I went to the Venice Biennale for the first time in my life, often dubbed as the ‘art world olympics’. As a freelancer working across the European arts I assumed Biennale to be what drew me to such art in the first place – the raw passion, sheer excitement and brilliance, the accessibility and understanding it provides to individuals. I was wrong.

The Biennale proved to me that the Western European art world is done – not necessarily in a negative way. It’s highly successful, world-renowned, based on historic institutional models which provide great cultural history and tourism. With that however, lacks a sense of fear, bogged down with pressures to meet expectations as opposed to creating new expectations. I am in no way saying that the artists and curators involved in pavilions were lacking, in fact the complete opposite (John Akomfrahs GB pavilion was a standout for me, as was France), but the levels of expectancy to reach certain oeuvres means less surprise, and more expectation from the viewer – a pressure to maintain, not surprise on behalf of the participants.

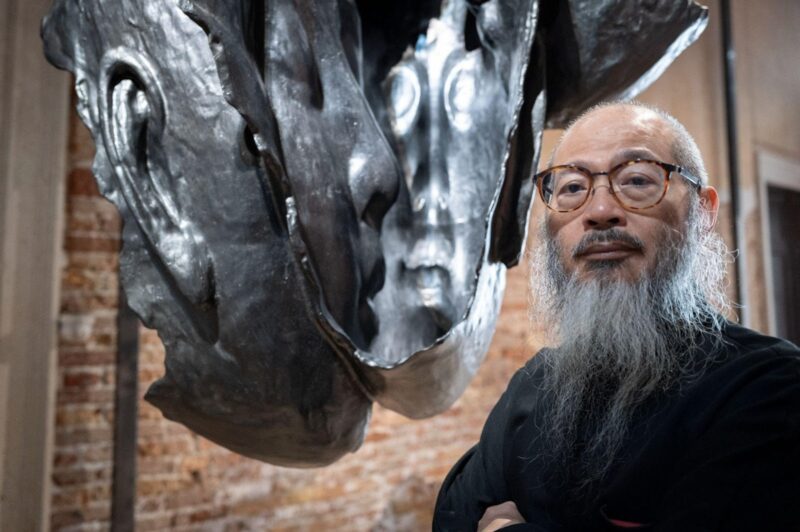

Having access to this event allowed me to witness the difference in communicating art, traditions and cultural values across the world, the créme de la créme representing their respective fields and country – and for me, Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa are the underdogs. The passion I was longing for was felt in the countries removed from the west – Mongolia, Benin, Saudi Arabia, Poland, Nigeria. In these areas I witnessed what made me fall in love with art the most: raw, unfiltered, unapologetic expression. Radical feminist scripture and discourse is heavily communicated in Saudi’s pavilion, Mongolia features crazily conceptual skull-deities linking to historic ancient traditions, Poland platforms Ukrainian settlers via dystopian Karaoke performances – Nigeria calls for the British Museum to return stolen artefacts. All risky, captivating moves to exchange cultural values and importance in an extraordinary, somewhat anti-establishment way.

Compared to the West, where it felt you had to know in order to know – pavilions representing Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa made significant efforts to engage audiences through various efforts. Tours and talks were much more common, events were heightened as far and wide as possible, thoughtful gifts were given (like traditional handmade paper from Korea!). Perhaps there is less pressure to succeed as a country outside of the west, but instead a chance to show off something radical, take a risk, and hope that one day the gaze shifts further east.

To conclude this piece, I want to reiterate that my views are in no way connected to the artists and curators, but the frameworks in which Western art has found itself. The audiences which the Biennale attracts during the press preview are indeed there to enjoy – but also work, show face, schmooze and fit in within the landscape. Being surrounded by the public audience after the press preview helped bring the art back down to earth, acknowledging that I do indeed love the creative world and the feelings it evokes, but the western side of the industry – not so much

The Biennale Arte – November 24, 2024, Venice labiennale.org/it/arte/2024