Entering the Barbican art gallery, you’re immediately immersed in a world of noise and sounds, humming, laughter, chatting of children engaged in various playful activities. Towering video screens tempt your eye, but before you move inside the gallery space, a painting, modest in size by comparison, sits at the gateway. On a background of shiny goldleaf, cut-out eyes of different colours look straight at you – the viewer. Inspired by a 2016 photograph of Yazidi children taken by Francis Alÿs in a Sharya refugee camp (Northern Iraq), these eyes take on a multitude of meanings. They range from wondering what horrors the children must have witnessed, to a sense of awe for their incredible resilience. There is, however, a deliberate gesture in positioning this work right at the start, and the message is clear: these children’s eyes are upon us. They hold us accountable.

Francis Alÿs: Ricochets is a major new retrospective (Barbican Art Gallery, until 1st September) by the Belgian-born, Mexico-based artist, 14 years after his previous UK show at Tate. Major museums and galleries have exhibited his work around the world in the meantime, and he represented Belgium at the 2022 Venice Biennale.

The Barbican exhibition surveys Alÿs’s renowned Children’s Games, a celebrated series of films recorded by the artist across many different communities and contexts – from hyper-dense urban metropolis to rural sites, remote villages, and refugee camps, all around the world, depicting children as they play out in the streets and in the open.

A new body of work is also on display in the upper gallery.

Originally trained as an architect and urbanist, Alÿs is one of those rare artists whose work is immediate, accessible, profound, on a human scale, and absolutely brilliant.

Over a career spanning more than 40 years, Francis Alÿs has developed a distinctive and groundbreaking practice that includes painting, drawing, film, and animation. The rapidly changing urban landscape and the resulting shifts in social dynamics during the late 1980s inspired him to become a visual artist, leading to his early public interventions. Notable works such as Paradox of Praxis I (Sometimes Making Something Leads to Nothing), 1997, where Alÿs pushed a large block of melting ice through the streets of Mexico City for nine hours, quickly cemented his reputation as a leading artist of his generation. Collaborating with local communities worldwide, Alÿs engages with cross-cultural contexts from Latin America to North Africa and the Middle East, moving beyond dominant Western-centric narratives.

What emerges is a lifelong exploration of art as a vehicle for witnessing social and political change. With much of the current conversation on urbanism rotating around the playful city, his Children’s Games collection – which began in 1999, 25 years ago, feels entirely pioneering.

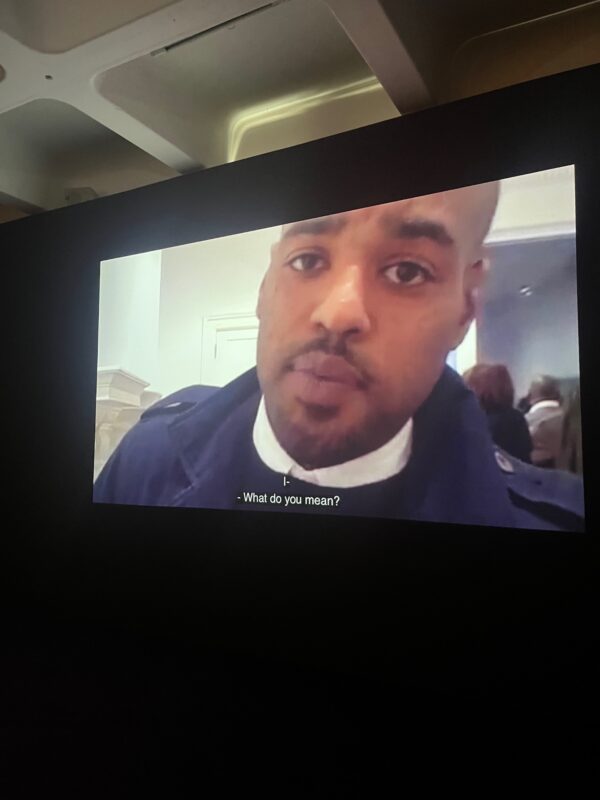

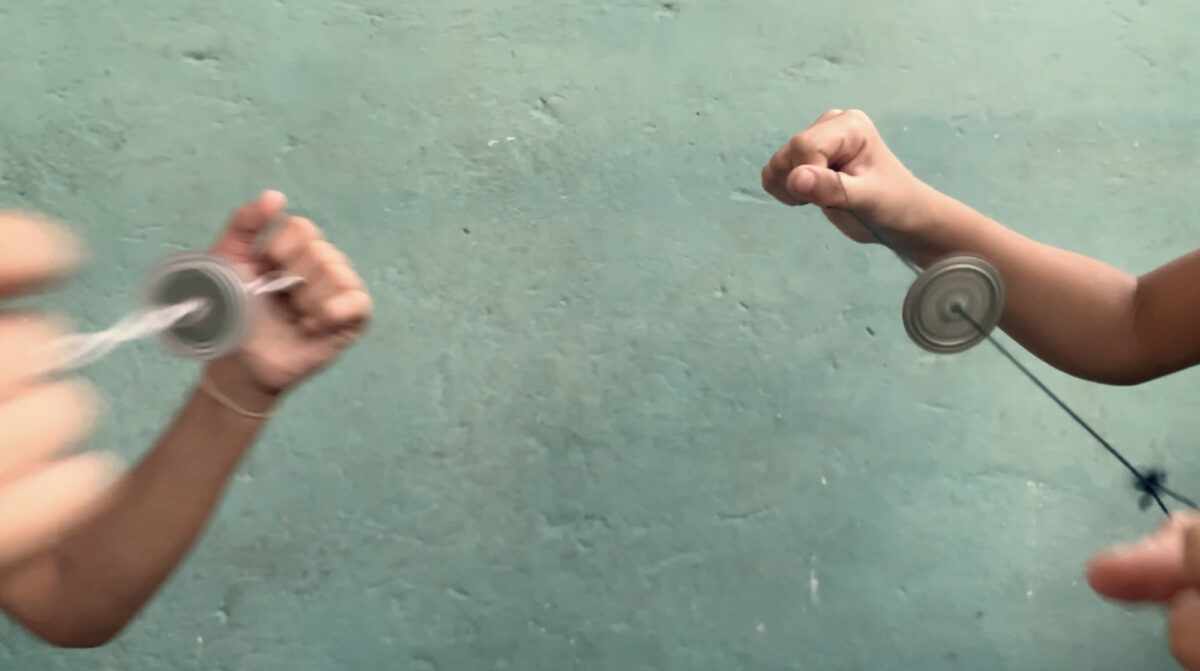

There are over 30 films on display across the ground floor. In Chivichanas, (a makeshift wheeled board built of discarded wood), the camera shares with the viewer the chivichanas races through the streets of Havana, Cuba; children piled on these contraptions fly at high speed down roads full of sharp corners and bumps. The camera shares with us a benevolent gaze, one that is also deeply interested in the game being played. It is not voyeuristic but inclusive – the viewer becomes part of the local community keeping an eye on the children as they race with their wooden carts. As the adults watch on from balconies and pavements, amusingly entertained by the races, we are transported as if standing with them, in a deeply human transition from Havana’s back streets to the Barbican gallery.

In Chapitas, instead, the camera shows a close up and intimate moment of play, pulling us through the midst of a chapita (bottle top) fight. The children’s facial expressions carry us through this moment of play. A bird caged in a red wooden box perhaps is there to remind us that we are, after all, living in a cage too.

Conkers takes us to a council estate in Hackney. Children throw the conkers looking deeply engrossed in the game. There’s a sense of aggressivity in their expressions – they look dead serious, smashing their rival’s conker with skilful precision. Their focus razor sharp.

There are too many stories to tell them all. Most of the games filmed feel familiar, however unfamiliar their context is. To watch them, is a unifying human experience. From stones rebounding on water on a clear evening light; feet spinning around in circle until the child vertiginously collapses; rope skipping on a tiny balcony, a huge estate enveloping three children as they rhythmically keep on skipping; hopscotch played through a muddy and desolate refugee camp, the children, looking cold and dishevelled, playing in an orderly manner, surrounded by barbed wire and make-shift tents. It is hard to watch. As I make my way through the videos, a deep sense of connection, of human belonging, fills my heart. Play is universal and necessary – a tool to rescue humanity in all conditions.

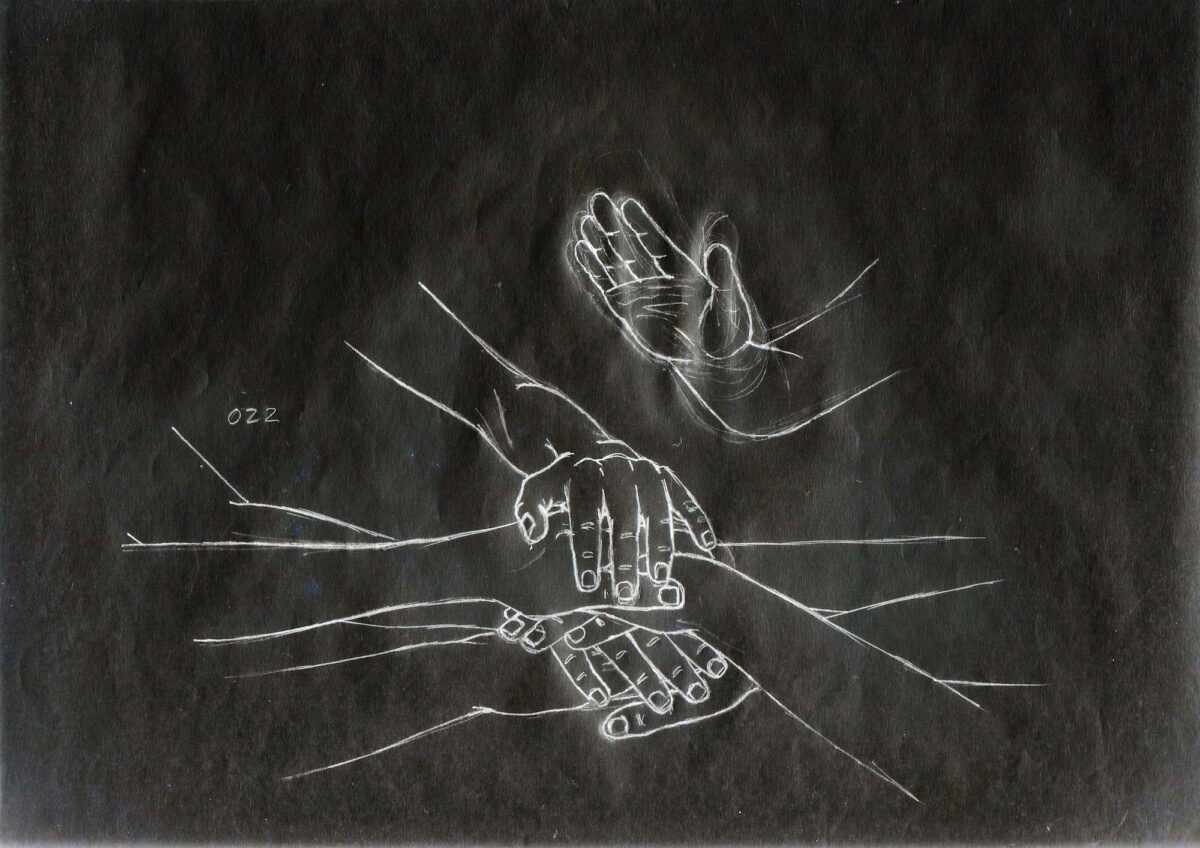

The second section of the show, upstairs, houses a much quieter and meditative new body of work. It charts, through pared back, minimal animations in white line drawings over a black background, the simple rules of hand games – from hand stacks, paper scissors rock, hand shadows, and so on. It is an immersive display of small, considerate gestures.

In a dark gallery, a small painting in the far-end corner lures you in. I tentatively step through the darkness. A perfectly formed small oil painting shows us a child, counting with his head on a tree, ready, perhaps, for a game of Hide and Seek. The darkness mimics the child’s shut eyes while he counts, and I can’t avoid but to wonder whether his friends are hiding somewhere around in the dark room. The thought is slightly disturbing.

Two playrooms complete the exhibitions. Over 60 children from local Barbican schools have been involved in creating a set of instructions for visitors to follow as they engage with the spaces, which are free flow. Of course, the viewer may choose to follow the instructions, or simply make up their own rules as they go along.

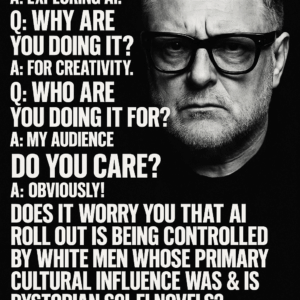

During the press conference, Alÿs notes that throughout his 25 years of researching and documenting Children’s Games, something has changed across all strata of population and geographically across the entire globe.

Alÿs states that

this [body of work] is something that has an urgency, it is disappearing. I am not being judgmental, but simply creating an archive. Children’s interaction with urban space is not coded through play anymore. This project documents children’s play on the street – which is a rare occasion’.

‘It is important to register those games where they are still happening – as they aren’t happening anymore as they used to. […] continues the artist. ‘Games that have been around for 4,000, 5,000 years are quietly disappearing. Even in remote corners of the world, it may be possible to find adults that still play those games, but children seem to have moved on – it’s not something that is happening in large urban environments only’

My initial interpretation – play as a universal tool to rescue humanity – is quickly turned around on its head. The positive sense of hope in children’s resilient playfulness leaves space for a series of worried considerations: another defining trait of humanity is being lost. What can be done about it?

The Children’s Games series is also available, completely free, online. What an incredibly relevant and wonderful tool for collective memory.

Francis Alys, Ricochet, is a the Barbican Art Gallery until 1st September.