Matthew Collings has been an inspiration to me for many years and this interview has been a fantastic opportunity to cover his successful career in the arts.

I am not brilliant at watching TV, but I couldn’t wait for his documentary shows to come on. It was the highlight of my day, someone talking about art on national TV. He gave me a deeper understanding of the subject. He could talk about art in such a way that it made you step into the work and be with the artists. To want to be an artist yourself. As a writer he has an incredible gift at expressing the importance and meaning of works of art and delivering his knowledge with humour and ease. He speaks in a language that can be understood by all. He’s an artist as well as a writer. And altogether his writing, his paintings and drawings, and his presentations on TV, convey a sense of dialectic freedom. He creates fantastic geometric paintings based on patterns, with his partner, the mosaicist, Emma Biggs, which explore the use of colour – which he says is an often-overlooked element of art.

For the interview I revisited some of Matthew’s documentaries, for example, The Rules of Abstraction:

I am forever a learner watching these videos. I sat there looking at Kandinsky to Fiona Rae painting in motion. To witness two artists mark-making with paint was an absolute joy. I learnt of a new artist, Hilma Af Klint, an incredible abstract female painter who died in 1944 and until recently was almost entirely unnoticed. Matthew picks up on the beginnings of Kandinsky stumbling onto to abstraction, which Kandinsky explained once in a book. It may have been that he didn’t recognise his own painting, one day, Matthew says in the programme — as it lay on its side against the wall. Kandinsky’s fascination with the shapes and colours he saw at this moment, without knowing what they represented, pushed him into a new art language. Matthew is a master at sharing these magical insights.

His books include: Blimey! From Bohemia to Britpop: The London Art World from Francis Bacon to Damien Hirst; It Hurts: New York Art from Warhol to Now; and Art Crazy Nation – all published in the late 90s, early 2000s by a company called 21 founded by David Bowie. Artforum called Blimey! “the most popular art book ever.” He wrote Matt’s Old Masters: Titian, Rubens, Velázquez, Hogarth for Wiedenfeld, in 2003 (also based on a Channel 4 series). His book on Sarah Lucas for Tate Publishing, 2002, was praised in Artforum by feminist art writer, Linda Nochlin.

Video downloads of almost all Matthew’s TV work over the years can be found on YouTube. It includes a BBC documentary on Willem de Kooning from the mid-90s; This Is Modern Art Channel 4 1998; Hello Culture Channel 4 2001; Matt’s Old Masters: Hogarth, Velázquez, Rubens, Titian Channel 4 2002; Impressionism: Revenge of the Nice Channel 4 2003; The Me Generations: Self Portraits Channel 4, 2004; This Is Civilisation Channel 4, 2008; What is Beauty? BBC, 2008; Renaissance Revolution: Raphael, Piero, Bosch BBC 2010; Beautiful Equations BBC4 2012; Turner’s Thames BBC 2012; The Rules of Abstraction BBC 2015

As a major artic critic in the UK, I am aware you gave Jeff Koons his first exposure on British TV. What did you think made him successful as an artist?

He was interested in what makes people tick psychologically, their hidden desires, and he tried to find an expression for it that wasn’t already a convention in art. By the way, I don’t think of myself as a major art critic at all.

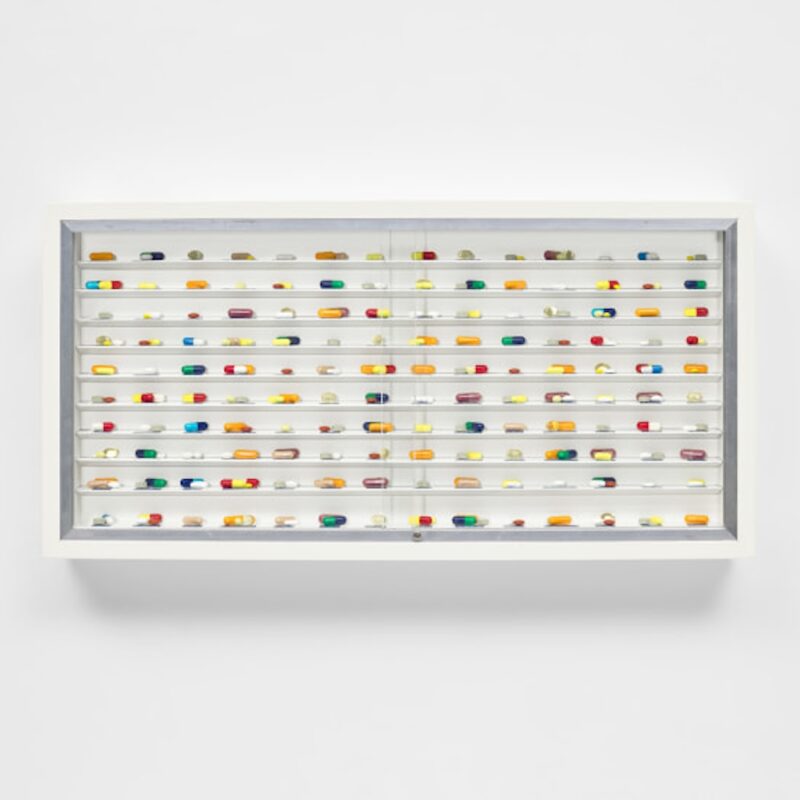

You also successfully exposed Damien Hirst for the first time to a TV audience. Did you notice any common drives and similarities been Hirst and Koons? What were the differences?

They’re very different artists ultimately but they were each clever at coming up with objects capable of endless metaphorical readings. But Hirst seemed to me like someone who would do anything to succeed, based on already existing models of success (which included Koons, particularly his basketballs in vitrines). Koons by contrast had a particular concern: desire, as it’s assumed to be in the forms of popular culture, particularly advertising. And that was his medium, in a way, which he transformed into compelling objects. I think Hirst is more like a sort of uneven and chancy version of advertising.

Thinking about your documentary on Georgia O Keeffe, made for the BBC and directed by Vanessa Engle, how do you think women are positioned in the field of painting currently?

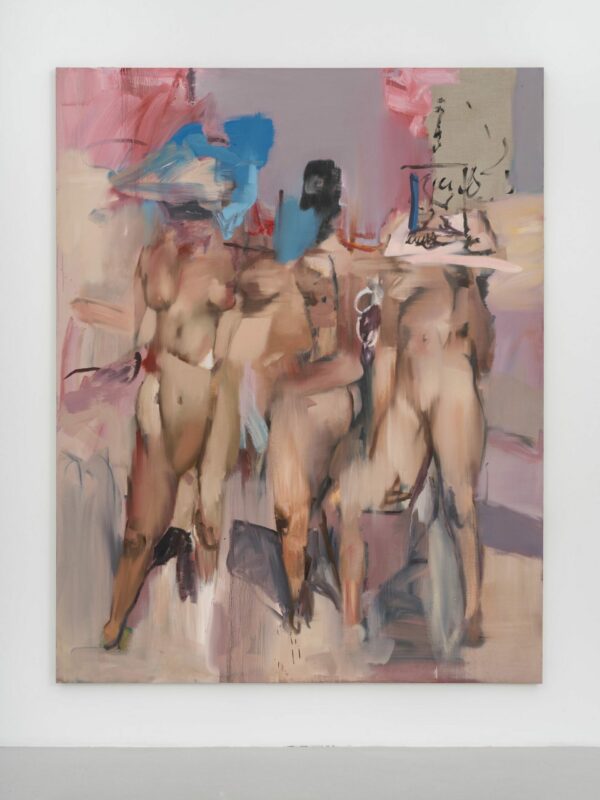

Well of course much better than the period when she first emerged, a century ago, and better than when that BBC film was made. But even at that point, there had been a big change towards women being accepted as art stars, not just men. A difference now that I personally find very striking is women painters. Ones of this moment and historical ones. The latter category, people like the mid-twentieth-century New York painters — Joan Mitchell, especially — seem fantastic now.

Your brilliant London art-world chronicle Blimey! has been one of the best-selling contemporary-art books. What inspired you to start writing this book?

Personal experience. Like someone writing a novel. It was about art-culture in London in two different periods. I had a sense of a vanished world replaced by a new one, and a sort of moral and aesthetic massive disconnect between them, even though the more recent one was often sold in terms of values intrinsic to the older one. That older one was serious but maybe could be thought of as provincial: the London scene of the 50s and 60s. The newer one, the 90s art scene, wasn’t serious. But it was genuinely the new dominant thing. In reality though it was much more provincial than the other thing. London-based 1990s art was considered powerful and glamorous because of its elements of money and scandal, and a mass media willing to publicise it.

So, this contrast was my subject. I was born into the old scene. That was the art-world of my mother’s time (she went to art school). I became well-known during the 90s when I was in my 40s. I was already old. I’d done a lot of TV work already, and edited an art magazine, but it was in the 90s I became this figure associated with art as scandal. The most important ambition with that book was the voice. I wanted to write something that was literature, not the normal art book by an art historian. It was a comedy.

What advice would you give to anyone thinking of writing a book?

Have something to say.

What advice would you give anyone entering the world of being an art critic?

I never really thought of myself as one in the usual sense. They’ve usually studied art history. But I went to art school. When you’re writing about art but you’re untrained in art history – that is, you don’t have any discipline as a thinker and you’re just going on your instincts – then my advice is always try and have a thought to start out with that you’re clear about and find genuinely meaningful. Then whatever language you can cope with, is OK. Content, if it’s genuine, will always be convincing. But just imitating the sound of art-writing is a drag in my view. I mean, as a reader it’s horrible. That’s what most people encounter when they read the art columns in the papers. Or listen to art stuff on the radio or watch art programmes on TV. That’s why art writing isn’t considered a marvellous genre on the whole.

The Channel 4 TV series This is Modern Art which you wrote and presented, won a Bafta among other awards. What do you think your strengths were that this award recognised?

You never know with awards, they’re always arbitrary. It was a really well-made series, with clever directors and a clever overall producer, Ian McMillan. The budget for it was high, for those days. The language I used as the presenter: the commentary I wrote, and I the kinds of things I said in front of the camera, walking around in front of art works, wouldn’t be tolerated now, because TV culture has become much narrower. Really it was an extension of Kenneth Clark and Robert Hughes: they did their own thing with “Civilisation” and “The Shock of the New,” and I did my own thing with “This is Modern Art.” Since then, art presenters are forced to fit into formulas that the TV producers themselves are forced to fit into by the TV programmers, based on analysing ratings figures. There’s no spontaneity. No one’s original. The Channel 4 people were excited by the way I talked, because they thought it might be truly popular. I think the award was because the series got a lot of press attention. It didn’t actually get high ratings figures. But it was considered ground-breaking. Anyway, my language was knowing but not up on stilts. There’s a lot of humour in the series but it always comes organically from the artistic ideas the series deals with.

The follow-up series to This Is Modern Art, which you also wrote and presented, was about the Old Masters. With your own painting do you get any inspiration from that kind of art?

It’s my main inspiration. I mean the ideas I have are rooted in the right now moment. But how to paint always comes from the past. And that particular type of painting which the series was about, where there’s an emphasis on the movement of the brush, and the paintwork is very animated, is important to me.

The word Master is male. Why do you think there was a lack of female Master painters?

There were women painters but the reason they haven’t received the acknowledgment that Rembrandt receives and the reason not so many have been up on the same level as Rembrandt, is the same: purely societal. Women were kept down. You can’t get good at something if you don’t get a chance to do it. Women weren’t given that chance. They were forced to serve men. Art isn’t a matter of talent alone but talent plus experience. It’s changing so rapidly now the contrast is amazing. The most exciting painters at the moment are equally men and women.

Following on from your BBC2 programme School of Saatchi a reality TV show for newly trained UK artists, what advice would you give in this current climate, after the pandemic, for young creatives to flourish in the art-world?

I would feel uncomfortable generalising. Be brave and free! I couldn’t care less about the art world so I may be the wrong person to ask about this: I mean, the flourishing side. I’ve never written about the art world to encourage people to get into it. If anything, it was to highlight the embarrassments of being in it.

If you had to say one art movement was your favourite, which one would you chose and why?

Not a movement. But a steam of making through the ages: the type in that series you mentioned. Painting where the making itself is very apparent and almost a subject on its own regardless of the depiction element. I’m totally capable of getting into every kind of art under the sun. But that type is my personal interest.

Do you prefer writing to painting?

No, the opposite. Not that I find it a holiday. It only becomes good if it’s real work.

How do you organise your time?

I haven’t got any routines. I do everything at different times every day. I often have periods where I do everything at night, in fact. I just drift into work – I drift out of laziness and distraction, and into work. But the things I do when I’m lazy and distracted, like watching movies and drama TV series, probably feed a bit into my work: I like to see how content is structured.

What makes you tick?

I’m 65. I’m happy to have survived so long by just trying to do what I want, so I suppose that’s what makes me tick: the drive to only do what I want to do. Usually, you can only do what you want if you’re incredibly wealthy. But I was born into extreme poverty, so I don’t know how I did it.

Your wife, Emma Biggs, is also an artist. You’ve curated shows together. And you work alongside each other as artists making a fantastic team. What makes a solid successful creative team?

A sense of each other’s gifts and limitations and a clear idea what it is you jointly want to accomplish.

I know you have jointly done curating work together. What are your favourite exhibitions you have curated together and why?

We liked curating a show of Picasso’s late 50s paintings for Helly Nahmed, a few years ago, based on Manet’s Dejeuner sur l’herbe. Our idea was to de-emphasise the element of Picasso’s mythology as a mysterious genius. We concentrated instead on his reduction down to very elementary shapes. We chose the pictures that allowed this point to come across.

When painting what do you want to convey to the viewer?

I want to be free and funny in my solo work. In the collaborative paintings, I do with Emma Biggs, our aim is to make something dynamic that you can go on looking at, with a feeling that it’s always changing. You see new rhythms in it all the time.

Do you draw out plans when starting a new piece or series of works?

No, I just pile in. In our joint works we draw out the pencil grid first, on the canvas. But after that it’s spontaneous and intuitive, we don’t have a system.

What importance is colour in your work? How do you think it is represented in other contemporary painting? Have you got a favourite artist that successfully explores colour with painting?

In the drawings I sell on Instagram, colour seeming to be vibrant is an important effect I’m always attempting to achieve. It’s not a matter of the colours being full strength. But orchestrating bright and muted areas into a colour unity. On the other hand, with these works animated spaces and animated figures and objects, are important too. With my collaborative paintings with Emma, colour arrangement is really the only thing. There’s nowhere else to go for the viewer. I don’t have favourite colour-successful artists, no. I can’t ever think of an artist without thinking of loads more at the same time. Across time, colour is as great in cave art as it is in Quattrocento Sienese painting, in Titian, in Indian miniatures, in the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists and Abstract Expressionism and Colour Field art. There’s no development in the sense of progress. When an artist accepts colour is a thing, that’s when it’s good. And good means successful expression of delight in reality via colour.

Have you got successes and failures as a painter and what are they?

My personal solo work: the failures are to do either with overconfidence or the opposite, timidity. With the joint work, we don’t allow any failures. With colour generally in contemporary art, there are some great colourists: Dana Schutz, for example. But I don’t think much contemporary art is particularly about getting the most out of colour.

What do you feel were the most successful moments in your career? What were the most challenging moments? How did you overcome the most challenging parts of your career?

I enjoyed editing an art magazine. It’s things I enjoyed doing which I consider to be the successful career moments. I never had a career in the usual sense, where you set out to do something. I fell into things. Not having a career is the whole point of being free. Fuck careers — but do try to be fulfilled somehow. Being with your own children and grandchildren isn’t a relief from a career, it’s part of the true career of a fulfilled humanity, as Marx said. I’ve often changed jobs, and for a brief, while that can be challenging as you suddenly go back to being poor and not having any power. But then I find something I like doing and I forget about having been challenged.

What are you currently working on or towards?

A book about art history based on drawings I do of people and events from art. It’s not a rigorous argument. It’s just attitudes I have. These drawings are in colour and they’ve all been sold already. They will be about two hundred in the book. I’ve done many times more than that number, so there’s a lot to choose from. The reader will feel part of a chat buzzing in my head all time, going from artist to artist from quite different historic periods, from shamans in caves painting animals to ancient Greeks to Romantics and Expressionists and to artists alive now. A lot of enjoyable mental jumping around.