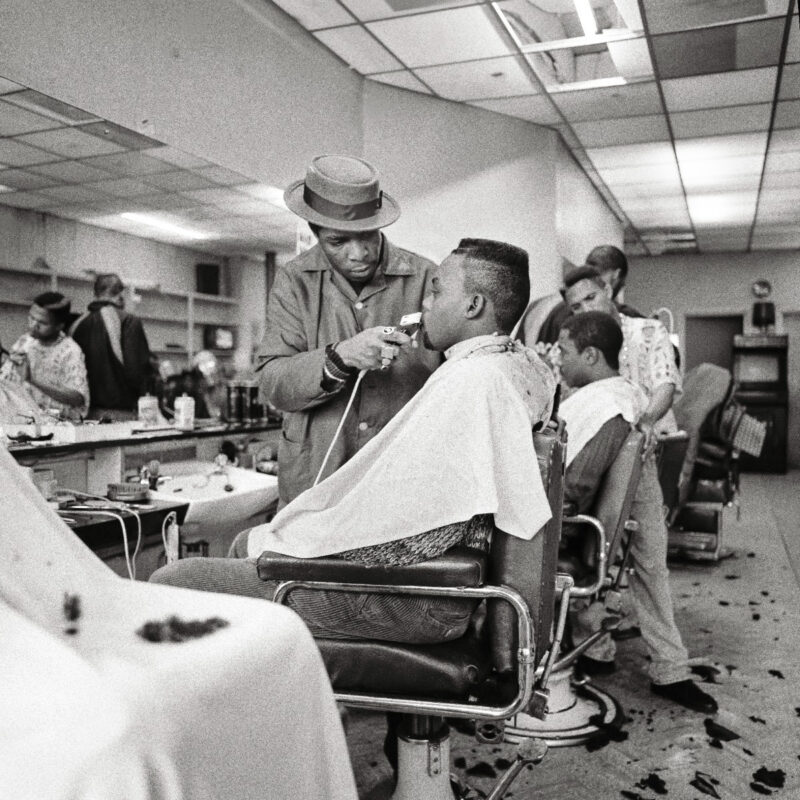

Hold it right there: David Hockney’s Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, 1970-71 during its rehang at Tate Britain last week. Photograph: Graeme Robertson

A new Tate Britain opened last week – not that the old one was ever fully closed, just partially boarded up by the gallery. After almost two years it’s now possible to walk right round the museum and see the history of British art unfold before your eyes. That is the main claim, at any rate, but while the much-touted return to chronology cannot be denied – the start date of 1540 is set in gold on the floor, the final works are contemporary – the principle is only as valuable as the practice and there is still, alas, some strangely mixed curating at Millbank.

The new museum gets off to a superb start (as it always did) with the Tudors and Stuarts, including a terrifically powerful portrait of a thuggish young lord, fist to waist, filling the frame, painted at the same time as Holbein’s Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling on loan from the National Gallery. Works by other resident aliens – Marcus Gheeraerts’s bare-thighed Captain Lee, Daniel Mytens’s beautifully sensitive portrait of the Earl of Arran in scarlet stockings and silver gloves –remind us that so much great British art is not by British-born artists. Look out later for the tragic paintings of the Polish refugee Josef Herman.

The 18th century has a touch of the National Portrait Gallery about it – Hogarth’s deathless portrait of his servants’ serious faces alongside Gainsborough’s flighty aristocrats, Joseph Highmore’s ever-popular Mr Oldham and His Guests amiably supping their negus in the firelight – though perhaps the National Portrait Gallery could have loaned some masterpieces for the occasion. Romney, Reynolds and Lawrence, Raeburn and all the Scots in general are pretty poorly represented at Tate Britain.

Then it’s prize cabbages, hunting, shooting and fishing, dogs and picnics, days at the races and trips to the seaside: English art at its most parochial and anecdotal, with occasional works by Stubbs, Constable and Turner. Gothic art is neglected, and much more significantly there is no place for one of the greatest of all British traditions – the graphic art of Tenniel, Gillray, Bewick, Cruikshank and Beerbohm. Blake will be the exception.

The Victorians are hung three-deep like a jostling 19th-century salon, though the pre-Raphaelites can look after themselves. But a little gallery of fragile works on paper, including an aqueous blue cyanotype by Anna Atkins, the world’s first woman photographer, and Georgina Macdonald’s elegiac watercolour of a dead bird from 1857 (women artists are exceptionally well represented), makes one realise just how relentlessly crowded the grand galleries have been. This side of Tate Britain just doesn’t have enough intimate rooms.

The 20th century, on the other side, opens with not one but two spaces devoted to the muckle works of Henry Moore. Still, they give way to a brilliantly grouped selection of political images by Peter Kennard, Nigel Henderson, Don McCullin and Colin Self. Jack Yeats, Christopher Wood, Paul Nash and Edward Burra all get their due, and the whip through the past 30 years is as representative of the British art scene, more or less, as Tate Britain’s own Turner Prize exhibition, from Howard Hodgkin and Gilbert & George through to Sarah Lucas, Mark Wallinger and Richard Wright.

It is nobody’s fault that these are far from the strongest works by these artists. Museums have scarcely been able to compete with private collectors in a hyperinflated market for several decades, but still a few more loans would have helped. On the other hand, these galleries are not configured for contemporary media as they might have been.

Wallinger isn’t represented by any of his tremendously inventive film works, for that would have involved darkened rooms or at least monitors and headsets. Instead, Tate Britain is showing an early wall-work from 1985, Where There’s Muck, which collages different kinds of political representation from Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews sitting smugly before their landscape to poster, banner and spray-painted slogan. Hard by hangs a Hodgkin, its swaths of paint juxtaposed with this graffiti to the least sympathetic effect.

And here in a stroke is one of the problems at Tate Britain. The broad chronology is all there, but the presentation is too often unsympathetic to the individual works.

To ram home the point that very different kinds of art were being made in Britain at exactly the same time (is this news?), Gwen John’s luminously quiet and solitary self-portrait is forced into the company of two brash portraits of women by male painters simply because they were all made around 1900. It’s the visual equivalent of a voice lost in the noise.

A lyrical abstract by Bridget Riley is positioned next to one of Anya Gallaccio‘s fatuous arrays of rotting blossoms for the same date-based reason. The subtle optical effects of Riley’s high-chrome painting are undermined by Gallaccio’s wall of dank flowers, which interfere with the viewer’s peripheral vision.

Worst of all, Samuel Palmer is hidden in a dark and narrow space behind a door, as if nobody really wanted him to be there.

The great emphasis on sculpture that has been apparent since Penelope Curtis took over as director of Tate Britain proves troublesome too. Where to put all these figures and forms? Anthony Caro’s huge Early One Morning blocks Francis Bacon’s Triptych to the point where both are undermined (struggle to see round or through the Caro and it becomes a structure, not a sculpture).

Whistler’s touchingly subtle portrait of the little girl Miss Cicely Alexander – otherwise known as Harmony in Grey and Green – is shoved in a corner and then further obscured by a kitsch Victorian statue. The nude youth yawns and stretches in erotic languor as if he were doing it just to annoy, deliberately getting in her way.

Stubbs, Gainsborough, Hogarth, Whistler – their paintings are scattered all over the place, so that you can never get a true sense of their stature or development. Perhaps this is a useful way of concealing the patchiness of Tate Britain’s historic holdings; Mr and Mrs Andrews, The Shrimp Girl, Whistlejacket, Rain, Steam and Speed: so many masterpieces are at the National Gallery.

Still, William Blake has a miniature museum to himself, containing all the great works, upstairs in a one-off gallery. You can enter via the garden, rather aptly, without having to go through the main galleries.

Arguments about Tate Britain since its separation from Tate Modern have tended to focus on the wall texts and the pick-and-mix thematic displays. These still exist, incidentally: one is currently devoted to landscapes. The main historical hang runs through the perimeter galleries.

About the labels, I applaud Curtis’s decision to place them below the paintings, angled so you only have to dip your eyes momentarily for titles, dates and artists’ names. All the emphasis is on looking, and not reading your way round the walls (get the headphones, the hand-outs or the new Tate Britain Companion if you want more context). But right now, this emphasis on looking remains somewhat rhetorical in congested or ill-assorted galleries where you can’t properly see all the art on display.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.