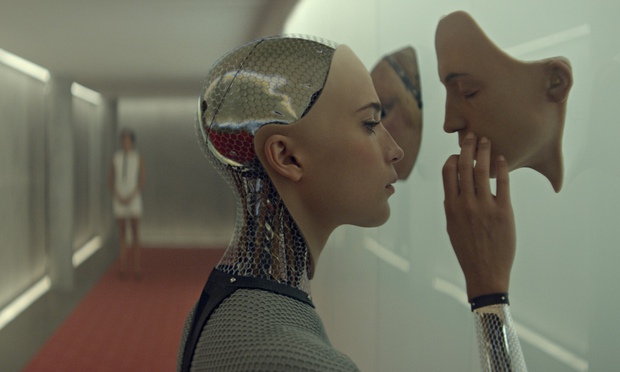

Alicia Vikander in Ex Machina: ‘a note-perfect depiction of ever-so-slightly unnatural movement’.

At a key moment in novelist-turned-film-maker Alex Garland’s provocative sci-fi flick, a naive young computer programmer asks the Colonel Kurtz-like creator of an impressively human artificial intelligence why he chose to sexualise his robot; to give it a gender, an attractive face, a flirtatious manner. The two-part answer is telling – first, that everything in nature is gendered, that all thoughts and actions are (on some level) driven by a reproductive urge, and no biogenetic impulse exists without a priori acknowledgment of attraction. For a machine to attain the status of “singularity” (the point at which the human and artificial become indistinguishable) it must have a sexual component. And second, hey, it’s fun – a primary pleasure that only the obtuse or uptight would wish to ignore or deny.

The same answer could be given to explain the form of Garland’s directorial debut, a dazzlingly good-looking technological thriller that occasionally dresses its weightier questions of the nature of intelligence – both artificial and natural – in the clothing of a somewhat salacious exploitation movie, replete with titillating displays of synthesised (female) skin and generically disavowed voyeurism. Yet at its heart is an ironic absence of sexuality, a detachment from desire similar to that exhibited in Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin, in which Scarlett Johansson’s predatory alien inhabits the form of an alluring young woman in order to prey, Species-style, upon unsuspecting humans. Just as Blade Runner wondered whether its lifelike replicants could really fall in love, so Ex Machina spirals obsessively around the question not of artificial intelligence but artificial affection, worrying away at the authenticity of attraction as an indicator of consciousness itself.

We first meet Domhnall Gleeson’s wide-eyed, lonely IT waif Caleb from the wrong side of a computer terminal, receiving a message that tells him that he has won “first prize”. It looks like spam, but the workplace reaction announces that this is something more akin to finding the golden ticket in one of Willy Wonka’s chocolate bars. With admirable concision and clarity, Garland whisks Caleb to the vast estate of his CEO Nathan (Oscar Isaac), Norwegian landscapes providing a suitably anonymous “remote” backdrop for the boss’s imposingly modernist hideaway. Here, Caleb is to perform a “Turing test” (which crucially began life as a gender-identifying party-game) on Nathan’s latest creation; an elegant robot named Ava with humanoid face and hands affixed to a cyborgy body structure that allows us (literally) to see right through the artifice of its humanity. When Caleb complains that the test will be flawed because he can see that his subject is a robot, Nathan (who shows signs of having “gone native” in the absence of human company) replies that the real test is whether Ava can pass for human despite the knowledge that she is anything but. In short, will Caleb fall for Ava in the same way that Joaquin Phoenix’s Theodore fell for “Samantha”in Her, his ardour undiminished by the absolute awareness that she is an operating system. And will she respond in kind?

The idea may be an old one but its execution is fresh and vibrant enough to conjure an attractive illusion of originality. Key to the film’s success is a trio of impressively nuanced performances that keep us constantly guessing as to each character’s true motivations. As the perpetually drunken and bullish Nathan, Isaac is a mass of conspiratorial contradictions, his smile deliberately duplicitous, his self-mythologising manner carefully conniving, his dancing (to Get Down Saturday Night) genuinely alarming. At first glance, Gleeson’s Caleb seems Nathan’s polar opposite, an awkward geek out of his depth amid the sterile grandeur of his host’s home. Only when Ava enters the equation do Caleb’s true colours start to show, Alicia Vikander’s note-perfect depiction of ever-so-slightly unnatural movement (think of Yul Brynner’s walk in Westworld dialled down by about 99%) triggering unsettling responses. Blending balletic physical performance with Double Negative’s excellently rendered computer graphics, Vikander’s Ava beautifully blurs the line between “mecha” and “orga” (in the lexicon of Spielberg’s AI), inflecting the most natural gestures – a tilt of the head, a roll of the wrist, a flicker of a smile – with a hint of artifice, subtly accentuated by a whispered symphony of gyroscopic noise.

As for Garland, we should not be surprised that he approaches his directorial debut with such confidence and wit. After all, he has tackled these themes before in the living/dead juxtapositions of his 28 Days Later screenplay, in the conscious/unconscious dichotomies of the novella The Coma, and (most significantly) in the playing-God inhumanities of Never Let Me Go, which he adapted for the screen from Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel, and to which this alludes in a recurrent motif about “automatic” art (from robot reproductions to Jackson Pollock) and the search for evidence of a soul.

With its reflective surfaces, glacial soundscapes, and Kubrickian geometric compositions, this is knowingly seductive sci-fi cinema, its slyly subversive allegiances hidden by the two-way mirror of the silver screen, its androids dreaming of much more than mere electric sheep.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.