Barely recovered from the might of Entangled Pasts, 1768-now at the Royal Academy, a major show tackling the academy’s connection to colonial histories, and on to the Barbican and Unravel: The Power of Politics of Textiles in Art.

While the RA show adheres to the traditional academic hierarchy that considers painting as the highest genre, followed by sculpture, drawing and printmaking as the only other recognised disciplines, the Barbican dedicates an entire show to textile art, a genre that has been marginalised and deemed inferior.

As a younger institution established in the late 20th century rather than at the height of Britain’s Atlantic trade in enslaved African people, the Barbican’s approach allows for more curatorial freedom with the institution’s own heritage not directly linked to Britain’s colonial past. With a selection of artists reaching far beyond Britain and its empire, the stitched, woven and threaded works range from miniature to monumental.

Unravel lets viewers off the hook and allows them to decide whether to read the accompanying wall texts, to just enjoy the experience of materiality, beauty and skill, or whether to defy the recommended order of rooms and start exploring the lower galleries before moving on to the upper displays.

The warm colours of Cecilia Vicuna’s spatial installation are visible from almost every aspect of the gallery and feel like rays of sunshine flooding the concrete environment of the windowless space. As at Magdalena Bakanowicz’s recent solo exhibition at Tate Modern, the organic fragrance surrounding her monumental fibre sculptures adds a sense of primal wellbeing. Another sensual highlight is Igshaan’s Adams’ room on the floor above.

Love, joy, hope and wonder are woven throughout the exhibition. So are stories of oppression and liberation, memories and migration, ecology and extraction; some plain, some hidden; sewn into quilts, woven into tapestries or wrapped in cloth. Unravelled and rethreaded across sections of international, intergenerational and intersectional conversations.

With the oldest works in Unravel dating from the 1960s, notions of empire are not the main or most obvious subject of the exhibition, yet references are woven through the displays. Antonio Jose Guzman and Iva Jankowicz create textile worlds of cultural exchange, their patchworks illustrating the complex history of indigo. Yinka Shonibare’s signature Dutch wax prints embody the link between Indonesian batik and cotton manufacturing in Manchester that led to the designs becoming synonymous with West Africa – colonial trade routes that are particularly poignant as the show will move on to the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam later this year.

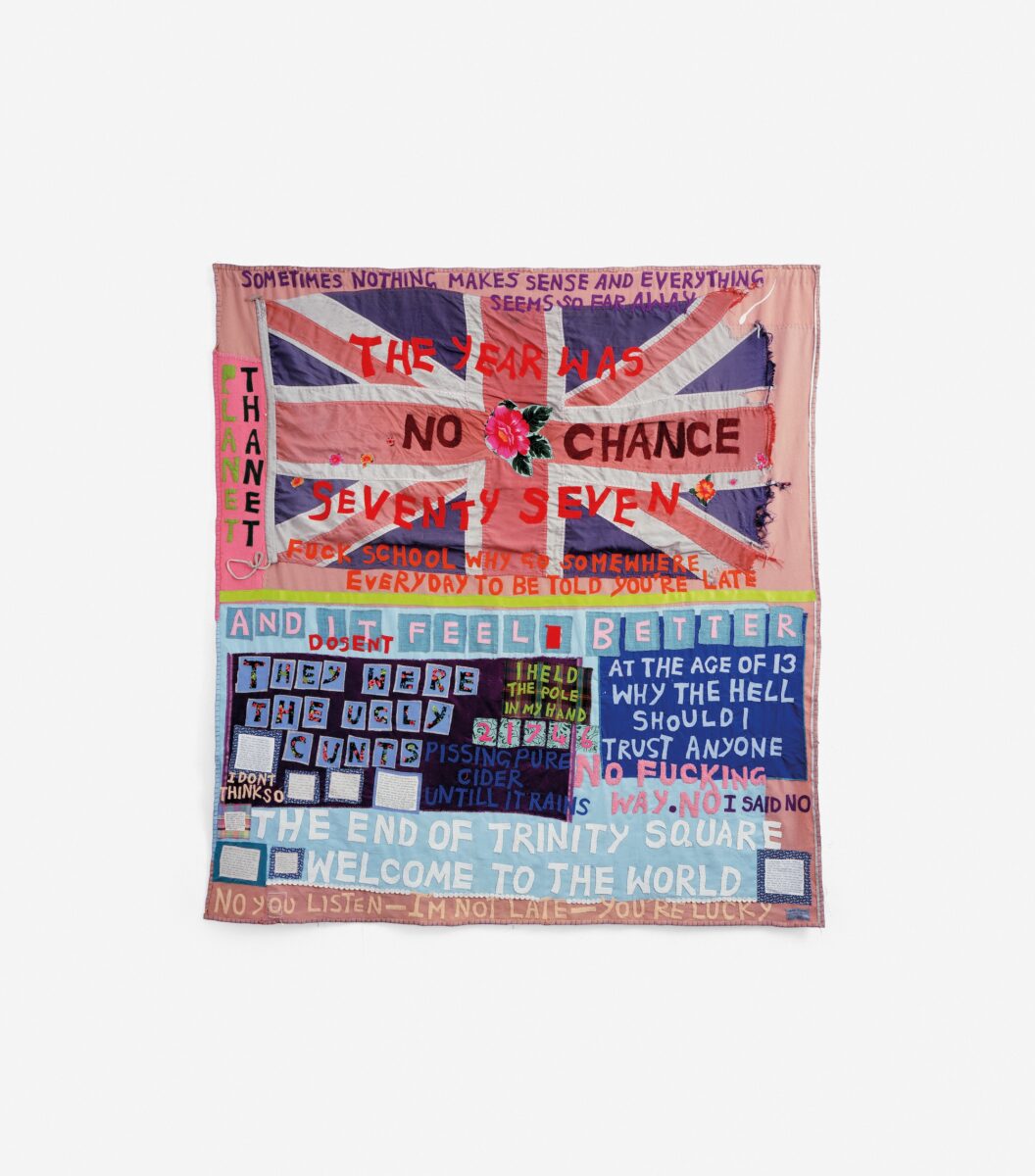

Flags and maps acquire new meaning with hidden routes for enslaved freedom seekers encoded in Sanford Biggers’ quilts, or Cian Dayrit’s embroidered maps of Philippine islands and Myrlande Constant’s Haitian flags commenting on modern capitalism; even Tracey Emin’s Union Jack embroidered in 1999 carries a different weight in post-Brexit Britain.

As with John Akomfrah’s video over at the RA, it’s the aquatic scenes that have had the most visceral effect on me. Tau Lewis’ The Coral Reef Preservation Society pays homage to the enslaved women and children who lost their lives during the Middle Passage. Working with salvaged and repurposed textile the patchwork challenges classist, racist and capitalist biases still prevalent today.

With textiles part of everyone’s everyday life, Unravel never alienates, gently revealing both comforting and uncomfortable truths to those willing to look beyond the surface – the reverse of many works is as powerful as their front view.

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican Art Gallery, until 26th May 2024

Tickets from £18; concessions available; under 14s go free (T&Cs apply);

Pay What You Can visits take place every Thursday from 5PM – 8PM.