It’s a travesty that Yoko Ono is too often discussed in the context of her marriage to John Lennon and dismissed as the woman who broke up The Beatles, without reference to her incredible accomplishments as a trailblazing conceptual artist. Ono is one of the most important women artists of the past few decades, a pioneer of conceptual, participatory and performance art in a similarly ground-breaking way to the other Grand Dame of conceptual art – Marina Abramovic.

So the Yoko Ono retrospective Music of the Mind at Tate Modern feels like an overdue retrospective, and a unique chance to experience some of her seminal conceptual and performative artworks, and get an insight into her musical back catalogue, her artistic practice and her ongoing campaign for world peace.

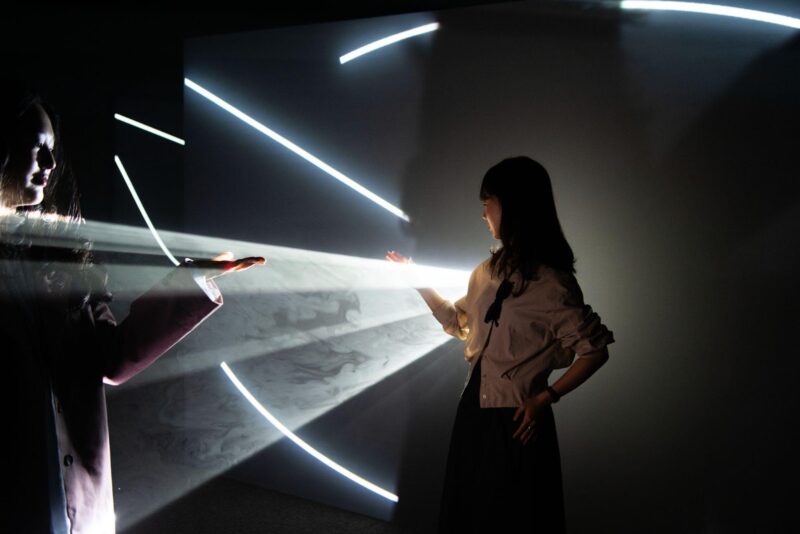

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind covers a period of more than seven decades – from the mid-1950s to the present day – and is the UK’s largest exhibition celebrating key moments of Ono’s influential and multidisciplinary career. The exhibition traces the development of Ono’s practice and explores some of her most talked about and powerful artworks and performances including Cut Piece (1964), where people were invited to cut off her clothing, and her banned Film No.4 (Bottoms) (1966-67) which she created as a ‘petition for peace’. Music of the Mind invites visitors to interact with Ono’s conceptual works such as ‘Wish Trees for London’, where visitors can contribute personal wishes for peace.

Ono was born in Japan and developed her practice in the United States and later in London, where she met her future husband and long-time collaborator John Lennon. More than 200 works are featured, including instruction pieces, scores, installations, films, music and photography that epitomise Ono’s visionary approach to language, art and participation.

The timing of this exhibition seems particularly poignant and emotional – two years since Russia invaded Ukraine, while war rages in Sudan, and the death toll in Gaza passes 30,000. Yoko Ono was a child growing up In Japan during World War II, a deadly conflict that ended with nuclear bombs destroying Hiroshima. She was an adult in the 1970s when she staged a “Bed In” peace protest with John Lennon, as a protest against the US war with Vietnam, asking that we “Give Peace a Chance”. Yet here we are decades later, and humanity seems to be regressing as conflict rages around the world. And as always it’s the innocents whose lives are destroyed, who are displaced or killed, while those in power seem either apathetic or powerless to promote peace and unity.

A particularly striking film shown at the Tate Modern is of Yoko Ono’s 1964 performance piece ‘Cut Piece’ and shows people gradually cutting off her clothes with a pair of scissors, and capturing the discomfort on her face as a man cuts the straps of her bra. ‘Cut Piece’ reminded me of Marina Abramovic’s legendary 1974 Naples performance ‘Rythmn O’, which left her traumatised when male members of the audience terrorised her. There are definitely parallels between Abramovic and Ono, and it’s interesting that both women have been given long overdue retrospectives at major arts institutions within a few months of each other.

However, the Yoko Ono exhibition is generally a more serene and peaceful experience than Abramovic’s recent retrospective at the Royal Academy of Arts. Whilst both women are trailblazers of performance art, the Yoko Ono exhibition feels more like an anti-war protest and a document of her dedication to promoting peace

My favourite room of the exhibition is titled ‘Surrender to Peace’ and brings together Ono’s works from the mid-1960s to 2009, revealing her use of the sky as a metaphor for freedom and limitlessness. Through her artistic practice, Ono has been on a lifelong mission to heal the self and the world with a message of peace.

In 1983 she placed an advert in the New York Times titled ‘Surrender to Peace’, which is sadly just as appropriate now as it was 4 decades ago. She wrote

“Our purpose is not to exert power, but to express our need for unity despite the seemingly unconquerable differences. We as the human race have a history of losing our emotional equilibrium when we discover different thought patterns in others. Many wars have been fought as a result. It’s about time to recognize that it is all right to be wearing different hats, as our heartbeat is always one.”

Concepts of trauma and healing are at the heart of Ono’s artwork. Since her family fled the bombing of Toyko during the Second World War, she found comfort in the sky above, remembering that “Even when everything was falling apart around me, the sky was always there for me…I can never give up on life as long as the sky is there.”

A powerful installation in the Tate exhibition encapsulates Ono’s anti-war stance and invites people to see the world from a different perspective: ‘A HOLE’ is a huge pane of glass with a bullet hole through the centre, with an invitation from the artist to ‘Go to the other side of the glass and see through the hole.’ Maybe there is a lesson we can all learn from Yoko Ono, to look at the world from a different perspective, and view it from the other side of glass so that we can find some sense of unity and harmony.

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern until 1st September 2024: tate.org.uk