There was a flurry of major London exhibitions in the first half of this year that embraced aspects of previously overlooked art histories and I started writing my reviews. Those of Entangled Pasts at the Royal Academy and the Barbican’s Unravel started collecting dust in my drafts folder as I rushed from the Dulwich Picture to the National Portrait galleries for their respective surveys of landscape and portraiture painting by Black artists. And then I got stuck. Something just didn’t sit quite right and I couldn’t put my finger on it.

Several artist talks, panel discussions and a trip to the Caribbean later, it’s time to rewind and review, and to pick up where I lost my thread. I caught a hint of something as yet intangible in a conversation between Max Mara Art Prize winner Dominique White and writer and curator Taylor Le Melle in July. References to the artist’s reluctance to be presented as ‘spectacle’ and the latter’s definition of their curatorial role as that of caring for and protecting the artist – as opposed to preserving a collection of objects – left a lasting mark as they question the role of museums in a changing cultural landscape.

That artist talk was a bit odd compared to similar events; it felt as if the ‘real’ conversation may have taken place elsewhere, away from the audience, the above quoted snippets hinting at something much deeper. Not least at the dilemma of an artist reconciling her museum exhibition with being critical of the historical implications of museum collections. According to the press release ‘her work envisions an Afro future, located outside of traditional utopian science fiction, in an oceanic realm with the potential to offer fluid, rebellious realities, liberated from capitalist and colonial influence.’, yet the exhibition is bound by the institutional and commercial restrictions that come with a sponsored commission.

Deadweight was on view at the Whitechapel Gallery until 15th September with the exhibition catalogue released much later. Announced on the artist’s Instagram as going ‘against the traditions of previous MM winners (in more ways than one)’. I will have to get a copy as I missed out on another chance to spend time with the installation, wishing away the health and safety measures of taped borders and bright emergency exit signs that prevent visitors from fully immersing themselves in the daunting and fragile underwater world represented by these ominous works.

References to boats and water, in particular the Middle Passage and the loss of life during the forced voyage across the Atlantic, amount to a poignant theme with artists presenting the human aspects of histories that are often reduced to numbers. The mythical underwater worlds presented by Wangechi Mutu and Ellen Gallagher as part of last year’s In the Black Fantastic, and more recently John Akromfrah’s Vertigo Sea as part of Entangled Pasts have left lasting impressions. I can’t remember where I first encountered Lubaina Himid’s series of Le Rodeur paintings whose characters present elements of a story you never forget once you’ve read the wall text.

If it wasn’t for an artistic intervention, I wouldn’t have been aware of a refurbishment programme at the National Maritime Museum. The museum’s Atlantic Worlds gallery recently reopened with a redesigned display that centres on the previously untold human stories linked to the objects. Contemporary artists Elgin Cleckley, Joseph Ijoyemi and Karen McLean were commissioned to respond to historical artefacts. The artist’s interventions and revised texts aim to put the expansion of British trade and Empire into context of African and indigenous societies, before during and after the period of transatlantic slavery, as well as counteracting depictions of violence and trauma with stories of resistance and joy. The opening event included a performance by Othello De’Souza-Hartley that compared human resilience and adaptability to the infinite flow of water in its many guises; a small drop in the ocean swelling into a powerful ravine, circumventing obstacles while carrying heavy loads.

This was the first example of a London museum addressing its colonial past by reassessing and adapting its permanent collection that I became aware of. I experienced another example at the Barbados Museum in Bridgetown, where most of the wall texts had been updated, placing historical artefacts into postcolonial context, while overall the island’s main museum still resembled the type of old-fashioned institution you only enter when it rains on holiday. Visitors are greeted by one of Gloria Daniel’s black plaques which I recognised from her London exhibition last year when the artist launched a campaign for ‘institutions who have historically honoured individuals who profited from the transportation and enslavement of African people to accurately contextualise their history’.

Here, too, it was the contributions by contemporary artists that highlighted the human experience of complex histories. I was lucky to catch a temporary exhibition that was originally scheduled for a six-month run in 2023 and had been extended into summer 2024. LOOKA: Dismantling the Colonial Gaze comprised responses by five local women artists to the museum’s collection of historic postcards. Working predominantly in photography, Risée Chaderton-Charles, Jalisa Marshall, Joy Maynard, Amber Newton and Kia Redman challenged the exploitation of Black bodies, in particular the lost identities of the island’s unnamed makers and vendors. To counteract the depiction of people as commodities alongside the goods they make or sell, the artists celebrate the life stories of contemporary Barbadians and their links to the island’s heritage.

All emphasise the importance of the subject’s agency in photography, whether by naming their subjects or by deliberately keeping faces hidden from view to avoid objectifying individuals. Writing postcards may have gone out of fashion and those of sunsets and beaches still available across the island haven’t changed for decades, yet few tourists ask for permission before snapping away at the beach or fish market, inadvertently still applying a colonial gaze.

Catalogues and reviews are all that remains of most exhibitions. The majority of the major London institutions has since returned to crowd pleasing programming, with the Royal showing Michael Craig-Martin and Francis Bacon headlining at the National Portrait Gallery, while Van Gogh and Monet are celebrated at the National and Courtauld Galleries respectively.

And then Hew Locke stages an intervention at the British Museum and shows them all how it’s done with a curation based on a thorough deep dive into the archives. What have we here? is confined to a relatively small room and unfortunately won’t be permanent either but is the strongest example of how to reposition historic collections in visitors’ minds, if not in the museum itself.

While not as closely linked with its permanent collection as the RA’s Entangled Pasts, The Time is Always Now which opened at the National Portrait Gallery in February provided a comprehensive introduction to contemporary Black portraiture, many in direct reference to the displays on the institution’s upper floors.

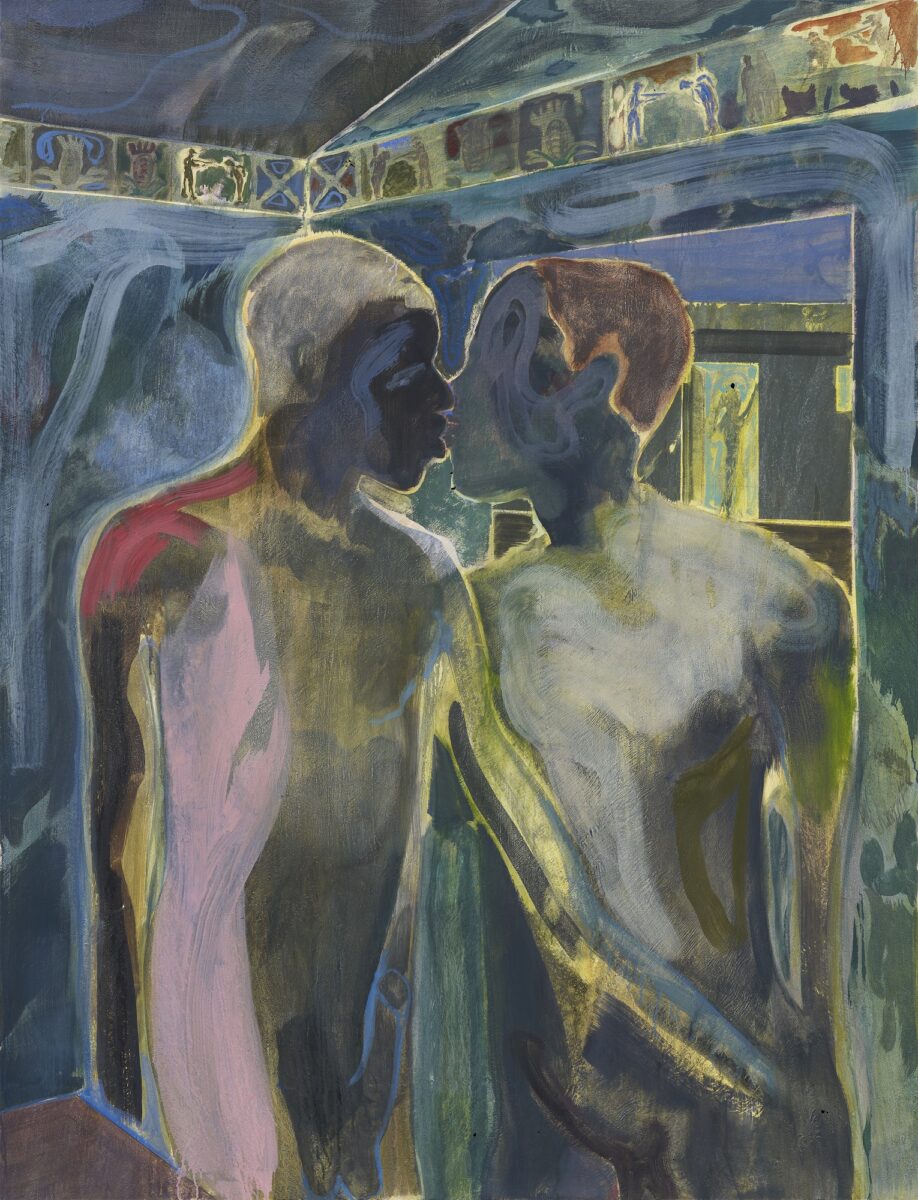

Presented across three themed sections, the exhibition opened with Thomas J Price’s monumental bronze displayed against a sombre backdrop, a formal reference to the colour schemes of the traditional displays where non-white figures are largely absent or at best anonymous. The opening section’s title ‘Double Consciousness’ describes the experience of ‘looking at one’s self through the eyes of others’, the works on display interrogating the white gaze from a multitude of angles.

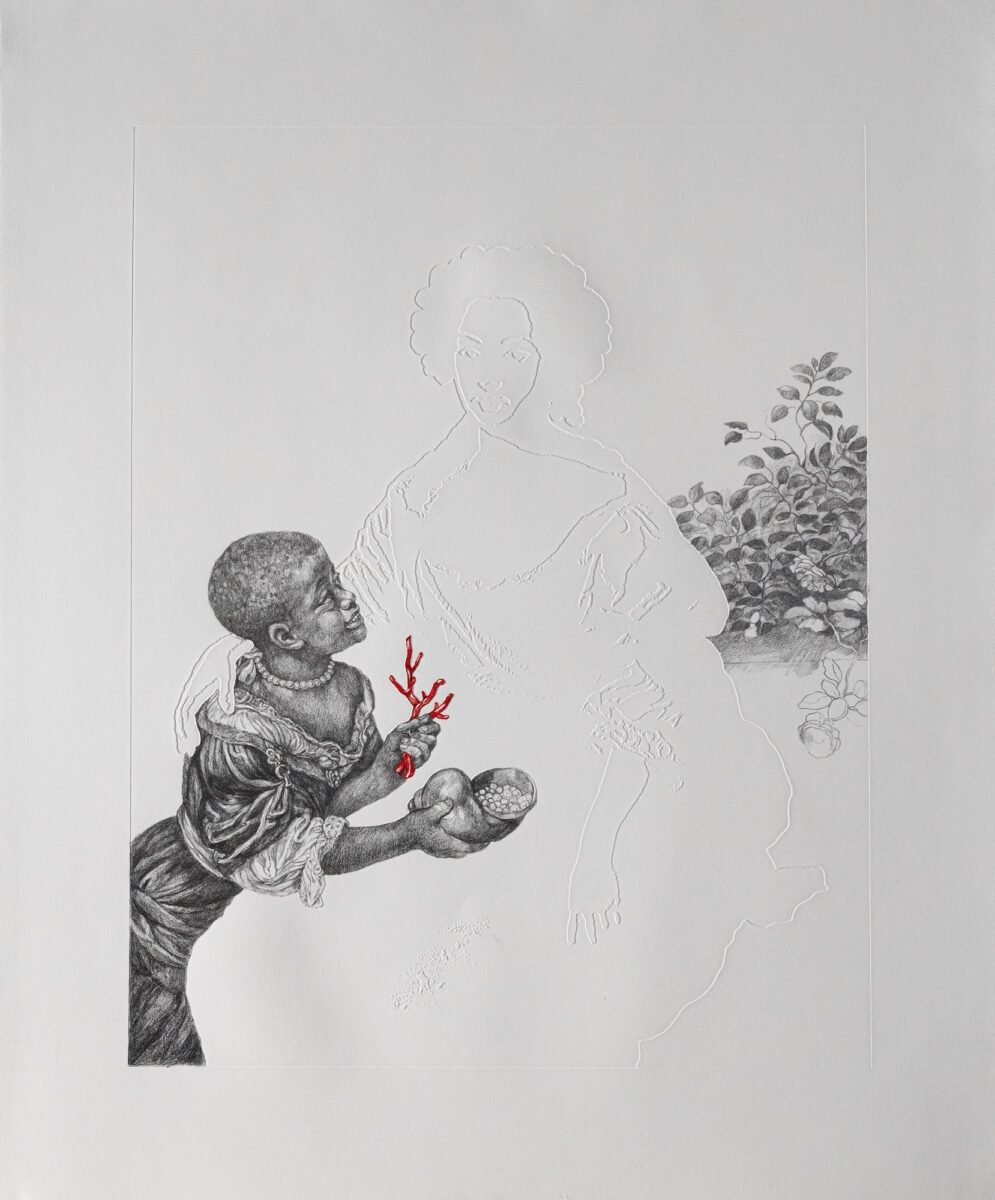

Curated by Ekow Eshun who previously presented a visual feast based on non-white narratives with In The Black Fantastic at the Hayward Gallery, The Time is Always Now comments on the lack of Black characters in the master discipline of Western art historical hierarchies. This is illustrated most poignantly in Barbara Walker’s series of Vanishing Point drawings that give visibility to overlooked Black figures depicted in Old Master paintings, including some held in the National Portrait Gallery’s collection. Part of the ‘Past and Presence’ section, the walls in this room are painted a similar red to those of a permanent display that includes Sir Joshua Reynolds portrait of Mai (Omai), dated about 1753-80, described as ‘the first British painting to depict a person of colour with dignity and grandeur’.

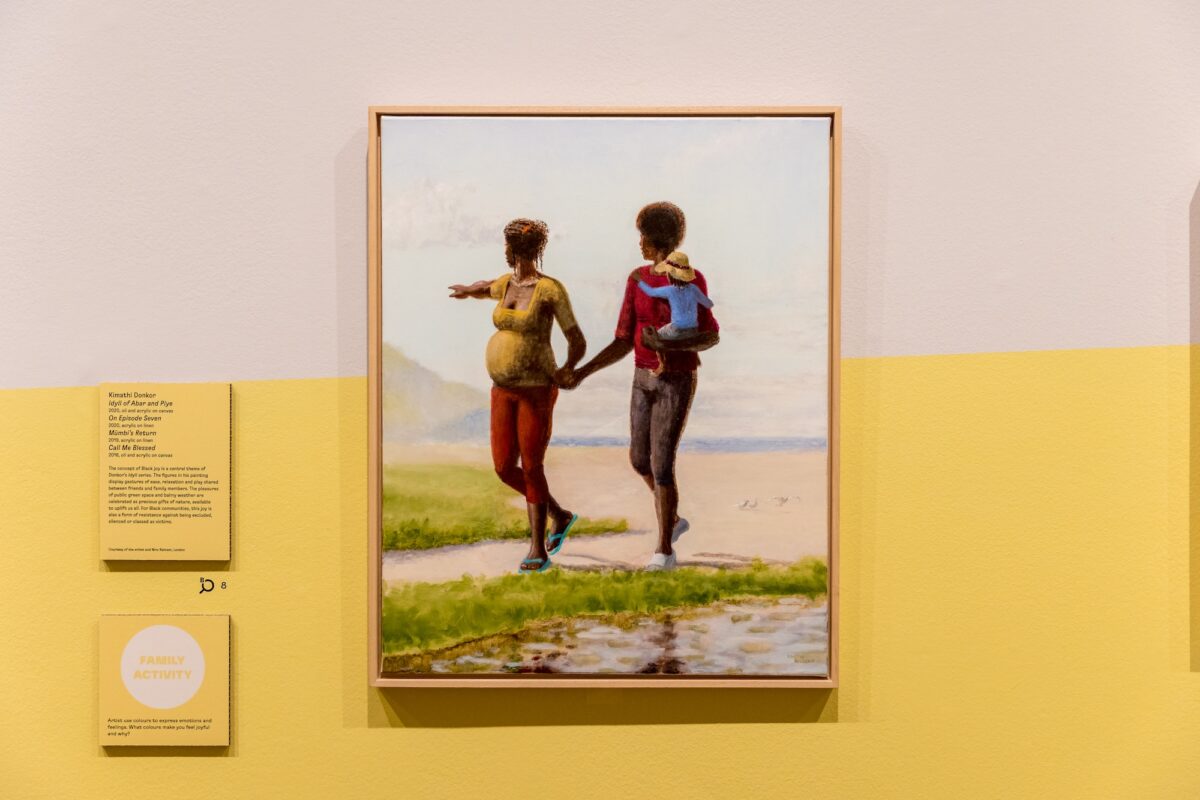

The final section entitled ‘Our Aliveness’ is presented as a place of relaxation and recreation, a stylised playground with a textured green floor and relaxed benches surrounded by artworks depicting contemporary Black life. The exhibition has since travelled to The Box in Plymouth and on to the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the US (maybe the reason for the large proportion of American artists included in the show) and I wonder how the displays were translated to suit these spaces.

I wish I had experienced The Time Is Always Now before visiting Soulscapes which opened the week prior at the Dulwich Picture Gallery and was billed as an exhibition offering interpretations of landscape art by contemporary Black artists. The contrast between the gallery’s location and history, and the curator’s intention of making the exhibition accessible to visitors from less privileged neighbourhoods resembled the experience of travelling by the exhibition by public transport and taking a bus from Brixton station for the final stretch. The demographic on board dramatically changed from majority young and Black to middle-aged white women like me.

Dulwich Village evokes a sense of entering an alternative reality, more 50s suburbia than millennial London with its picket fencing and wooden road signs. The surrounding parks and lawns resemble the pastoral idealisation depicted on the European masterpieces in the Dulwich collection. Landscape painting became popular during the seventeenth century and plays an important part in Western art history. The genre’s links to empire building and colonialism are less well documented, nor is there an obvious link between Soulscapes and the gallery’s permanent collection.

As if leading on from the final room of The Time Is Always Now, Lisa Anderson took a joyful approach to curating landscapes by artists from the African diaspora. This was not the only parallel between the exhibitions which both used well-established genres to view the world from a non-European perspective by inserting Black figures and experiences where they are missing from art history. Several of the artists were included in both exhibitions with Hurvin Anderson, Kimathi Donkor, Michael Armitage and Njideka Akunyili Crosby blurring the lines of a classification that generally separates people from their environment. Soulscapes closes on a large-scale commission by Micheala Yearwood-Dan whose abstract collage merges painting with ceramic and word elements.

But whereas the playful layout of the National Portrait Gallery enhanced the exhibition’s overall narrative, the exhibition design at the Dulwich Picture Gallery did not seem to work and stopped me in my tracks. The pastel colours meandering through the narrow stretch adjacent to the permanent collection’s grand halls made the rooms resemble a children’s nursery, distracting from rather than channelling the sun-bleached atmosphere captured in the paintings and photographs. I loved the art, but it took a return visit to Dulwich and a holiday in Barbados to understand what made this the right exhibition in the wrong place. It can be hard work to acknowledge one’s own white gaze and hegemonic conditioning!

Fingers crossed for more challenges and opportunities to broaden art education in 2025.