Catriona Robertson is a sculptor whose practice investigates the intersection of materiality, architecture, and environmental sustainability. Well known for her use of recycled and ephemeral materials, Robertson creates monumental yet transient sculptures that incorporate found objects and discarded materials, which feel almost performative and alive. Drawing inspiration from urban decay, ecological cycles, and the hidden geologies of cities, Robertson invites us to reevaluate our relationship with the built environment and the waste we leave behind.

Robertson’s work is intrinsically linked to the concept of the urban landscape itself as a living collage in which architecture forms a kind of urban geology. She draws inspiration from the layering of history found within cityscapes, where organic and inorganic elements intertwine.

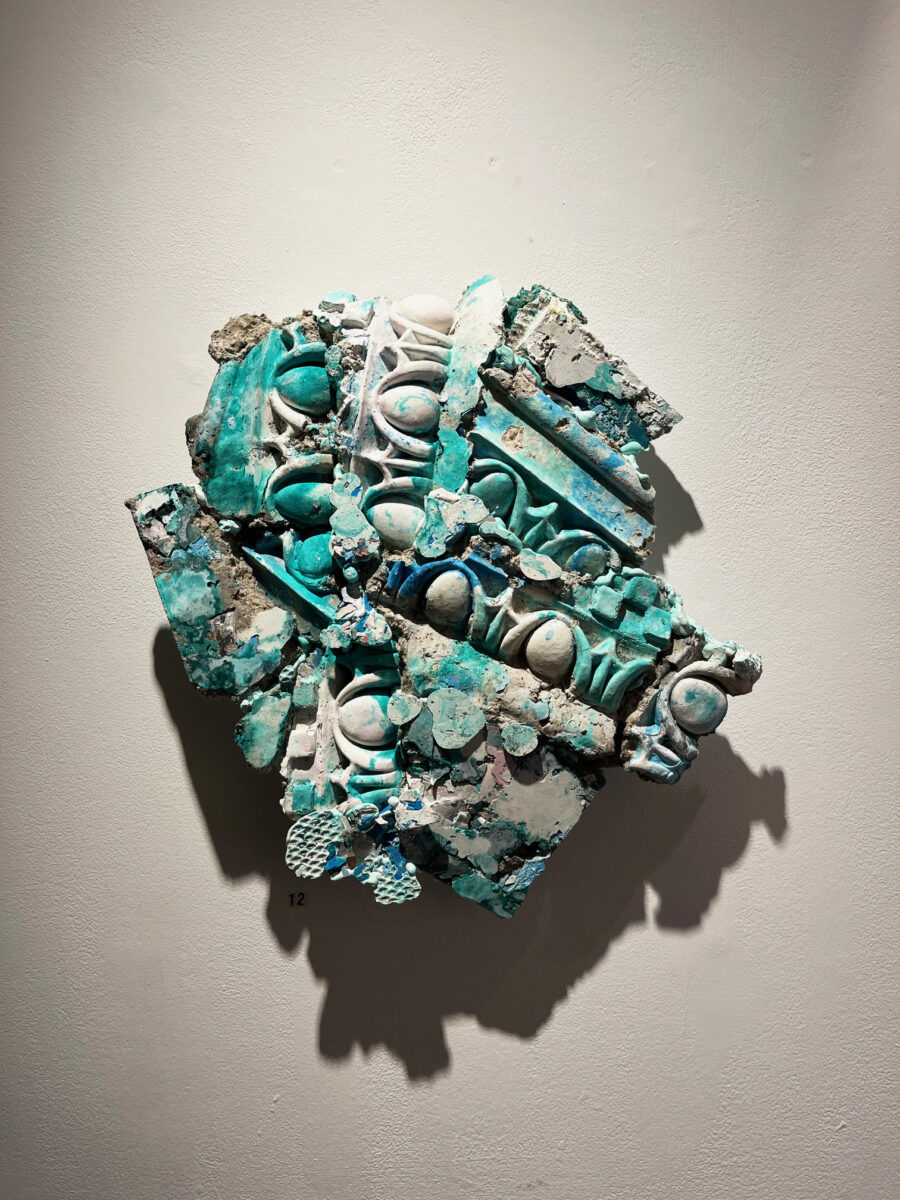

Through Robertson’s use of reclaimed and recycled materials, she critiques societies’ throw-away culture, suggesting that human detritus will become the bedrock of our cities, pressed into sediment and stone. She installs monumental, worm-like beasts, somehow burrowing and crawling through an exhibition space, consuming and reusing materials as part of their evolutionary cycle. The worms are both robust and vulnerable, as they are broken down, amended and reformed; they present the fossilised iterations that have come before. Robertson’s process of repurposing and appropriating component parts of previous works mirrors the fleeting nature of urban life as we build and the inevitable decay that follows, capturing the ephemeral and ever-changing nature of urban environments.

Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your background?

My sculptures imagine a narrative of a post-human future in which nature comes back through the cracks of concrete foundations. Gargantuan worm-like creatures have adapted to digest these synthetic materials compressed over time, excavating new-age sediments and re-constructing future architectures. ‘Gigantic Pile’ has been on a journey with each new iteration of deconstruction and reconstruction it takes on a new form, absorbing a hybrid outer shell. It began as a symbol of future ruins, which have since transformed into something more organic, a metaphor of a worm digesting and recycling residue materials as sediments of the future. Within its carved-out pathways it longs to reconnect with nature, evolving out of the age of the Anthropocene and the impending climate crisis.

Since graduating from my MA at the Royal College of Art I was selected for the Mark Tanner Sculpture Award Graduate Residency in 2020. In 2021 I was runner up UK New Artist of the Year, Robert Walters Group, with an inaugural exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery and since then I’ve had a lot of interest in my work. I was shortlisted for the Ingram Prize 2021, won a studio prize at SET studios and I was awarded the Muse Gallery Residency in London. In 2022 I was selected for the Gilbert Bayes Award by the Royal Society of Sculptors. I was commissioned by the Merz Barn in the Lake District to create my work ‘Gigantic Pile’ as part of a residency and 75th Anniversary. The Saatchi Gallery curators saw my work in the Lake District and commissioned me to showcase ‘Gigantic Pile’ at the Chelsea Flower Show 2023 in London, sponsored by HSBC which was a fantastic opportunity, and following this I was nominated for Women of the Year 2023. During 2023 I was Artist in Residence at Benson Sedgwick which significantly helped me to create the Chelsea Flower Show commission, selected by the Royal Society of Sculptors as part of the Gilbert Bayes Award. I was then invited by the Art House in Wakefield to create a site-responsive public sculpture at the front of the building which has been on show to the public since July 2023 and has been extended into 2025.

Earlier this year I was invited to show my work again at the Saatchi Gallery by the Director, as part of the exhibition Everyday Monuments. My solo show ‘ I am the Landscape’ has just opened at the Muse Gallery and is open until 20th October.

Your large-scale sculptures must be difficult to manage which are traditionally expensive to create and sell. – How does breaking and rebuilding your sculptures in new configurations change or even reinterpret the meaning of the work to you?

I’ve been lucky to have done several residencies in large post-industrial spaces which have been both inspiring and have enabled me to keep working on a large scale. It’s a lot of work to install my work physically and it’s re-made each time differently. I’ve had additional support from a residency at Benson Sedgwick, as part of the Gilbert Bayes Award, the Royal Society of Sculptors, the Saatchi Gallery, the Art House in Wakefield, as well as invitations to show my large sculptures at the Bomb Factory and a recent residency at the Zig Zag Building in Glastonbury. I work on a surprisingly small budget and have build ideas of recycling into my practice. My biggest cost is my studio and transport of my work which depending on the scale of the show I sometimes get help with from the gallery. I’ve been quite lucky to have had support for my studio where I won the SET studio prize, the Muse Gallery residency and the second prize UK New Artist of the Year award, which has meant I’ve been able to keep making work since graduating. It is not easy to make a living as a sculptor, especially in London, and I’m still looking for a balance as I develop my work. I also teach Metalwork / Sculpture as a Technician at UAL so I’m balancing my job and my practice. I’m always using recycled materials – newspaper -( discarded Evening Standard / Metro), cardboard packaging, recycled timber, reclaimed metal and recycled textiles which keeps my costs low and I am able to reuse a lot of these materials. For larger commissions, such as the Saatchi Garden RHS Chelsea Flower show, for example, I re-used a lot of materials which I’d collected during another residency at the Lake District.

In most cases, I am able to flat-pack my large worms and they often only exist at the exhibition space, responding to a site as a new variation. There’s an integral structure which is modular, made of timber/plywood (which fits into my small car!) and I cover it with cladding. Sometimes I collect additional cladding material on site – such as during my latest residency ‘As Old As the Hills’ in Glastonbury, I was next to a building site and there were some scrap materials I was able to work with to create the ‘Golden WYRM’. Sometimes using discarded textiles, carpet, underlay and lino, things which are often being thrown away.

I find this constant construction and deconstruction of my work interesting, like the constant changing of time and reforming of landscapes, cityscapes, and buildings being brought down and rebuilt. This idea of a building being a throw away consumerist material, discarded, unlike something being protected, such a ruin… buildings need to be either 100s of years old or a ruin before they are looked after and preserved.

You have an exhibition coming up at Muse Gallery ‘ I am the Landscape’. Can you tell us a little about this exhibition?

Visitors can enter a subterranean urban strata of dreamscapes and look through wormhole portals to otherworldly post-human dimensions.

Having lived in London for many years, I’ve been thinking about how disconnected we are from everything natural. We are living in a human-made landscape in which few truly wild places remain. City parks, national trust gardens, pebbled beaches, gardens, potted plants… this type of nature is designed, manufactured, maintained. Trees are evenly spaced with hedge rows neatly trimmed, only certain trees are cultivated and to an extent, what we perceive as nature isn’t very natural and this is only a glimpse. I’ve been learning about rewilding and the importance of biodiversity, fragile ecosystems both on land and in the ocean, with nature taking back control and finding a way to live on its own terms. I became particularly drawn to how plants begin to grow between the cracks in underused areas, often dominating and becoming spaces that are incredibly bio-diverse. I am a Landscape draws together these ideas of how nature has survived for millennia, and how humans have been able to affect the landscape so dramatically in such a short period of time… over the past 200 years since the Industrial Revolution, there has been a systemic shift and its shocking how governments are sidelining this issue. How can we become good ancestors? What positive changes can be made and how can scientists, governments, arts and the public become more intertwined and symbiotic in how they live. My sculptures are an embodiment of future ruins, a new landscape intertwined with nature, so that’s where the ideas of sediment, water, lichen and layering come in. It’s about remembering that we are a part of nature and not separate – I am the Landscape.

Nicholas Stavri: Your sculptures often refer to monumental materials such as marble, but you always use lighter substitutions for them. What does that tension between permanence and transience mean to you?

By referencing those deep time natural building materials – marble, stone, I am thinking about what these words and materials mean. For example the verb concrete, conveys something permanent, strong and everlasting. But in reality, modern concrete is brittle especially when compared to Ancient Roman concrete. I’ve been fascinated by the idea of concrete being ugly, ubiquitous…like a throwaway material. By making the surface of my sculpture appear more like marble I am questioning concrete’s place in Deep Time and the way that future Geologists can share a story by looking back into our history of this synthetic stone and see the impact it is having on our environment. I’ve developed my own recipe for paper-concrete, using recycled newspaper pulp and cardboard packaging, thinking about irs sustainability and the papercrete to make the sculptures resemble marble, the use of this material stems from my research into agroecology in Architecture, It was during the Mark Tanner Sculpture Award Graduate Residency at the Standpoint Gallery where I developed a method of producing paper-clay that allowed me to mould and form the pulp into a way that allowed me to imitate marble and stone. The paperclay really did open up a conceptual avenue of exploration, allowing me to work in a more flexible way with a material that has unique and strengths. I suppose transience and permanent relates to the things we ultimately lave behind. Like a footprint In the sand, turned into a fossil millions of years later. A moment in time can become something precious, hardened but also disappear as memory. I think I am questioning concretes suitability as a monumental material – to hold memory, as with industrial waste and synthetic plastics. Will these synthetic materials create new fossils – memories in the same way? Are they just passing moments which disappear ? Does it even matter?

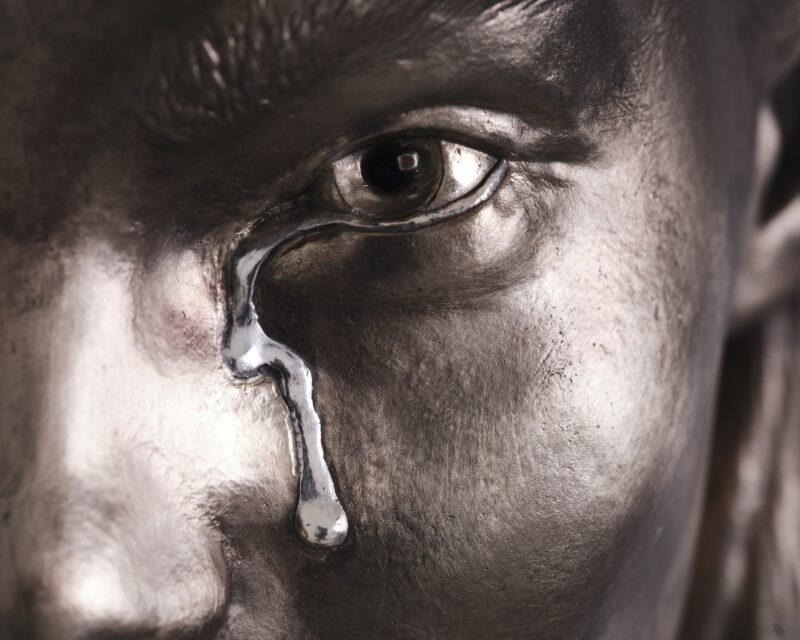

We place value on things which last, like gold and marble, precious stones . But what of the intrinsic value of things that don’t last in time which we cannot see, memories, relationships, microscopic cycles in nature, elements on the edge of peripheral vision. I’m often questioning this tension of time and how it is measured. I’ve been told my sculptures look like artefacts, future ruins, and future fossils. This displacement of time on the surface of my sculptures – the unknown of past present and future- is the feeling I’m trying to create. A geologist has even said to me they thought my work looked lost in time! So maybe it’s working.

Nicholas Stavri: Your installations often create a tension between fragility and strength; often, large forms can be perceived as both monumental and precarious. How do you think this tension reflects larger social or environmental concerns?

I see the column being a symbol of power and hierarchy and how that is fragmented and twisted and collaged into an object that moves through space, often into a floor, or through a wall.

The traditional supporting structure seems to have transformed, from ruin into something more organic, moving through space and time engulfing and growing with every incarnation. Worms are the architects of the soil, they make castings and tunnels and they really do reform the soil…renewing the waste that we leave behind, without concern for what our now mostly artificial sedimentary layer says about us. I’d like to tell a story of reflection, repurposing and renewal, encouraging others to consider human impact on nature, and how to work collaboratively with nature.

How are the smaller works going since I saw them in the Saatchi shop?

I have been making smaller works which explore more intricate elements of my research – ammonites, fossils and architectural remnants. Using 3D scanning and mold-making as a part of my process.

I sold a wall piece at the Saatchi gallery so that was really good. It’s much harder to sell the big pieces! (near impossible) .I have developed smaller works recently as part of my exhibition ‘I am the Landscape’ with a really good response. I’ve been exploring my ideas in more depth as a result. I’ve included ammonites, conch shells and ram horns. Using a combination of 3D scanning and mood making, I found an ammonite fossil on a beach in Dorset, and have scaled it up as a 3D print, which has then been cast in various scales in my paper concrete and some new ceramic sculptures. I feel these smaller pieces form a wider part of my narrative, surrounding these ideas of future fossils, remnants, fragments of architecture and urban geology. I’ve scattered these throughout the exhibition almost as if an excavation is taking place or a deep sea dive, the viewer becomes the future archaeologist.

I’ve also been scanning architectural features around London, 3D printing them as moods then casting them in what I call my ‘signature’ recipe paper- concrete in a collage-like painterly process. I join the fragments together and they feel like part of some kind of future museum display. These small works wouldn’t have come without the big sculptures, so it’s all connected and I’m excited to continue making them. If you do know anyone looking for a 5m gargantuan worm sculpture though, let me know!

Do you have a gallery?

No I don’t have a gallery. I have had some success selling my smaller wall works at exhibitions though this is slow progress. I recently became a part of `Gertrude’ founded by Will Jarvis, previous founder of the`Sunday Painter’. It’s an art app where potential collectors can follow artists, and hopefully bridge that gap between gallery artist and collector. It’s launching in October. They don’t represent you as such so you are free to work and collaborate with galleries. I’m not sure if I want a gallery at the moment as I would need to be a collaborative process, though if the right one came along then I’d consider it.

What books are you reading at the moment?

Robert Macfarlane – Wild Places – I love all his books, Gathering Moss – Robin Wall Kimmerer , Wild wood – Rodger Deakin, Becoming Animal – David Abram

Finally, what do you have coming up?

After my exhibition at The Muse Gallery, I’ve been Shortlisted for the Cass Art Prize 2024 and there is an exhibition on November 8th -16th at the Copeland Gallery, London also in November ill be at the Woolwich Contemporary Print Fair 21-24th November finally next year ill be exhibiting some sculpture at the Winter Sculpture Park in Thamesmead.

Catriona Robertson, I am the Landscape, 26th September – 20th October 2024 The Muse Gallery

Thursday-Sunday 12-6PM or by appointment Closing event 19th October 3-6PM

Intro by Nicolas Stavri