Taking place at the Somerset House between the 7th and the 19th of March is the ‘Blooming on Paper’ exhibition. I was invited to the private view where artists Annie Edwards and Victoria Kosasie collaborated in a performance titled ‘Paper Score’. Through this collaboration, Kosasie, an award-winning Indonesian artist, foregrounds a few of my humble musings about somatic/performance practices.

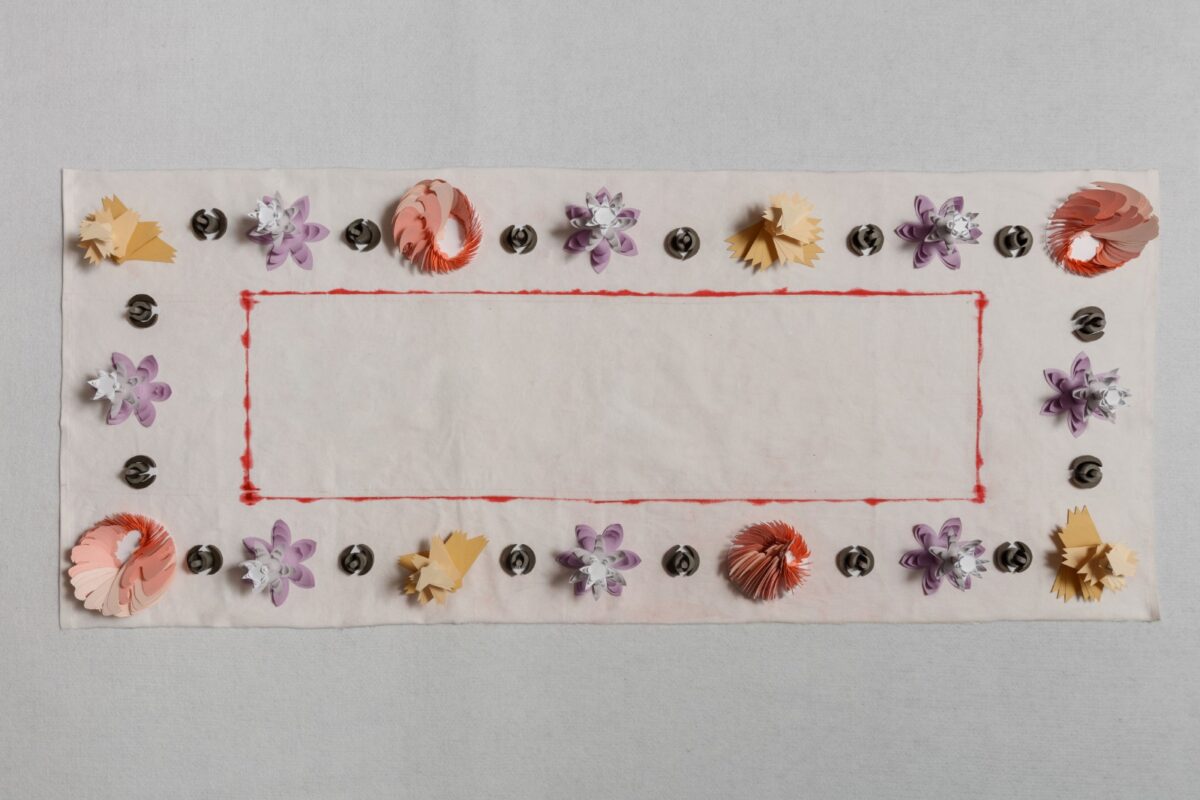

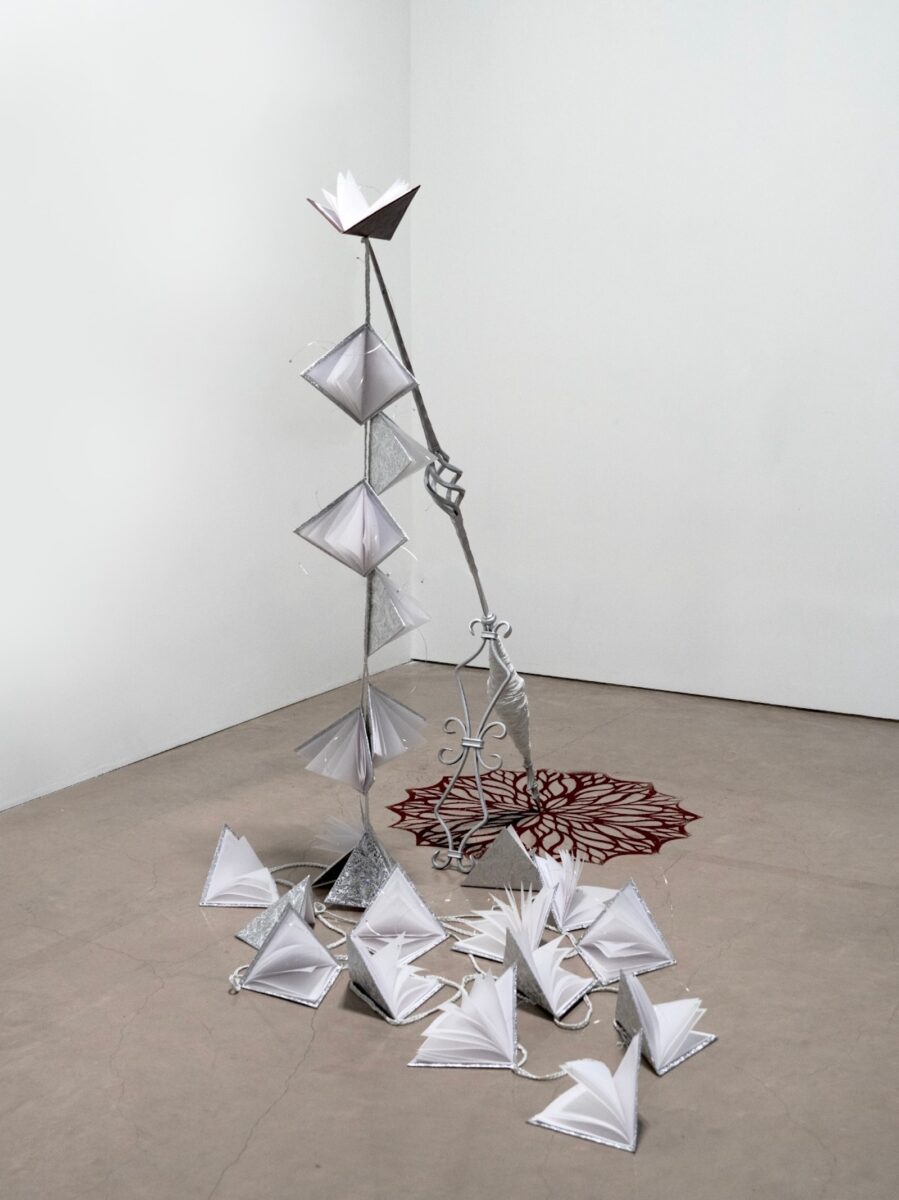

‘Blooming on Paper’ uses the simplicity of paper as a medium for mark-making to consider broader and complex ideas about documentation, memory, rituals, and rebirths. Artist Nayeon Han’s ‘Release to Embrace’ is an installation composed of various coloured papers, foams, and cotton fabrics, all neatly arranged around a blank, rectangular sheet of paper. For Han, the cut and sculpted paper models surrounding the incomplete red rectangle represent the protection of a certain memory and desire for happiness. Sitting in the same space is artist Aura Sun’s sculpture, ‘Once A Lucid Dream’, different pieces of metal supporting one another, suspending in the air gentle folds of tracing paper and strands of delicate silver wire and cotton threads. Sun’s sculpture is successful in evoking a precarity to the space, exploring what is perhaps a fragile liminal space between spiritual and material worlds, between the human spirit and the unending despair of oppressive forces bound to our reality.

The exhibition pays homage to China’s rich heritage of folk art, specifically the art of ‘paper cutting’, a practice for which Xunyi County (part of the Shaanxi province) is recognised. Ku Shulan was born and raised in the Xunyi county as known as one of the country’s most important representatives in the art of paper cutting. As a craft, paper cutting dates back more than a thousand years and is deeply rooted in Chinese culture. With traces beginning from the Han Dynasty’s mythic origins, paper cutting is a ritualistic practice that is tied to the spiritual world, of renewal, of life and death. Ku Shulan’s work exemplified this connection between the personal and the sacred. Recurring across the artist’s oeuvre are depictions of female celestial beings, often manifested through her visions of a deity adorned in colourful flowers. Over time, her dedication to this relationship of mind, body, and soul, transcended her practice from something one might consider as craft at first glance, to an entire cultural heritage that is spiritual, as well as a history that is highly emotive.

I managed to arrive at Somerset House after work, just in time to catch the opening speeches. Shortly after, audiences were led to another room where Edwards and Kosasie stood in opposite corners, each adorning their own stagens, a long and narrow cloth wrapped around their waist which Indonesians traditionally wear to hold in place their kebaya dresses.

Chatter from the audience was promptly hushed when Edwards and Kosasie began approaching the paper screens, indicating the beginning of the performance. I’m always intrigued by how performances begin and end, and when artists/performers become a part of and sever themselves from their performance/work. The pair came to a halt, each confronting their own paper screens that stood adjacent to each around, around 6 feet tall. Synchronised in their movements, Edwards and Kosasie each drew from the back of their stagens a cutting knife.

With their knives unsheathed, the artists began carving from the top of the ivory-coloured sheets, down and around their heads and eventually their shoulders. As the blades tore their way through the fibres of the paper sheets, the two held onto a contemplative expression. The audience, on the other hand, wore a meek concern and other expressions of quiet unease, nervous with each delicate sheet of paper that was cut and cascaded its way down to the ground. With every slice grew an unsettling tension, various trimmings folding over one another, not yet privileged to a severance. The artists, with their bare shoulders exposed, seemed unaware of the possibility of paper cuts that crept closer, as with every cut came along a sharper edge. The fear of a hidden sting that will never quite be enough to make you scream, lingered in the silent atmosphere. I wonder if that came through the photographs I took. They have yet to be developed at the time of writing this.

When Edwards and Kosasie completed the process of cutting their respective paper screens, they stood face to face with a silhouette of their bodies. In addition to the silhouettes are multiple offset cuts, in which both positive and negative space worked together to mimic the diagrams used to chart one’s spiritual energy/chakra (I’m reluctant to use the word ‘aura’). This silhouette is another visual motif that is inspired by Ku Shulan’s practice, specifically the central figure in her work titled ‘The Goddess of Papercut’. Protected under a house and guarded by the light of two lotus lamps, a deity wears a phoenix crown and a ceremonious cape, holding a pair of silver scissors and is seen sprinkling beauty onto the earth. ‘The Goddess of Papercut’ can be considered Ku Shulan’s most celebrated work. In an interview about the work, she says while laughing, ‘I am the paper-cutting goddess. You see that I am audacious!’ With a height of over 150 inches and a width of over 65 inches, the work is a meticulous assemblage of Peircean semiotics framing the feminine as a spiritual sanctum that is noble, grandiose, and majestic. She is the paper-cutting goddess. Her self-esteem is apt to the spirit which flows through this exhibition, not only in recognition of what Ku Shulan means to folk art and female artists but also to celebrate the youthful artistic talent that is on display at the Somerset House.

Paper cutting is a popular practice throughout China, often being used for decorating houses and also as part of celebrations. As a Malaysian of Chinese descent, I grew up with similar experiences, with paper cutting and folding more closely emphasised with rituals and traditions. Paper becomes a really important material as it’s dynamic and capable of receiving various meanings, able to represent different symbols and intentions, i.e., garner prosperity, form prophecies, make spiritual premonitions, protect and renew.

A brief pause was taken by the two artists after they were done with their cutting knives. They retracted their knives and tucked them inside the back of their stagens. Edwards and Kosasie shortly resumed their performance, this time closing down the gap with their paper counterparts. A small cutout was now revealed to the audience, located just above the upper abdomen – the solar plexus. A small but interesting observation is that when the artists tucked their knives away, the audience drew a sigh of relief. Understandably so, as there is often the underlying fear that a performance could go wrong and somebody gets hurt. At the same time, performance art has a history of violence and self-inflicted injury as a means of expression and so pre-empts audiences with caution. When Philippa Snow wrote about Marina Abramovic (who also inspired the generation of Indonesian performance artists before Kosasie), she described how it takes a ‘cool’ and ‘highbrow detachment’ that is youthful and restless in practitioners like Abramovic who would go through with feats of bravery, i.e., relinquishing agency of one’s own body to the public, to hold oneself next to being godlike, akin to a deity. Perhaps it’s this youthful vigour, of not quite being able to predict the narrative of a performance that keeps audiences on their toes.

Edwards and Kosasie made their way around the paper screens and walked through their respective, freshly carved paper silhouettes as if they were portals. During this particular moment, already possessing similar motifs of the deity present in Ku Shulan’s work, the silhouettes came to be a liminal space. For the artists, something that is part of reality yet mystical in quality. When in conversation about ‘Paper Score’, Kosasie highlights ideas about birth and rebirth that are at play during various parts of the performance. One can begin with what Edwards and Kosasie are wearing – stagens are worn by postpartum women in Indonesia. It is worn after a woman has given birth to help their core regain strength. Dancers are also seen wearing stagens to help control their movements in a specific manner. As mentioned before, the hole that was cut and breathed into was located at the solar plexus part of the body. In yogic practices (somatic), the solar plexus is considered to be the third chakra in the chakra system and is associated with empowerment and self-esteem. With Edwards and Kosasie’s performance, considering also the body and the regulation of air and energy (chakra) in yogic practices, ideas about liminality arise. I’m reminded of Dan Fox’s writing about the state of being in limbo and its relationship to space and belonging. Where many might associate the concept with a type of ‘home’, to be able to ‘fit in’ on a spatial level, as well as be amongst ‘neighbours who will include rather than exclude us’, for artists such as Kosasie, being able to exist, perform, and exhibit in spaces such as Somerset House, like her predecessors who mentored her, she is preserving and evolving the legacy and visibility of Indonesian performance art, regarded by her mentors as the few capable of carrying this torch, a bridge between generations of practices.

Paper as a medium is important to Chinese culture but it’s also made relevant within the context of this exhibition. The themes that emerge from Edwards and Kosasie’s performance with paper, i.e., birth, rebirth, and renewal, are consistent with other practitioners who take an interest in the material. In Melanie Miller’s (a senior lecturer in the Department of Design at Manchester Metropolitan University) research on artist and professor Lu Shengzhong’s paper-cutting practice, both the positive and negative forms created when the paper is cut are ontologically essential to the craft. A balance is found where one cannot exist without the other. When Lu is preparing for his exhibition of paper cuttings at the China Art Gallery, the remnants of paper trimmings are just as important to the artist, capable of expressing the same spirit and emotion as what audiences see as the final outcome.

I feel it’s well understood that performance art (that which is somatic) is inherently political. So, when I look at Edwards and Kosasie’s ‘Paper Score’ in relation to the variety of works on display at the ‘Blooming on Paper’ exhibition, the formation of new networks across the Sinophone diaspora through the celebration of female artists on International Women’s Day, brings to mind Judith Butler’s ideas about movements and assemblages; that the politics of alliance not only includes considering the ethics of cohabitation but…

‘what it means to move through public space in a way that contests the distinction between public and private, we see some ways that bodies in their plurality lay claim to the public, find and produce the public through seizing and reconfiguring the matter of material environments; at the same time, those material environments are part of the action, and they themselves act when they become the support for action.

‘Blooming on Paper’ is curated by Yanyi Chen, Tenzi Li, and Yi Zhou, and is supported by King’s College London, the Royal College of Art, NANHU Art Museum, Artscene International Art Incubation Platform, the Shaanxi Artists Association, the UK Beijing Arts Centre, and the Homeward Express.

The exhibition is being held at the East Wing of Somerset House (WC2R 2LC) and is set to continue until the 19th of March 2025. Tickets