Sean Connery had such a bad time on the set of 2003 semi-blockbuster The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen that it convinced him to quit acting for good. In the film, Sean stars as adventurer Allan Quatermain, leading around a select crew of Victorian literary icons like Mina Harker from Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray, and a copyright-issue-workaround of HG Wells’ The Invisible Man, in a quest to save the world. It’s drivel, but it’s also chock full of Victorian fantasy madness to keep it watchable. That’s the thing with the Victorian era – its iconography is so saturated in the mystique of the Industrial Revolution that it captures our imagination. When we set things against a backdrop of the newfound wonders of electricity, the telephone, Darwinian theory, steam travel, photography, X-rays and the flushing toilet, we’re in for a treat.

Spread across four rooms of the Djanogly Gallery in Nottingham, this exhibition looks to serve up that treat by evaluating how the Victorian legacy maps onto our present day. The first room aims to tackle colonialism at the height of the British Empire, confronting you from the off with Major General Andrew Gilbert Calls a Drone Strike on his Leek Phone ™, Magersfontein, 11th December 1899, Southern Africa, 2020, Andrew Gilbert’s satirical sculpture of an Anglo-Zulu war era British soldier complete with red jacket and white pith helmet. Tea bags hang off the uniform and in the soldier’s left hand sits a mobile phone, which going by the artwork’s title, is for calling in air strikes. Yinka Shonibare’s globe-headed mannequins also use the iconography of Victorian sartorial history to explore colonial imagery, their bodies draped in kitschy frilly attire covered with his signature African patterns. A not-so-subtle yet eye-catching start.

Next are up there are sets of photographs by Sunil Gupta and Heather Agyepong. Gupta’s images borrow compositions from famous pre-Raphaelite paintings to explore LGBTQ+ rights in his native India, using his friends and fellow activists as models. Agyepong reimagines portraits of Lady Sarah Forbes Bonetta, the West African goddaughter of Queen Victoria, inserting herself as Bonetta. With ethereal window light streaming through, Gupta’s reinterpretation of Henry Wallis’ iconic The Death of Chatterton projects a playful allure, and Ayepong’s self portraits show a well-realised vulnerability.

Room two shifts focus onto unsung female naturalists of the period. This includes a series of gelatin silver prints by Mark Dion and J.Morgan Puett that depict amateur female scientists played by leading contemporary figures in the British art scene. Following the previous room, this technique of substitution to right historical wrongs, however noble its cause, wears a bit thin. As always though, Florence Nightingale is here to save the day. Her childhood collection of gleaming seashells, displayed in their original drawers take on a poignancy in the context of her pioneering achievements.

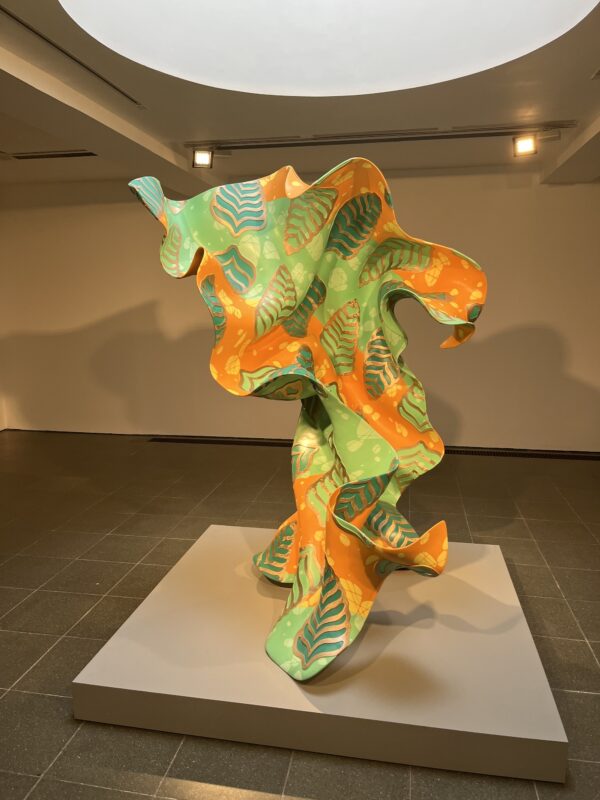

The last two rooms are busier and go further in indulging the Victorians’ penchant for spectacle. Taking centre stage, Kate MccGwire’s luxuriant, winding feather sculpture works as an exercise in unabashed formalism, but it’s Polly Morgan’s taxidermied squirrel curled up into a champagne glass that sticks in the mind. Its eyes closed and body flowing over the edge of the glass, it’s a pathos-tinged wonder that inhabits a genuine sweetness and manages to create something fresh from a quintessentially Victorian craft. We’re on a roll here, topped by Tessa Farmer’s intricate floating biological tableau of nano-sized fairies battling each other atop all manner of bones, plant roots, birds, snakeskins and chunks of Portuguese Man O’War. It’s almost Bosch-like in its gothic chaos, and its fragility is enough to break even the most seasoned of art couriers into a cold sweat.

There are some missed opportunities in this show. As the pioneers of photography and various immersive optical delights, the Victorians would’ve jumped at the chance to experiment with all the emergent digital technologies that are currently shaping our future. There’s some Photoshop-ing on display here, but that software is over 30 years old now, so where’s the engagement with AI, VR and AR? Overall though, this is a thoughtful and well-researched exhibition that demonstrates and gives us insight into how Victorian Britain’s history and iconography continues to serve as a source of inspiration and contextualisation for artists.

The Victorian legacy is so wrapped up in a distilled form of its own imagery that it makes you think about the idea of legacy itself. What’s worth preserving and what’s best to discard. As a boy, I associated places with specific eras; if France was 1980s Citroën futurism and Italy was Caravaggio Baroque, then Britain was undoubtedly Victorian. Reductive, I know – kids eh? That last one though, it still rings true. It was an age of such expansive change that it still permeates almost every facet of this island, leaving us with clues about how to manage incoming change. This show can act as a reminder of that.

REIMAG(IN)ING THE VICTORIANS – 7th January, Various times, Djanogly Gallery