognise from the exhibition promotion and from a trip I took to Dungeness. Though made in 1967, several years before Jarman would buy Prospect Cottage, there are distinct echoes that anticipate Ness’ barren landscape, waiting for inhabitants as stakes divide and navigate the canvas. It is a blueprint, green for the garden and for this show.

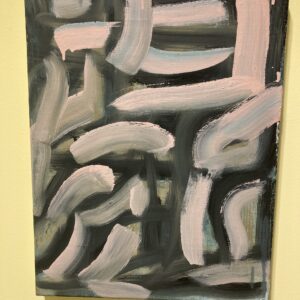

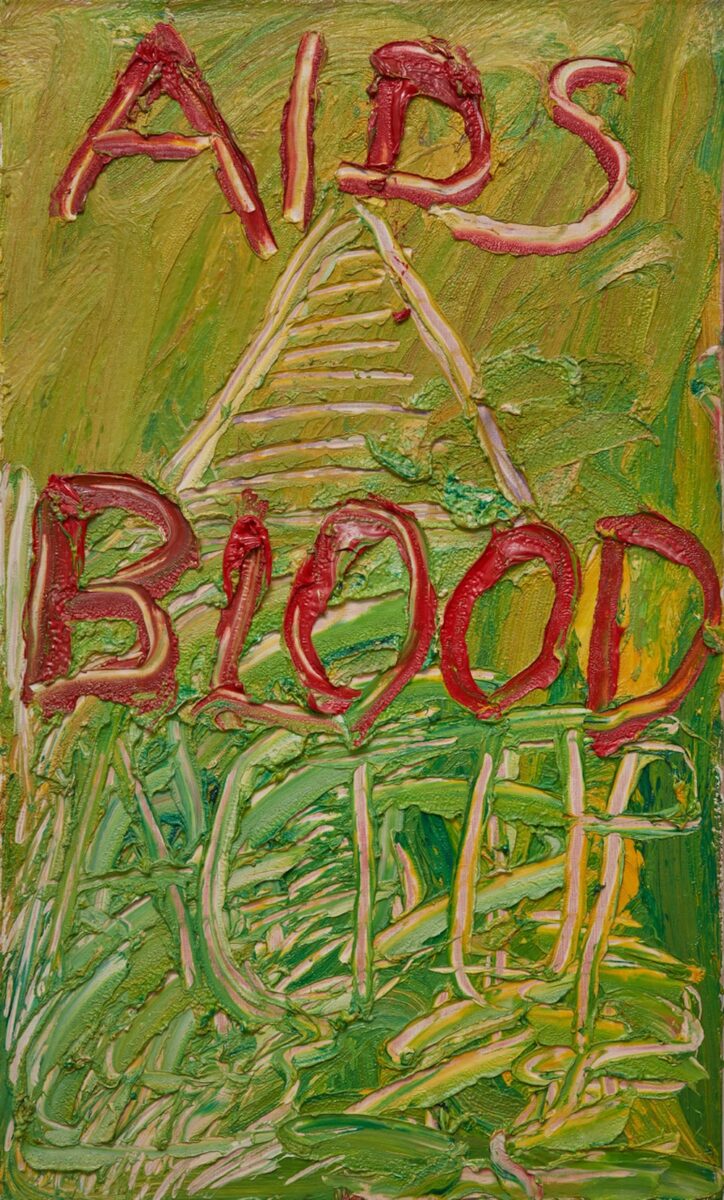

It is a rare oppourtunity to see such a range of Jarman’s work together, pulled from the archives of the Amanda Wilkinson Gallery, Keith Collins Will Trust and from friends of Jarman like James Mackay, his collaborator and producer. Large paintings are colourful and thick with texture – ‘positive’ carved upside down, half legible. Tarred black canvases line another wall, industrious and oily, threatening to engulf the ephemera lying on their surfaces. Then, a room darkened by curtain plays images of Fire Island, of a man, naked, holding a starfish, his body like a stake in the Dungeness garden. We move, as Jarman did, between forms and techniques, housed in the walls of the gallery.

In one corner, on a half wall jutting from the room, is pinned a piece of driftwood on which Jarman has attached a piece of glass, with an etched message found in Dungeness dated 1952, then above a pearl. The voice of the found letter haunts the piece, playfully assembled by Jarman with characteristic wit and care. Though the words do not belong to him, the piece embodies Jarman’s language of collaboration – with people and landscape; through the layers comes possibilities of being, together. The pearl placed above the letter, a visual pun on pleasure and desire, shimmers in the gallery light, a promise of the Dungeness horizon. There is a window around the corner but it is covered by a yellow sheet sticker: your vision is blocked, colouring the light. In it is cut letters, a list of flowers Jarman recorded one day as he looked toward the horizon of the Ness. As we read, against the window, we follow Jarman’s eye instead of our own and we look toward a new horizon.

Dug down in Jarman’s footprint, the exhibition grows: the show includes 5 contemporary artists who are held in dialogue with Jarman’s works and legacy. Andrew Black’s rural collages opposite Jarman’s tar assemblages; ‘Being Blue’, Luke Fowler’s film of Prospect Cottage runs back to back with Jarman’s film ‘My Very Beautiful Movie’; Tom Walker edits Jarman’s presentation at the Third Eye in his film ‘You’re saying exactly how I feel’, refusing Jarman’s celebrity image and to refocus on a community, gathered and listening; Matthew Arthur William’s photographs a fireplace altar with images and iterations of the artist, resisting singular meaning and identity; Sarah Wood’s film installations take up Jarman’s collage techniques to refollow his steps toward the Dungeness horizon. Wood will continue her project in an exchange of postcards to be displayed in the gallery one will arrive weekly. Jade de Montserrat’s performance piece is also upcoming, set to close the show in May responding to Jarman and the film Springtime in an English Village made in 1944 by the Colonial Film Unit.

Here, the soil of our histories and contexts is inhospitable. Jarman’s visceral scale paintings are a language of political resistance – ‘ACT UP’ he carves under ‘AIDS BLOOD’ written in red. Now, Williams’ photograph(s) excavate a land steeped in colonial legacy which de Montserrat’s work will approach too. In Wood’s film images of Keith Collins throwing rocks into the sea are shown with film of refugee children following the same motion. She wonders what Jarman would think of the world today; she doubts he would be surprised.

So we refind ourselves, inside and outside this garden gallery, between Jarman’s time and our own. We move now in urgent metamorphosis.

Jarman writes of this day again, a year later, November 1st 1993 –

In the evening we all went to Keith’s show, Brenda, Maggie, good old friends.

It is in community that this exhibition exists, and should exist – not just for Jarman’s ‘great glow of friends’ but for everyone who maintains his legacy and this show. The exhibition finds roots here also, mapping Jarman’s 1989 presentation at Third Eye in Glasgow. By refocusing the lens on the audience, however, Tom Walker orientates a new subject of the show: Jarman can exist, dug out of another time, but so do we – as flowers weeds, flotsam jetsam shored on the surface of this new garden. As Jarman’s work often does, the exhibition resists stillness and continues toward a perennial motion. Between artefact and activism, roots and leaves, the exhibition moves back, planting seeds, in order to move forward. It blooms, vitally, for the season when colour disappears and plants retreat.

Digging in Another Time: Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature is open now at the Hunterian Museum

Glasgow until 29th April 2025.