Ibrahim Mahama: Purple Hibiscus – #REVIEW- ‘At least 1000 people have worked together in this piece, it took us nearly 6 months,’ says Ibrahim Mahama, standing by the doors of the Barbican’s Lakeside Terrace, having wrapped its façade with over 2000 square meters of traditional Ghanian hand-woven fabric of colossal size, in vibrant pink and purple colours.

Purple Hibiscus, the first large-scale UK public commission by the renowned Tamale-born artist, is named after Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s eponymous novel, and features two kilometres of bright magenta textile material, hand-made by an army of weavers in his hometown, adorned with batakaris robes – 130 of them – embroidered on the colourful panels, spread out ‘like flowers’; their marks, head openings and unique shapes carrying the memories of the people who wore them. Some of the batakaris are sewn inside out, some showing the stamp of one of Ghana’s leading flour producers; the screen-printed company logo is typically found on jute sacks used to store flour; once emptied, these sacks are then widely repurposed to line the traditional batakaris garments, with the jute taking on a new life, sitting in close contact with the skin.

Worn in Northern Ghana by all strata of the population, from Royals to ordinary people, each batakaris’ unique colours and stitching techniques is linked to specific villages and tribes, carrying a geographical and societal imprint within each fibre. Highly ritualised garments, the batakaris are considered an embodiment for the person who wore them.

Sometimes used for decades, the garments end up collecting the shapes of the bodies they clothed; some show signs of sweat and marks of bodily fluids imprinted within the fibres of the jute lining, something the artist has been particularly keen to explore throughout this commission. ‘I’m interested in how the DNA of the people who are connected with these robes is now part of a public commission on the façade of the Barbican; exposed to the elements, their DNA will drip down and melt within the architecture of the site, connecting with the DNA of the hands who hand-carved this façade. It is a shared history of labour that I wanted to reflect on,’ says Mahama.

Mahama also points out how the thread used to weave the giant textiles, onto which the batakaris are sewn on, is originally imported from China, and becomes strongly rooted in Ghanian culture only through the act of weaving, highlighting his concern with the physicality of objects, and how they carry an embodiment of their makers through labour.

The title ‘Purple Hibiscus’ came after Mahama decided that he was going to approach the brutalist façade of the Barbican’s Lakeside terrace by introducing a warmer hue, choosing vibrant pinks and purples to counterpoint the concrete starkness of the building. This is also a departure from the artist’s usually pared down colour palette, where natural tones, deriving from raw materials – clay, jute, earth – aren’t usually modified.

Furthermore,

‘the reference to Adichie’s novel is contextual,’

says the artist.

I am not here to tell a story of violence but once I chose the colours, I then immediately thought that Purple Hibiscus would have been a perfect title for this work, as the novel is set in a context I recognise’.

Works by Christo and Jean Claude, and Alberto Burri are often mentioned in our conversation, with Mahama’s famous ‘wraps’ often being brought to comparison. Christo’s courage to break free from the traditional norm and using form in a completely new way is something that Mahama is fascinated by, but it is Arte Povera, and Burri’s take on everyday materials used as vessels for the stories of the people who made them, and used them, that resonates with Mahama’s own artistic practice.

Mahama was born in Tamale, in North Ghana, a traditional and conservative region; through his work, the artist is very much focusing on sharing knowledge and learning practices from and with the community, in a mutual exchange. The epic scale of the work speaks loudly of a large scale community effort, with the artist collaborating with hundreds of women weavers and sewing collectives – men and women, to produce this commission (whom he was able to pay directly). Famously, his Red Clay Studio (open in 2020) and Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art (open in 2019) in Tamale, as well as the Nkrumah Volini, an institution for archaeological memories, have been providing infrastructure for exhibition making and arts education. This approach is at the core of Mahama’s belief that all Ghanaians – and all Africans – should have access to art, be able to experience it, and, in this case, also able to shape it.

Purple Hibiscus, gently flapping in the wind, is vibrant and joyful even on a day as grey and typically British as today. As for the visitors of the Barbican, who may be encountering his installation by chance, Mahama hopes that they’ll be able to reflect on the labour that has gone into it, returning to one of the core elements in his practice – the importance of using ordinary objects to highlight the human labour behind it. This creates a strong connection with the Barbican itself, and the labourers that built it. Furthermore, by highlighting the form of the building and by hiding it, Mahama hopes that visitors will be able to appreciate its architectural nature through a different lens. Transported to the Barbican, this commission not only encourages a different understanding, where colonialism, and exploitation of labour and of slavery gain new meanings; it is also expressing allyship with marginalised communities, who are taking centre stage in this work.

“I am always interested in the way in which we can connect different spaces, we can connect histories with materials that can be used over and over again, and begin to create a shared community. I am always looking for a thread that brings all the elements together”.

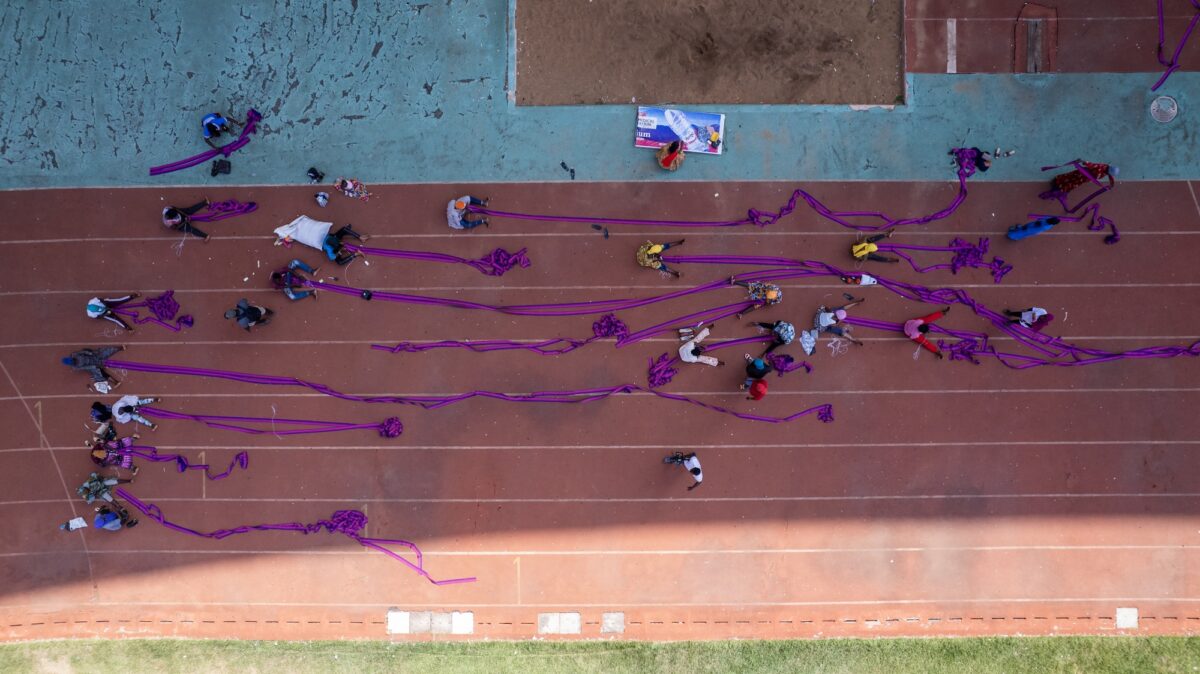

A video charting the making of the work adds beautifully to the understanding and appreciation of the immense scale of the work, showing the communal efforts in sewing together the large textiles, which were assembled in Alui Mahama sports stadium in Tamale, transformed into an open-air artist studio. Arial shots showcase the scale and level of community participation, with the purple shapes captured from a faraway drone transformed in almost abstract forms, taking over the vast majority of the stadium, with hundreds of people working side by side.

Words MBD

The commission is part of the exhibition ‘Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles and Art’ at the Barbican Art Gallery. It will be on display until 18th August 2024.