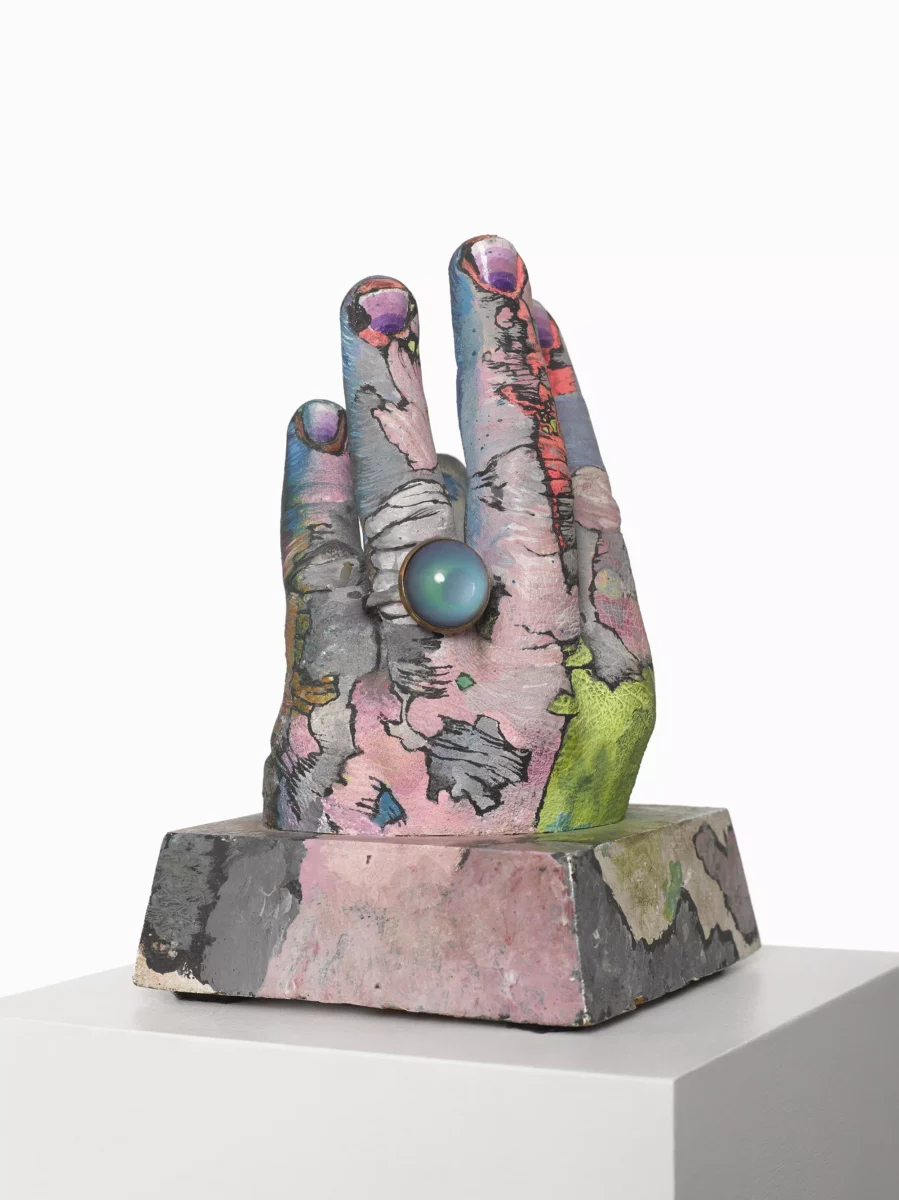

Pace has announced the global representation of the estate of legendary American artist Paul Thek. Working across sculpture, painting, and installation, Thek cultivated an entirely idiosyncratic approach to art-making that toyed with both Pop and Minimalism while rejecting the dominant strains of those movements. Best known for his Technological Reliquaries series, “meat pieces” comprising hyper-realistic wax sculptures depicting hunks of flesh—both human and otherwise—and encased inside pristine transparent vitrines, he is among the most important figures of the post-1960s generation.

We’re so thrilled to begin representing the estate of Paul Thek, who posed radical questions about what art can be and what kinds of emotional and intellectual responses it might inspire. Our exhibition of his notebooks in New York next year will shed light on how Thek worked through ideas for his sculptures, paintings, and installations, and we’re so proud to kick off a multi-year publishing project focused on his extraordinary, rarely seen notebooks with this upcoming show.

Marc Glimcher, CEO of Pace Gallery,

The gallery’s representation of Thek’s estate is a homecoming of sorts, since the artist’s second-ever solo exhibition was presented by Pace in New York in 1966. As the primary representative of the estate on a global scale, Pace will work in collaboration with the Paul Thek Foundation and The Watermill Center in Water Mill, New York, along with Galerie Buchholz in Berlin and Cologne and Mai 36 Galerie in Zürich. The Thek estate joins more than 30 artists’ estates represented by Pace, including those of Alexander Calder, Jean Dubuffet, Peter Hujar, Agnes Martin, Louise Nevelson, and Mark Rothko.

Thek, who died of AIDS-related complications in 1988, left behind more than 100 notebooks containing drawings and watercolors, diary entries, poetry, correspondences, ideas for artworks, and elaborate transcriptions of texts by philosophers or theologians. Providing unparalleled insight into his imagination, these notebooks, which Thek considered artworks unto themselves, will be the subject of a landmark exhibition presented at Pace’s New York gallery in 2025.

To date, Thek’s notebooks have been only sporadically exhibited, and most have never been seen by the public. Pace’s forthcoming exhibition—which will present nearly 100 of the extant notebooks, offering a window into the artist’s mind—will be curated by the gallery’s Chairman and Founder Arne Glimcher, who knew Thek and exhibited his work in the 1960s; the gallery’s Chief Curator Oliver Shultz, who wrote his doctoral dissertation on the artist; and Noah Khoshbin, Managing Director of the Estate of Paul Thek and Curator of The Watermill Center.

This exhibition will mark the beginning of a multi-year publication project led by Pace, which aims to make the entire contents of Thek’s notebooks accessible to the public.

I met Paul Thek in the early 60s in a small art world filled with camaraderie and collaboration. I was curating an exhibition entitled Beyond Realism that I thought would reveal the surrealist influence on the Pop artists. Paul Thek was a perfect fit. With my business partner Fred Mueller, who had recently seen the work, we visited the studio. There are rare moments when I have been astonished to experience something I’d never seen before. This was one of them. In process on his worktable were two meat pieces glistening with layers of fat and bristling with human hair. I was totally transported and thought the meat was real, and I actually thought I smelled it. We talked for hours about the works he wanted to make encased in complex Plexiglas vitrines and tall Formica reliquary column

Being part of something great is a rare gift. We immediately agreed to finance his production and in the months that followed I worked very closely with Paul to find technicians capable of his demands. We became close friends, and I supervised the construction of the reliquaries that would become his solo exhibition at Pace in 1966. It is very significant for Pace to represent the Paul Thek estate and I look forward to collaborating with Robert Wilson, Noah Khoshbin, and Oliver Shultz on the forthcoming exhibition of the artist’s notebooks in 2025. There are surprises and discoveries to be made!

Arne Glimcher, Founder and Chairman of Pace Gallery,

Pace Gallery gave Paul Thek his first support in the 1960’s. It was foundational for him. That legacy continues. No other gallery has the history, the heartfelt passion, and the academic scholarship in terms of Paul’s life and work. Paul said the following in one of his notebooks: ‘I think my time will come so I don’t want to FORCE it, or push it, because then it will come and then be OVER, so I’d rather wait longer and perhaps enjoy it more.’ Executor Robert Wilson and I feel strongly that Pace Gallery, along with our other partners, not only will be the best stewards of Paul’s legacy, but will be a collective catalyst expanding Paul’s vision into the future. This is, very truly, Paul’s time

Noah Khoshbin, Managing Director of the Estate of Paul Thek and Curator of The Watermill Center,

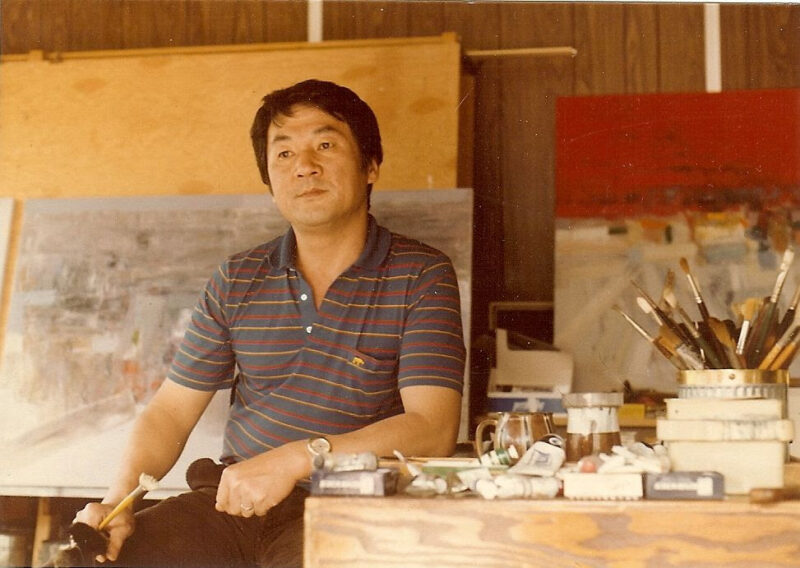

Born George Thek in Brooklyn, New York in 1933, the artist grew up in the borough’s Sheepshead Bay neighborhood. He studied at the Art Students League, the Pratt Institute, and Cooper Union School of Art in the early 1950s. Moving to Miami in 1954, Thek became part of an artistic circle that included set designer Peter Harvey; photographer Peter Hujar, who would become Thek’s boyfriend; and writer Tennessee Williams. His letters from this period reveal that he began referring to himself as Paul in the mid-1950s.

Later that decade, Thek returned to New York with Hujar. He exploded onto the city’s cultural scene in 1964 with his first solo exhibition at Eleanor Ward’s Stable Gallery, which featured Thek’s disturbingly realistic wax depictions of human flesh—replete with layers of sinew, skin, fat, and hair—that he displayed in glass boxes resembling minimalist sculpture. The show was a sensation that catapulted Thek to the forefront of the New York art world.

Following a studio visit with the artist, Pace Gallery Founder and Chairman Arne Glimcher included one of Thek’s early meat pieces in the 1965 group exhibition Beyond Realism. Presented in New York, this show also featured work by Richard Artschwager, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Morris, and Lucas Samaras. Thek’s second-ever solo exhibition was presented by Pace the following year. One of only three solo shows he would have in New York throughout the entirety of the 1960s and 1970s, his Pace exhibition showcased a new body of meat pieces, which would become his most famous works of this kind. He would later come to refer to these as his “Technological Reliquaries,” a term that is now used to describe all of Thek’s meat pieces. For his show at Pace, Thek encased the “sadistic geometry” of his abject chunks of butchered flesh inside elaborate enclosures made from colored Plexiglas and melamine laminate. Glimcher helped Thek realize these works by setting him up with Louise Nevelson’s Plexiglas fabricator.

An earnest statement of posthuman embodiment and a critique of prevailing trends in contemporary art, Thek’s Technological Reliquaries series also reflected his profound Catholic religiosity. Inspiration for the meat pieces came from the artist’s 1963 trip to the Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo with Hujar.

There are 8,000 corpses—not skeletons, corpses, decorating the walls, and the corridors are filled with windowed coffins,

Thek later said of the experience.

I opened one and picked up what I thought was a piece of paper; it was a piece of dried thigh. It delighted me that bodies could be used to decorate a room like flowers. We accept our thingness intellectually, but the emotional acceptance of it can be a joy.

Thek also maintained a friendship with Andy Warhol during the 1960s, and he was photographed by Warhol as part of the series Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys. Thek acquired one of Warhol’s Brillo Box sculptures—which had debuted at Stable Gallery in 1964—and repurposed it into a work of his own by turning it on its side and filling its interior with a glistening block of bloody, sinewy flesh. This work, Meat Piece with Warhol Brillo Box (1965), perfectly embodies Thek’s critique of the disembodied aesthetics of both Pop and Minimalism, and it is now in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

In 1967, following the Pace exhibition, Thek realized his most infamous work, The Tomb (1967), also known as The Death of a Hippie or, simply, Dead Hippie. Once again using wax, the artist cast his own body parts to create a facsimile of himself, which he presented as a ritual corpse—lying prone on the ground, dressed in a suit, fingers severed and placed in a pouch around the figure’s neck—inside a small wooden ziggurat that he constructed inside the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

Widely interpreted as a rebuke of the Vietnam War, this piece caused an uproar and briefly brought awareness of Thek’s work into the mainstream. Shortly after the exhibition at the Whitney Museum, Thek left New York for Europe, where he would live for most of the following decade. The wax figure at the center of the The Tomb was exhibited several more times throughout the 1970s in exhibitions that Thek staged at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1969, the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 1971, and Documenta in 1972, among other venues across Europe. The work was publicly displayed for the last time in the Westkunst exhibition at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne in 1981, after which it was lost. Considered one of the most important examples of American art of the 1960s, The Tomb is no longer extant today.

While living in Europe in the 1970s, he pioneered a new mode of exhibition making that involved the creation of elaborate, ephemeral installations—Thek’s ideas for these works are well documented in his notebooks from this period. Haphazardly composed of sand, candles, newspaper, chicken-wire, polaroid photographs, discarded furniture, and other varied materials, the installations were assembled into ad-hoc environments by a traveling group of artist associates that Thek called “The Artist’s Co-op.”

In 1977, Thek mounted his first large-scale American museum exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia. The artist had been awarded a National Endowment for the Arts Grant in 1976 to support the publication of the catalogue for the show. Titled Processions, this was the only solo show that he would present at a US museum during his lifetime.

In the mid-1970s and throughout the 1980s, Thek created an extensive body of paintings on newspaper that constitute a major portion of his later artistic production, since his installations were largely ephemeral and exist today only as residues, artifacts, and fragments. His use of newspaper for these works links them, on a conceptual level, to questions of time and temporality, which had always been central to Thek’s art. “My work is about time,” he wrote in one of his notebooks, “an inevitable impurity from which we all suffer.” Several of Thek’s final paintings, made in 1988, the last year of his life when he knew he was dying from AIDS, contain poignant meditations on the word “time.”

Although he had only one American museum exhibition during his lifetime, at the ICA Philadelphia, Thek is now recognized as one of the most influential and elusive artists of the second half of the 20th century. Since his death, his work has been the subject of several important museum exhibitions, including a major retrospective organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in 2010, which traveled to the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles and the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh. His works are in the collections of major institutions around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C.; the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; the Centre Pompidou, Paris; and the Museum Ludwig, Cologne, among many others.