William Eggleston, “Untitled” (Woman Wiping Van, Queens, New YorK), 2002. Pigment print, (55.9 x 71.1 cm) 22 x 28 inches, edition of 7. Courtesy: Cheim & Read, New York. ©Eggleston Artistic Trust.

Cheim & Read present two concurrent photography exhibitions featuring, respectively, a selection of rarely shown photographs by Diane Arbus and new work by William Eggleston. The installation of Arbus’s work, shown here under the title “In the Absence of Others”, brings together a group of photographs of empty interiors and artificial landscapes spanning the 1960s. The Eggleston exhibition is titled “21st Century”. A presentation of this work is also on view at the Victoria Miro Gallery in London.

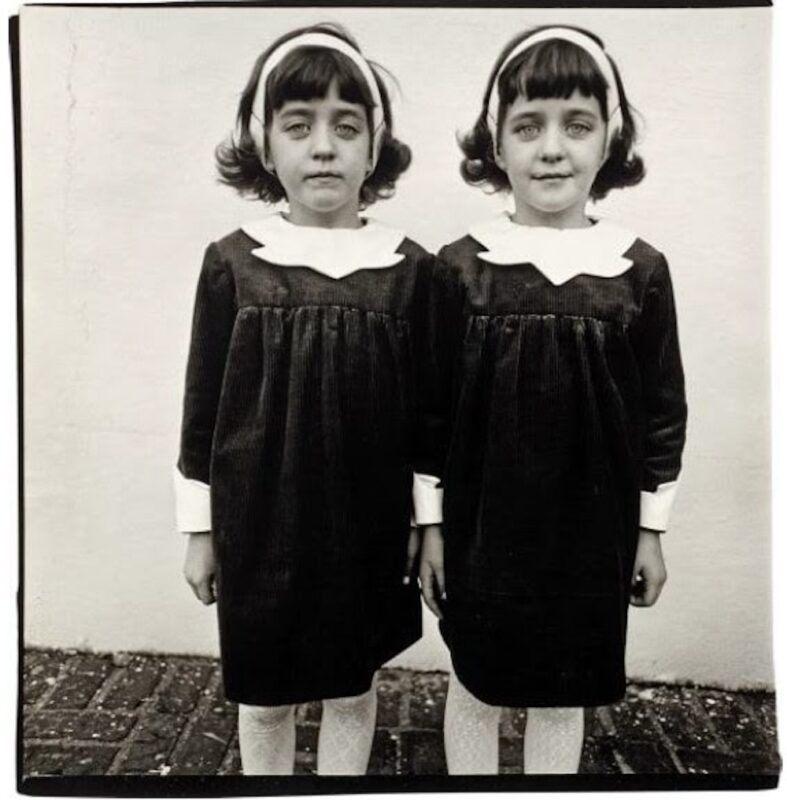

Born in New York City, where she lived and worked nearly all her life, Diane Arbus (1923-1971) is a celebrated master of the critical power of the photographic image and one of the most influential artists of the “20th Century”. Among her best-known photographs are unflinching black and white square format portraits of couples, children, middle-class families, carnival performers, nudists, transvestites, zealots, eccentrics and celebrities. Her deliberate attention to detail and her respect for the documentary power of the medium confront the viewer with disconcertingly intimate encounters they might otherwise have escaped entirely.

Due in large part to her inclusion in MoMA’s 1967 New Documents exhibition, organized by John Szarkowski, Arbus is associated with the generation of “street photographers” that included Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand. These photographers prowled the streets of New York, equipped with their cameras, always ready to capture on film the bizarre juxtapositions that, under the conditions of the modern city, could occur without warning, practically instantaneously. Arbus, however, rarely staked as much of her photographs’ poignancy on the super-fast flash of the chance moment as did the male photographers of her generation. Instead, her photographs so often appear to be carefully thought-out, almost meditative in their quiet stillness, regardless of the actual circumstances of their making. Where their work relies on speed and agility, hers depends on patience, diligence and an unerring sense for the timeless and the mythic embodied in bare fact.

This is especially true of the Arbus photographs that have been selected for the Cheim & Read exhibition, which are remarkable for the way they manage to convey intimacy, despite the absence of human figures. The building in “A castle in Disneyland, Cal.”, 1962, is pictured rising almost ominously from a moat of perfectly – unnaturally – still water, which mirrors the building with uncanny precision. The image is simultaneously romantic and ironic, a vision from a fairy tale discovered in a desolate empty amusement park. Like so much of Arbus’s work, the picture is full of paradoxes it refuses to resolve.

William Eggleston, born in 1939 in Memphis, Tennessee, is widely credited with having elevated the medium of color photography to the status of serious art. In the 1960s and 70s color photography was most commonly associated with such middle-brow phenomena as commercial advertising and the family snapshot, and only the black and white photograph was deemed acceptable for display in a museum or gallery setting. Indeed, Eggleston’s first one-man show at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1976, organized by John Szarkowski, marks the moment in the history of photography when color photographs were first admitted for exhibition to the ranks of a major museum.

Eggleston’s most recent photographs, exhibited here at Cheim & Read, give themselves over almost entirely to problems of composition, color, and texture; and yet they do so – remarkably – only within the confines of what could have been seen by the casual observer, whose distracted glance would normally pass-over the surfaces of the world and retain virtually nothing of it. For instance, Eggleston’s photograph of bags of ice in a frosted-over freezer (the sort one finds at a gas station or convenience store on the outskirts of town) initially reads as a study in the subtle gradations of color and texture in the freezer’s whitish blue-green interior, thickly coated in tiny ice crystals, which form horizontal ridges that run from edge to edge of the vertically-oriented picture. Only when we make-out the red lettering on the clear plastic bags of “party ice,” are we able to orient ourselves with respect to what the photograph is a photograph of: a freezer of ice.

Eggleston’s photographs of the American south, for which he is best known, are highly regarded for the candor with which they document the ordinary barrenness of the rural and suburban southern landscape. But it is a mistake to regard Eggleston’s project as essentially documentary in nature. The artist’s painstaking attention to formal concerns such as color saturation and pictorial composition in the images he captures gives his photographs a particular strikingness that stuns the viewer, compelling him or her to fixate his or her concentrated attention on the photographic image. Eggleston himself has explained his approach to photography as follows: “Essentially what I was doing was applying intelligent painting theory to color photography.” Perhaps we do best to understand Eggleston’s photographic practice in terms of the artist’s visual acuity, his gift for being able first to discern, then to isolate, those exceedingly rare moments when the banal materials of the everyday world are aligned just so to make that perfect, momentary image which transcends its own fleetingness through its coincidental engagement with artistic convention.

William Eggleston: Democratic Camera; Photographs and Video 1961-2008, originating at the Whitney Museum of American Art and recently on view at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., is set to open at The Art Institute of Chicago in February 2010 then will continue on to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in October 2010. An exhibition at the Fondation Cartier in Paris from April – June 2009 presented several of his drawings alongside the photographs that inspired them.