Following the tragic murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police in 2020, a tragedy which sparked widespread #BlackLivesMatter protests and heightened discussions about racial inequality and police brutality across America. Underlying race tensions were at an all-time high; some argued that the highly anticipated exhibition by celebrated Canadian-American Abstract Expressionist painter Philip Guston occurred too soon after the said event.

Satirical, painted depictions of Guston’s hooded Ku Klux Klan figures were deemed as insensitive. The curators of the show grew increasingly concerned about how these works could be perceived by the public as a promotion of the Klan rather than a critique of white supremacy. This, combined with the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, led to the decision to postpone the travelling exhibition co-organised by Tate Modern, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the National Gallery of Art Washington, and the Museum of Fine Arts Houston.

Despite the controversy, the exhibition finally debuted at Tate Modern, London, in October 2023. This is the final week to see the UK’s first major retrospective of the artist’s work in almost 20 years, which closes on 25 February.

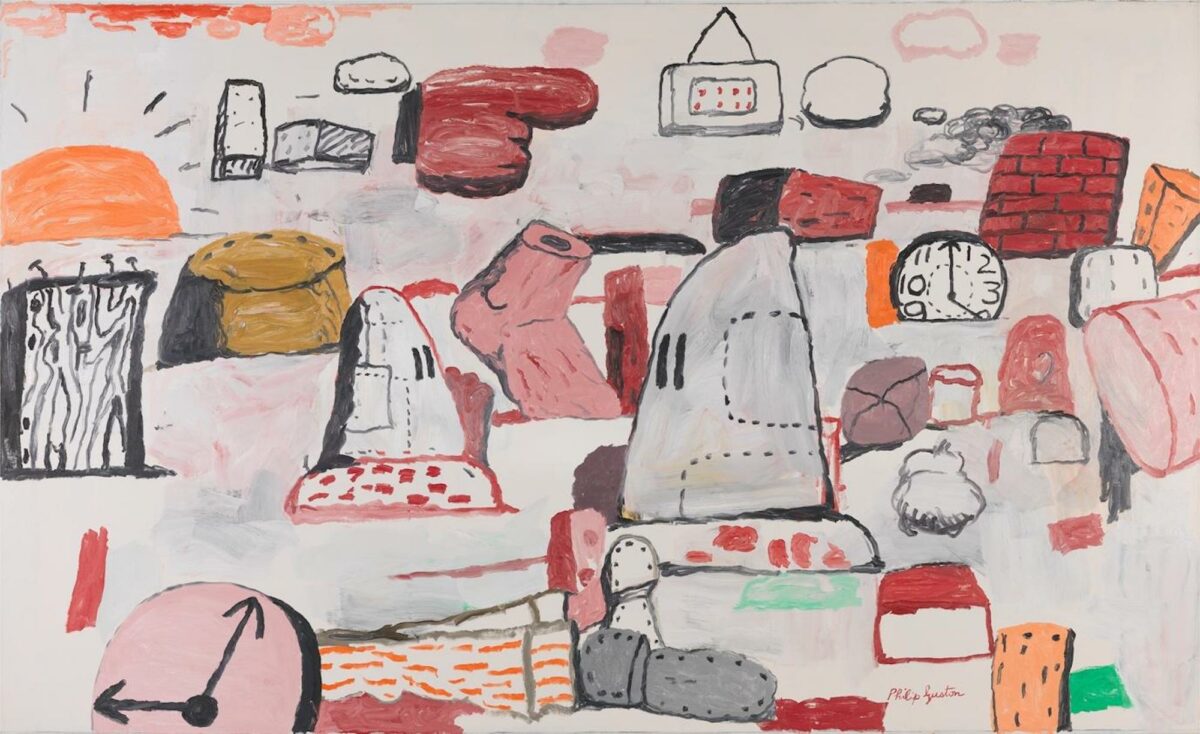

This chronological survey explores the artist’s expansive approach to painting, spanning half a decade of his illustrious career; the show includes more than 100 oil paintings and graphic drawings from figuration to abstraction and then back to figuration. Guston was born Phillip Goldstein in 1913 to Jewish immigrants who escaped antisemitic persecution in what is now present-day Ukraine. He incorporates dark, cartoonish, hooded figures as a stark indictment of racism and complicity, imbuing his work with a newfound depth and immediacy that transcends formal aesthetics in painting. Although not included in the show, a drawing he created at age 17 titled Drawing for Conspirators,1930, provides the observer with a glimpse of seeded violence depicted in a mannerist-style crucifixion. Showcasing hooded Klansmen during the lynching of two Black figures, the optics, proportions, elongated necks, and the use of black and grey graphite and sepia tones of colour pencil and crayon intensify the impact of the piece. We are looking at social commentary on events that happened not too long ago which continue to stain America’s history.

Being Jewish, he empathised with minority groups and even became involved in militant movements during the 1930s. Even though he stopped producing political art early in his career, he sustained a degree of political involvement.

Guston said about his hooded paintings after Ku Klux Klan vandalised one of his Los Angeles murals in 1933,

They are self-portraits. I perceive myself as being behind the hood. . . The idea of evil fascinated me . . . I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan. What would it be like to be evil?

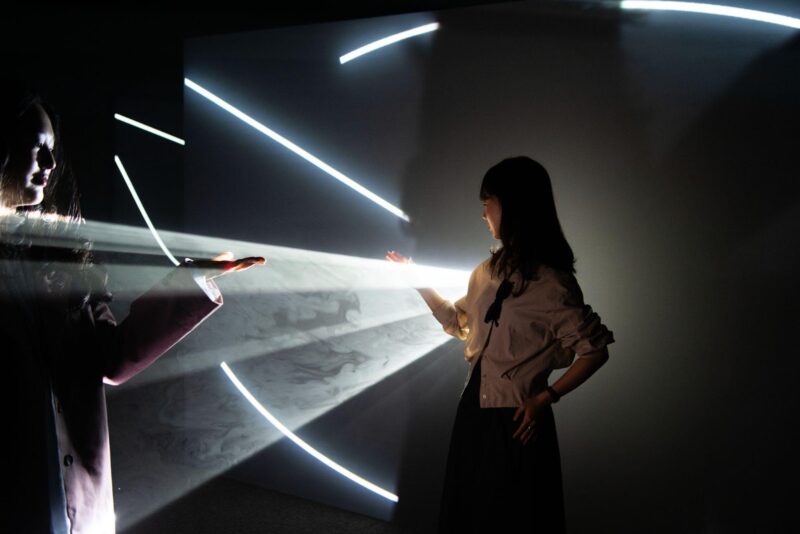

Flatlands, 1970, serves as a visual reminder of that violence, even in the absence of explicit violent actions. Instead, the artwork depicts a busy image of Klansmen going about their day wearing patched hoods surrounded by everyday objects, decapitated limbs without a body, clocks, and other surreal items. Guston’s proclivity for social justice and his commitment to further reinforcing anti-racist narratives through imagery that openly opposed the Ku Klux Klan. He wanted to challenge the ideologies promoted by such groups and the powers which uphold them.

We witness the genesis of the canonical abstract art that established his reputation in the 1950s in the work titled Passage, 1957–1958. Acute recognisable elements of future works, his signature restricted palette of cadmium red, titanium white, black, blue and orange begin to take shape—metamorphosing in front of us.

A display of paintings with hooded figures would be unveiled at Marlborough Gallery in 1970, which infamously included The Studio, 1969. These later works were considered pivotal in modern art and showcased his technical capability and devotion to addressing societal issues. Much to the dismay of his critics and peers, Guston would eventually return to figuration and move away from abstraction by the late 1960s. He wanted to tell difficult stories centred on darker aspects of human nature — his return to figuration defied categorisation.

The Line, 1978,” is very much what we know of Guston today. A prominent flesh-coloured hand emerges from the clouds against a blue sky, drawing a line on the ground below. Guston believed that lines were crucial to the creative process —this artwork highlights the importance of lines and how they define the space.

The exhibition reflects a broader focus on the resurgence of landmark exhibitions by American Post-War artists from the twentieth century and Guston’s cohorts from the New York School across exhibitions in London and Paris, including Mark Rothko at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris and Robert Ryman. The act of looking opening in March 2024 at Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris.