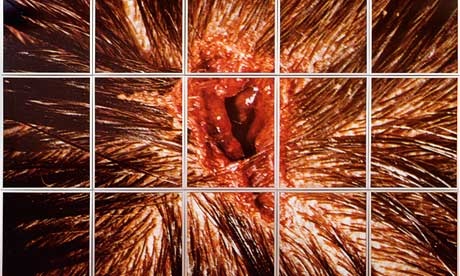

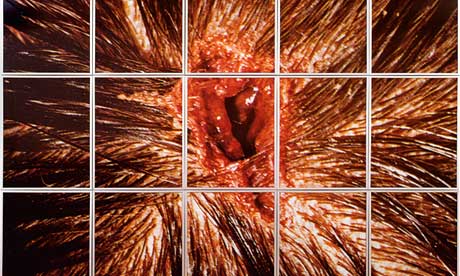

Collishaw’s best-known early work, Bullet Hole (1988). Photograph: Courtesy of Mat Collishaw and Blain|Southern

A pink lobster rests on a glistening metal platter, surrounded by furrowed brown clam shells and black-eyed, gossamer-legged shrimps. A hunk of bread and a glass of amber liquid complete the still life. Set in a pool of deep shadow, the mutely lit objects in this photograph by Mat Collishaw beautifully resemble foodstuffs painted by some Dutch artist in the age of Vermeer. You might expect to find such a picture hanging in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. But the calm conceals a terrible truth: we are looking at a reconstruction of the last meal of Allen Lee Davis, who was executed in Florida in 1999.

Davis was convicted of a brutal crime: in 1982, he murdered Nancy Weller and her two young daughters, Kristina, nine, and Katherine, five, in Jacksonville, Florida. But his own execution became a grisly farce when the electric chair failed to deliver the clean death it was supposed to, and witnesses heard him scream and saw him bleed. It was the last time the electric chair was used in Florida, which now prefers to end the lives of prisoners with a lethal injection.

For his last meal, Davis requested and got the banquet that Collishaw has reassembled and photographed to look like an Old Master painting: a lobster tail, fried potatoes, fried clams, fried shrimp, garlic bread and root beer.

Collishaw’s Last Meal On Death Row series is one of the eerily paradoxical works in which this powerful artist confronts beauty with horror. Other meals in the series are far more restrained. Karla Faye Tucker, who when she died in 1998 was the first woman executed in Texas since 1863, chose a healthy final meal of fruit and salad. Collishaw has pictured it in a sombre light that deliberately recalls paintings by the 17th-century Spanish religious artist and still life master Francisco de Zurbarán. Tucker had converted to Christianity in prison. Collishaw gives his imagined picture of her last meal a spiritual intensity.

In his studio in a converted south London pub, Collishaw is remembering his own religious childhood. His parents are members of the fundamentalist Christadelphian sect, and he grew up in Nottingham in a strictly regulated household where Christmas was not celebrated – he got no presents – and TV was forbidden. “I get on with my parents now,” he says, “but those kinds of things were difficult.” Once, he recalls, “I came home to find my dad burning all my copies of the Face.”

This childhood helps to make sense of his apparent compulsion to break rules, defy moral codes and, as it were, profane the host. Collishaw is an artist of risk and menace, whose work takes its audience to some very dark places. Once there was a name for this kind of provocative imagery: we called it Young British Art.

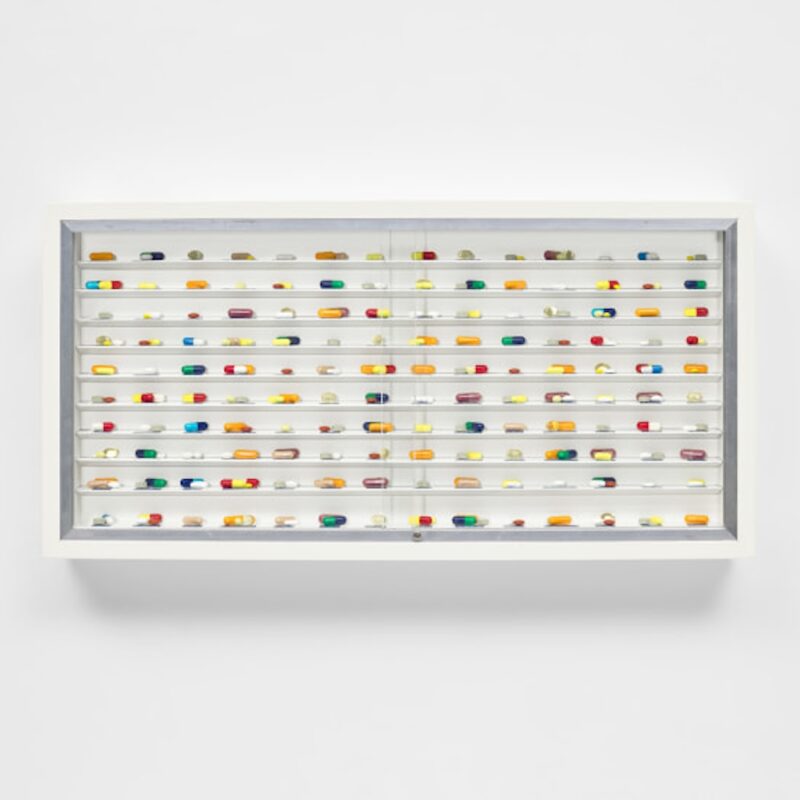

Collishaw is one of the YBAs, a name coined in the 1990s for a generation or a school or just a gang of artists who were then becoming internationally celebrated. He is a hardcore original YBA whose most famous early work, Bullet Hole, appeared in the exhibition Freeze that his friend Damien Hirst curated in a docklands warehouse in 1988. It is a massively enlarged photograph of a bullet hole in a human head, seen as a purple-lipped orifice surrounded by greasy hair. Through the giant hole you see darkness. Again, there is a religious echo: it is like one of the wounds of Christ in a painting of the Passion. Not that anyone noticed at the time, when Young British Art was tabloid headline, shock-horror stuff and its deeper meanings were rarely considered. Even by people who acknowledged it had any.

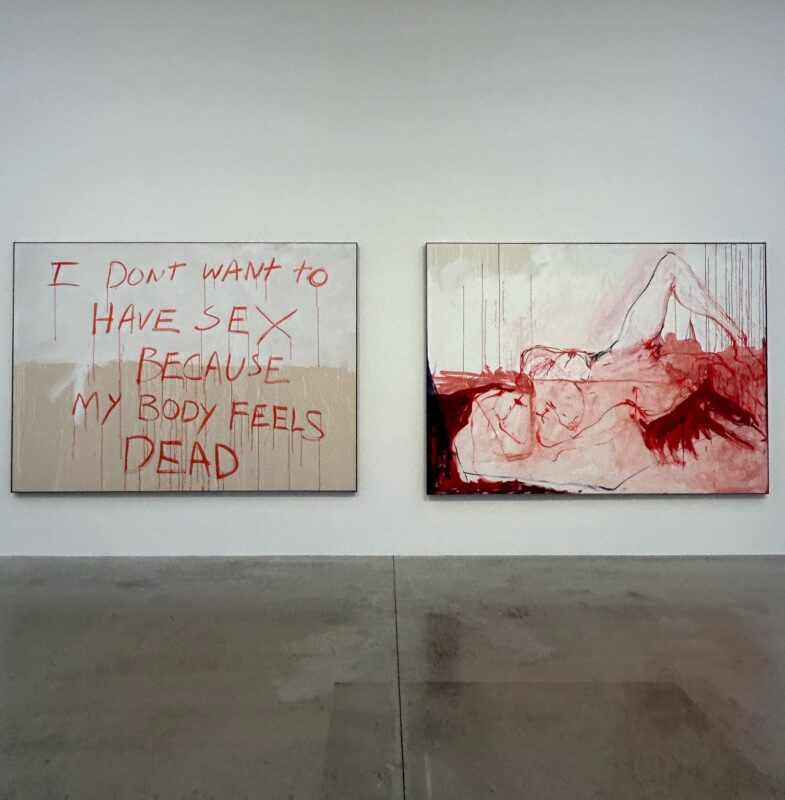

Collishaw flitted in and out of the tabloid version of the new British art. He was Tracey Emin‘s boyfriend, as well as one of Hirst’s best pals (as he still is: Collishaw recently took up painting after Hirst gave him 10 huge boxes of paint). And, of all the YBAs, he did project the image of being young, wild and a bit of a romantic. He photographed himself bare-chested in a pond on Clapham Common, trying to catch fairies. He posed as Narcissus gazing in a puddle (not so much recreating a Renaissance painting as restaging the cover photograph from the Smiths’ single This Charming Man). A raw, urban romanticism, a whiff of youthful daring came off his art.

And now he is in his 40s.

I owe Mat Collishaw an apology. In 2009 I sat at a boardroom table in Tate Britain discussing who should be shortlisted for the Turner prize, as one of that year’s jury. I suggested Collishaw, who was still young enough – Turner Prize artists have to be under 50 – and in my opinion getting better all the time. I thought he deserved to be shortlisted for a series of photographs of butterflies crushed and smashed and seen apparently at the moment of their deaths, enlarged into great gaudy smears of colour. What haunting images of beauty and ruin, life and death. But one fellow juror said this could happen only if we created “an all-YBA shortlist”, the last hurrah of the movement that made British art famous. In the thinking of the art world, the Collishaw generation are the establishment now and their stuff is old hat. Sensation and shock are dirty words, crude populism frowned upon now that modern art is the favourite entertainment of the well-heeled middle class. Art now, apparently, is more subtle than it used to be, as are our souls. The mind of visceral art that drew crowds to Sensation! at the Royal Academy in 1997 is judged too brash and loud.

I lost the argument. So no Turner for Collishaw.

Instead, he has a retrospective about to open at the Arter Foundation in Istanbul, a show that foregrounds his political conscience in powerful works such as Last Meal On Death Row. For me, Collishaw is a good political artist for the same reason he is a good religious artist and a good artist-artist. It is because he believes in the efficacy of images. Not for him the abstract evasion, the minimalist half smile – fashionable or not, he wants to punch your imagination in the stomach. He justifies the art of sensation by showing how it can have depth in its oomph.

He is very articulate on the subject, as we chat in his studio while looking through drawers full of Insecticides, the pictures for which I wanted to shortlist him for the Turner. “Shock makes us feel more alive,” he insists. Sure, back in the 90s, “Some people were using shock art as a fuck-you-in-your-face kind of thing”, but for him shock is much more serious, and all his favourite painters from the past make use of it – “great art that I like when I go to the National Gallery, like Caravaggio and Rubens and Géricault and Delacroix.”

The book on his desk is a new academic study of the 19th-century French poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire – specifically, about his drug use. Baudelaire was surely taking drugs when he celebrated his favourite artist, Eugène Delacroix, whose paintings indulge in violent excesses worthy of any artist of today. Delacroix’s painting The Death Of Sardanapalus portrays a tyrant killing himself on a vast pink bed surrounded by his harem and slaves in a frenzied apocalyptic party. Its mood of dissipation haunts Collishaw’s art. In his photograph Burnt Almonds, he recreates a scene described by a Russian officer in the ruins of Berlin in 1945: a Nazi officer and his mistress lie dead, having taken poison in the middle of a last decadent party. In a new cycle of paintings that Collishaw has created – they are being finished by an assistant in the downstairs of the pub – he enlarges empty cocaine wrappers to suggest the decadence of the high-flying financial world on the eve of the credit crash.

His Nazi picture, he says, shows “a total corruption of beauty”. His use of shock always involves “seduction and beauty”. I am staring at the Last Meal Of Death Row pictures pinned on his studio wall as he says this. You can scarcely have a starker example of art that lures the eye, only to punish the mind with terrible knowledge. Other subjects he has eerily illuminated with installations and images that are at once beautiful and appalling include war photography, Victorian child prostitution and, most recently, the portrayal of poverty. His Istanbul exhibition includes the premiere of a video in which he stretches photojournalist Kevin Carter’s famous image of a child apparently being stalked by a vulture in the Sudan famine in 1993 into an event that happens in time, in slow-motion. By animating Carter’s shot, he wants to question the way we take pictures at face value – this image became controversial because some said Carter should have intervened, and he responded by telling contradictory stories about it. Soon after winning a Pulitzer for this perfect press photograph, Carter took his own life. “He couldn’t make another image that gave him that buzz,” Collishaw says.

In the basement of his pub, we encounter a couple of mangy stuffed animals; Collishaw lives with taxidermist-artist Polly Morgan, and they are currently showing together in an exhibition in Walsall about contemporary art and nature called The Nature Of The Beast. Of all the images with which he seduces and confounds the onlooker, Collishaw’s flowers are his most beguiling and disgusting achievements. He has been experimenting with flowers since the 1990s, breeding – he claims – hybrid blooms that attest to genetic mutation. His Infectious Flowers started as photographs and have recently been realised as monstrous sculptures. “I make a beautiful flower,” as he puts it, “and then I have to go and infect it with venereal disease.” Black sores well up on pink petals, and in his 2012 sculpture The Venal Muse: Fenside, orchidean blooms have turned into gory pustulating columns of suppurating flesh. Nature produces monsters, and life evolves into corrupted versions of itself.

Collishaw placed his venereal flowers instead of bouquets at the entrance to his recent exhibition about the madness of the bankers on the eve of the crash. His art is lovely and vile. It is an art of our time and it hits true, like a bullet in the head.

• Mat Collishaw is at Arter, Istanbul from 2 May to 11 September. The Nature Of The Beast runs until 30 June at New Art Gallery, Walsall

This article was edited on 29 April 2013. The original said that Collishaw was married to Polly Morgan, and referred to the Arter as a centre. Both have been corrected.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.