Meike Brunkhorst – writer, publicist and art marketing consultant – introduces a new series on museums rewriting cultural history – first up some highlights of exhibitions embracing postcolonial perspectives.

Halfway through January, 2023 reviews and 2024 previews are shaking hands. A last chance to catch up on some major exhibitions that deserve more attention than a quick browse before the new year gathers momentum. 2023 ended on some strong shows that indicate a fundamental shift in what is presented at public cultural institutions.

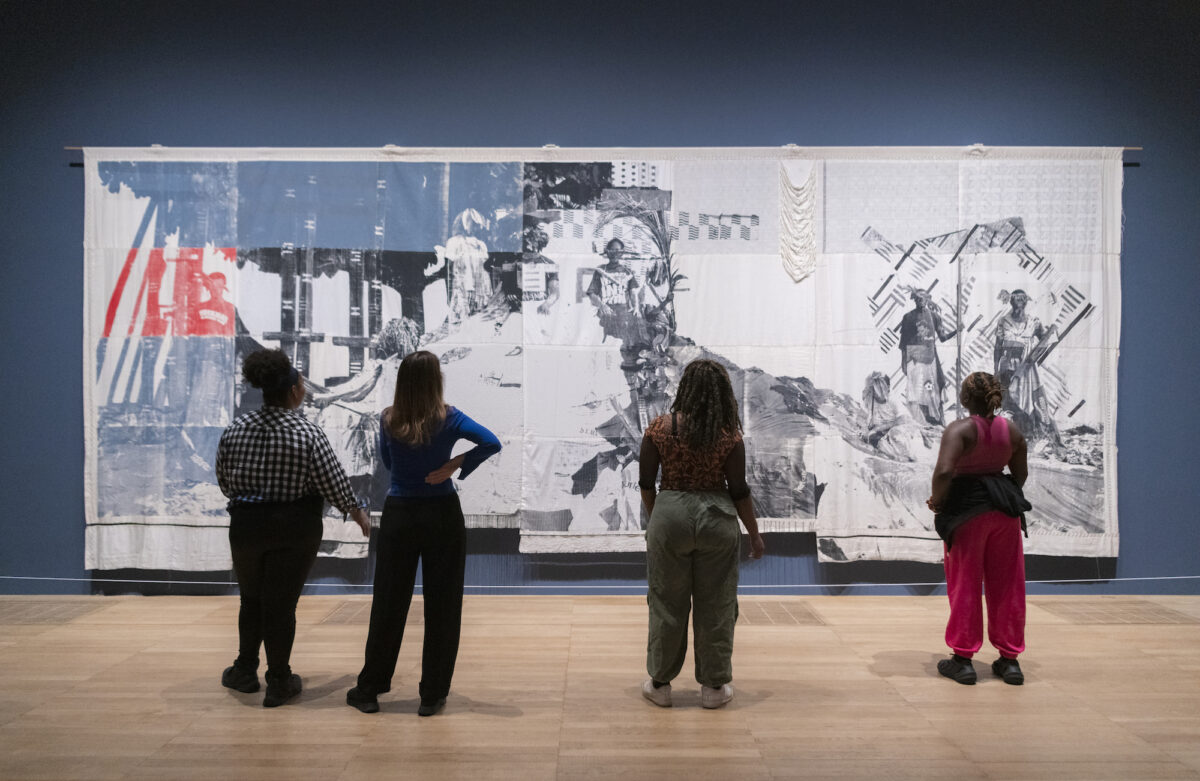

Having visited related panel discussions and offsite spinoffs, I finally visited A World in Common at Tate Modern in the last week of its 6-month run. Rather than presenting African art as precious collections of exotic objects, here contemporary artists from across the continent capture wide-ranging narratives in photography – a genre traditionally associated with predominantly male gaze and imperial view of the world – wall texts providing meaningful introductions to approaching culture as shared human experience.

The counter histories introduced in the exhibition stand in stark contrast to the permanent displays of celebrated masterpieces in most of London’s national collections. Many have been re-hung and re-contextualised since Alice Procter ran her ‘uncomfortable art tours’ between 2017 and 2020, adding context missing from the wall labels. Paintings read differently when you understand the circumstances that led to plantation owners’ wives depicted in exotic settings, or black children in Victorian costume. Details of the routes many antiquities took to become treasured parts of British history should be acknowledged, whether you believe these should be returned to their countries of origin or not. I hadn’t finished reading her book The Whole Picture on ‘the colonial story of the art in our museums’ when the Colston statue was toppled in the wake of the George Floyd protests.

Just as postcolonialism is not to be confused with an end of imperialism, it is not restricted to themes of racism, nationalism and migration, but covers issues ranging from intersectional feminisms to cultural, national and gender identity as well as ecological sustainability.

Winds of change had been gathering for a while by then and could be felt as far back as the Venice Biennale back in 2019, in itself a somewhat outdated institution.

One of the most talked about displays that year was the Lithuanian presentation of an opera performance staged on an artificial beach. Created and curated by women, Sun & Sea addressed the social and environmental impact of everyday activities. Nowadays considered an elitist and gratuitous pastime, the history of opera includes a healthy dose of dissent, defiance and resistance, not least to Italian fascism. The Chilean pavilion featured a decolonial opera performed by a trans singer as a chapter of Voluspa Jarpa’s Altered Views which also included a Hegemonic Museum where European museology with its human zoos, mockery of women’s rights and mental patients becomes the spectacle, contrasted with examples of Western cannibalism and the origin of banana republics. Probably the first time I seriously questioned the history and purpose of museums once I looked up the definition of ‘hegemonic’.

The 2019 edition incidentally was the first to achieve gender parity in the biennale’s history, 124 years in. Which brings me back to the present and the fantastic exhibitions dedicated to women artists last year, including the Royal Academy hosting Marina Abramovic as its first major solo show by a woman. I also finally read the catalogues for Re/Sisters and Women in Revolt, which are essential additions to any feminist library – and a great starting point for rethinking institutional curation.

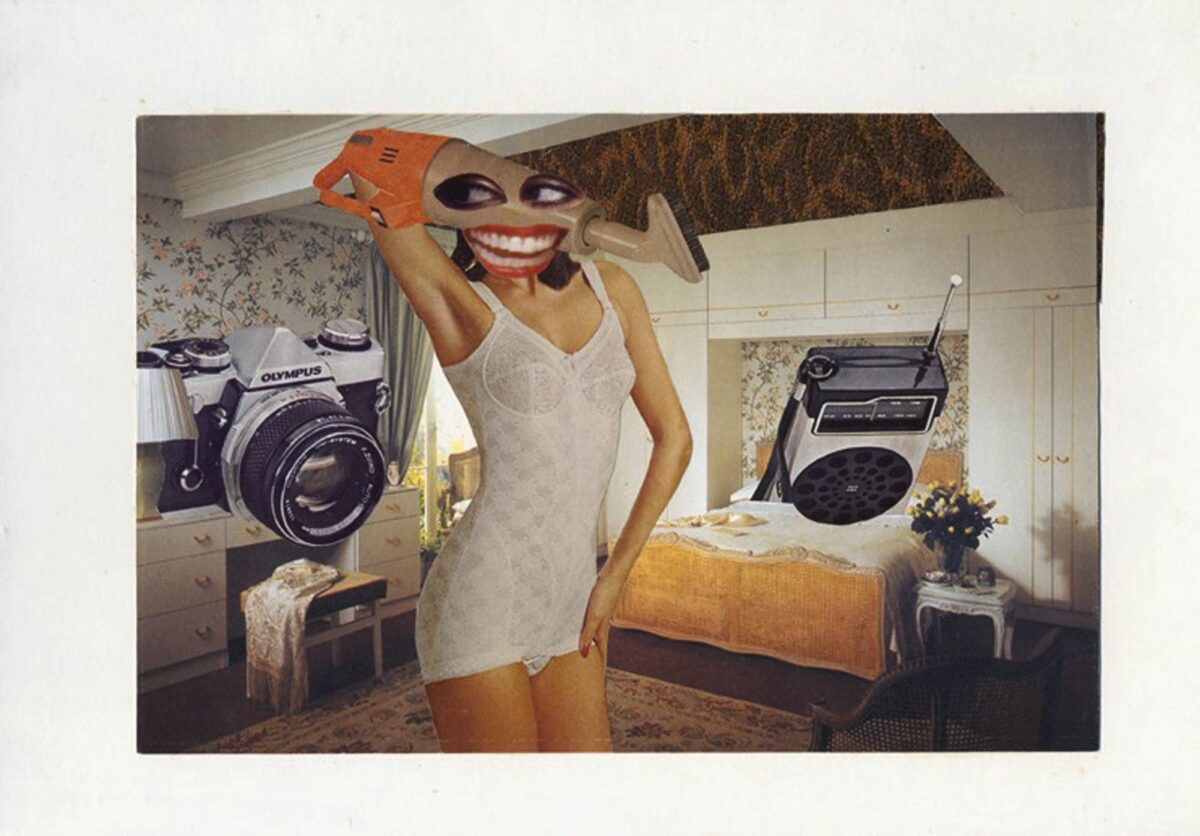

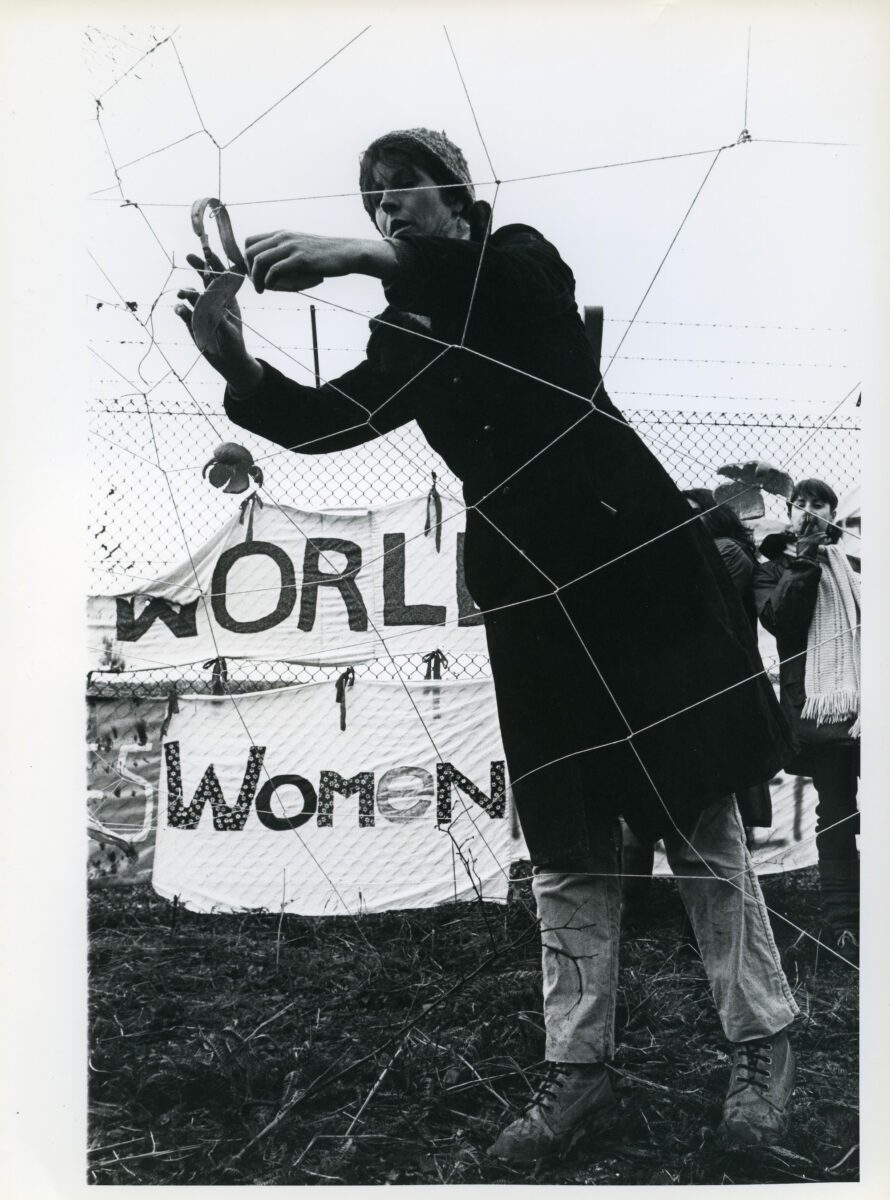

Both Re/Sisters and Women in Revolt are retrospectives that highlight aspects of feminist protest art, a genre not generally represented in major museum shows. While Re/Sisters explores the relationship between gender and ecology through works by 50 artists from across the globe and spanning several decades, Women in Revolt specifically puts feminist art in perspective of British society from 1970 to 1990, with works by more than 100 artists from Britain alone.

Both shows share sections on the women-led anti-nuclear protests at Greenham Common as an example of feminism reaching beyond obvious ‘women’s issues’ and beyond national borders. They also serve as examples of exhibitions that not only showcase feminist art, but that were curated following feminist principles by taking a more collaborative and non-hierarchical approach. As do they demonstrate the intersection with environmental issues not only through the art on the walls, but by placing sustainability at the core of the project: Re/Sisters was built with materials reused from previous Barbican exhibitions while the layout at Tate Britain was left unaltered from a previous exhibition for Women in Revolt. With their DIY aesthetic reminiscent of the schools or community centres where much of the work would have originated, display cabinets and panels add to the authenticity of the exhibition, while undoubtedly helping to stay within a much humbler budget than the Pre-Raphaelites that immediately preceded it.

While true gender parity and diversity may yet be out of reach for museums with immense collections amassed over centuries, the curators at institutions like the Barbican, Hayward Gallery or the Serpentine are free from such art-owning restrictions. The Serpentine in particular sets a precedent with a 2024 programme of exhibitions by artists across generational, ethnic and gender divides while also responding to advanced technologies and environmental emergency – kicking off on 1 February with a solo exhibition by feminist pioneer Barbara Kruger.

This year I won’t be travelling to Venice, but I am still curious to learn how the first biennale directed by a curator from the Global South will be received; provocatively themed ‘Foreigners Everywhere’, the 60th edition emphasises artists from historically marginalised backgrounds.

Gilbert & George (in)famously responded to being ignored by the Tate in favour of ‘all black art, all women art, all this art and that art’ by opening their own museum. Most contemporary private art museums I can think of were founded by white men to show off their collections, most notably Charles Saatchi or Damien Hirst. Tracey Emin and Yinka Shonibare took a different approach by building art spaces to nurture the next generation of artists in Margate and Lagos respectively.

A relatively new kid on the block with just 15 editions since its inauguration in post-war Germany, documenta shook up the art world by breaking with hegemonic institutional structures for its 2022 edition by appointing a Southeast Asian collective as curatorial team. What should have been celebrated as a template for a decolonised art institution was overshadowed by an anti-Semitism scandal that seemed to foreshadow the current political paralysis brought on by the Gaza-Israel conflict.

Addressing decolonisation since 2002 and the appointment of its first non-European curator, and increasingly experimental curatorial concepts since, documenta 15 adapted the Indonesian principle of lumgung, a radically collaborative approach to resource building and equal sharing. Based on principles of solidarity and an international network of local, community-based organisations across art and other cultural disciplines, ruangrupa aimed to present ‘an agglomeration of ideas, stories, (wo)manpower, time and shareable resources’.

The result were workshop-like presentations with an emphasis on storytelling and collective learning. Space for shared meals, conversation and contemplation instead of collectable objects by blue chip artists. An overdue challenge to prevailing ideas of what constitutes a global art exhibition that overwhelmed the majority-Western visitors to the German provinces.

Back in the British capital, I look forward to the Royal Academy’s take on ‘art, colonialism and change’ with Entangled Pasts, 1768 – now, a major exhibition of contemporary and historic works. The announcement carries a trigger warning to alert visitors to ‘themes of slavery and racism, historical racial language and imagery’. Perhaps it is necessary to take a couple of steps backwards in order to move forward.

The process towards postcolonial museums has begun with institutions no longer presenting Eurocentric views of the world without recognising counter histories, conflicting stories and non-Western knowledge. I, for one, am keen to expand my vocabulary and will be looking out for examples of art as drivers of social change – not just in museums.

Some major shows announced by London galleries for the first half of 2024:

1st February – 17th March 2024, Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You, Serpentine South

3rd February – 28th April 2024, Entangled Pasts, 1768 – now: Art, Colonialism and Change, Royal Academy of Arts

13th February – 26th May 2024, Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican Art Gallery

14th February – 24th June 2024, Soulscapes, Dulwich Picture Gallery

15th February – 1st September 2024, Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern

22nd February – 19th May 2024, The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure, National Portrait Gallery

8th March – 2nd June 2024, Acts of Resistance: Photography, Feminisms and the Art of Process, South London Gallery

12th April – 1st September 2024, Yinka Shonibare, Serpentine South

16th May – 13th October 2024, Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920, Tate Britain

22 May – 1 September 2024, Judy Chicago: Revelations, Serpentine North

6th June 2024 – 26th January 2025, Zanele Muholi, Tate Modern