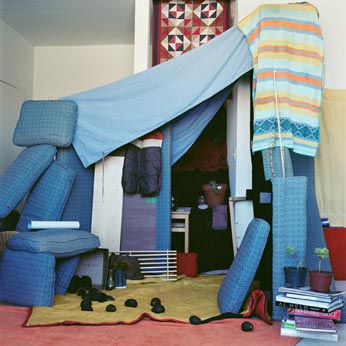

Amir Fallah Dan Cummings (2007) 20″ x 20″ Archival Print

Amir Fallah currently lives and works in Los Angeles. He has exhibited internationally, particularly within the UAE. He is represented by The Third Line and recently showed at the 9th Sharjah Biennial earlier this year.

Reem Fekri: Tell us a bit about your background and your artistic practice.

Amir Fallah: I was born in Tehran in 1979 but since 1987 have lived in the US. I currently live in Los Angeles and have for the last 8 years. I primarily make paintings and sculptures. The subject matters always change but they are always rooted in my personal experiences. Current issues, childhood memories, teenage love, and psychedelic references are some of the most reoccurring themes in the work.

RF: One of the first things I noticed about your work is the constant repetitive use of cacti. In paintings, installations and illustrations, cacti are always present. Can you explain this?

AF: I first began to use plants and cacti as a stand-in for people. Over time they have meant different things in different works. Sometimes they are used as compositional elements, sometimes as way to put some life into the work without having a figure.

RF: I love the forts and sheds that you build – the shed structure that you built at Art Dubai (2008) was a wonderful mess and a mixture of everyday objects. It was an enclosed, transparent ‘shack’ with florescent light bulbs, cacti and various other plants – and most of all I remember the vibrant pink paint that was used in its exterior. Could you take me through the conceptual and physical process of this?

AF: I wanted to create a piece that was rough and violent on the outside but warm and welcoming on the inside. The outside of the fort was paint in camo and the inside was created by a vibrant pink patterned wood. The piece radiated light from the inside, inviting viewers close to it. It could be seen as a metaphor for how outsiders view the Middle East. For those who haven’t been there, it’s seen as this violent, stone-age place but really it’s one of the most beautiful and welcoming areas of the world.

RF: The surrealistic elements in your work become very entertaining to the viewer; how do you want your work to be viewed?

AF: I want all my work to be complex. Too much art is one-dimensional these days. I want the viewer to work hard to unlock the meaning within each piece. What fun is it to look at a painting or sculpture for 5 seconds and digest all of its content? This is too easy. I prefer that the work reveals itself over time so that the more you look the more you discover.

RF: What is the process behind your chaotic compositions that are so vibrant and witty?

AF: I work intuitively on all my work so the process is very spontaneous. I start with a loose image in my head. Sometimes I might do a quick sketch but I start with the idea and resolve it within the painting or sculpting process. This process doesn’t work for everyone but I find that it keeps me engaged with the work.

RF: You have a wide range of experiences that influence your work, such as teenage heartbreak and angst, as well as conversations with your mother. Could you take me through a couple of works that best describes this?

AF: For my last show at The Third Line I painted a piece called The Saddest, Saddest, Saddest Love Song Ever, which depicts Morrissey, Elliott Smith, Johnny Cash, and Robert Smith all hanging out and singing to one another in a fort. I discovered all of these musicians in my teenage years and would repeatedly listen to their various sad love songs. I am simultaneously making fun of teenage notions of romance, while celebrating that feeling that you had when your girlfriend broke up with you and you cried yourself to sleep with Morrissey crooning in the background.

Another key painting in the show was The Ultimate Mom Painting. It’s a very large, exuberant painting of a vase with thousands of flowers in it. It’s about my mothers desire for me to make “pretty” paintings and my resistance. It’s celebrating my mother while at the same time questioning her ideas of how my life should be lead.

RF: Your Fort series is fantastic, particularly Dan Cummings. Each photograph entails the owner (presumably?) of the house building a fort in his or her own living room, using objects found within the house itself. Each one is so different, almost as if the occupier’s identity seeps into the fort. How did this project come about? Were the people chosen randomly?

AF: So far there are six photos in this series. I would go over to a (male) friends house and together we’d construct a fort in their living room or bedroom. We used everyday items such as couches, pillows, quilts, and houseplants to create the structures. Once finished a photo was taken and everything was put back in its place. It was a fun project to see if we could channel that natural childlike sensibility of creating something without an idea of the outcome. The sad part was that as spontaneous as we tried to be the structures always ended up looking like refined sculptures. I guess you can’t escape your age.

RF: Why did you use only men?

AF: The reason I only use men for the photos is because I associated making forts as an activity that I did with my male friends as a kid. There would be times where I would build a fort with a male friend and later on I would go and play with girls inside but I always associated the action with men. I’ve had many female friends tell me that they’ve built forts as kids but my goal was to channel my personal story rather than a universal truth. In the future I am going to do another photo series where I collaborate exclusively with girls.

RF: Are there any references to Persian identity in your work? Do you feel distant to that relation because of your up bringing?

AF: I think there are lots of references to my Iranian heritage within the work. However, I never use that as a crutch or gimmick to gain attention for the work. Right now Middle Eastern art is in vogue. If you look closely you’ll see them in almost everything I make. There are lots of works covered in calligraphy and chadors these days. I find it a bit insulting when people can only identify with 2-3 cultural signifiers. We are more complex than just calligraphy, chador, and miniature paintings.

RF: As an artist of Iranian descent, what do you think of the spotlight attention on work coming from Iran? Is it fuelled by exoticism? Do you feel the work itself is clichéd or overdue for international attention? How does your own practice fit into that?

AF: I think you have to judge the works coming out of Iran on a case-by-case basis.

Some artists are taking advantage of the exoticism associated with the Middle East. However there are others out there that are pushing the limits of what it means to be a Middle Eastern artist. It’s definitely an exciting time for the region.

RF: And finally, tell me about Beautiful/Decay…

AF: I started Beautiful/Decay as a publishing project in 1996 when I was in high school. Since then it has expanded into a brand that collaborates with artists and designers from around the world.

Our flagship project is a limited edition, hand numbered, 164 page book that we release 3 times a year. We also have a popular website where we feature creative content daily. In 2006 we expanded the company to include a clothing line that invites artists from around the world to design limited edition apparel. You can find out more about all our projects at www.beautifuldecay.com

* Amir Fallah kindly donated a piece to START for the Bonhams Auction, which took place in Dubai in October