One sculpture includes a photograph of an astronaut in space next to a plastic snorkel, a mischievous placement. Both look close to falling. Oxygen devices – life-giving – are cheap plastics and no human feat worth applauding. There is no human feat worth applauding.

A tiny figurine crosses the terrain of a wedding hat, an action movie still image without a story. The wedding hat sits on top of a fallen mannequin. Another movie still. The mannequin sculpture series is called Schauspieler, but these actors give out no more gestures.

The whole show can be surveilled in a glance. A flat plain, open-plan and exposed. Think of every new office block, its glass meant to signal openness, exposure to a new bright future. Instead, the office workers seem suspended mid-air, ridiculous, precarious. The sunlight reflected off the newly built 20 Fenchurch Street left a parked Jaguar a melted mess. No more purring. Genzken’s photographs of the New York skyline curl off their supporting structures, sensitive to heat and moisture.

Maybe that figurine is in the midst of a disaster movie. Avalanche, earthquake, tsunami. The waves crash through the folds of the wedding hat. Like a disaster movie Genzken’s works are a spectacle of things falling apart, of a levelling gaze that takes down the permanent with the impermanent, the expensive with the cheap, the miraculous with the ordinary. It’s the pleasure of observing complete destruction – no caveats, no ethical conundrums about what to do with what’s left. Everything is going to go so don’t worry about it, don’t think about it too much. Enjoy it.

Genzken herself is completely removed from the exhibition. The photographs of the artist pasted here and there on a sculpture seem to mischievously play with this fact – they don’t tell us much about the artist at all. The exhibition leaflet writes,

Her complex work is in constant movement, constant flux. Stasis is not an option, and through her work she always finds new ways of alarming and moving her viewers.

Yet these sculptures are still. The last work is a pile of magazines, newspapers, plastic bags. They scatter the floor. The occasional strip of tape is humorously ineffective, doing nothing to meld the pile together or to the ground. My immediate response is to kick them apart.

Because they could easily be moved but they don’t. They could provide a record of the years in which Genzken collected them – 1989 to 1991 – but they don’t. It’s nothing but stasis, the levelled ground at the end of the movie when nothing is left and everything is calm. Genzken has dropped the pile of magazines and walked away and so does everyone else. At the exit there’s a table at which a pile of the exhibition leaflets picked up on entry have been discarded. Lightly perused then left.

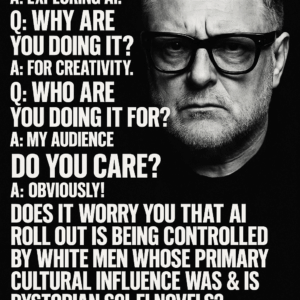

The exhibition compelled me and left me unsettled. Is it critique? Or is it the pleasure and play – and relief – of going beyond critique because the disaster has already happened? What is critique anyway? Almost all exhibition reviews work in the same mode. The disaster has already happened, and so has the exhibition. The reviewer must simply describe what that exhibition was. An authoritative review means the author’s removal from the review. Forget that this person was actually there thinking and not thinking and struggling and contradicting and confusing. Keep the use of the pronoun ‘I’ to a minimum. In an oft-quoted essay on Genzken Benjamin H. D. Buchloh writes,

To have the self succumb to the totalitarian order of objects brings the sculptor to the brink of psychosis … that psychotic state may well become the only position and practice the sculptor of the future can articulate.

The statement hums with a kind of masculine pleasure in big stakes and big talk of destruction.

Often the removal of the artist or of any kind of guiding subjectivity from a show is seen as emancipatory, as empowering the visitor to make of what they see what they will. But no exhibition or artwork or gallery is merely found, and often objects strewn to look in such a way signal the end of a disaster more than they do the way out of one.

Art can be making as well as unmaking. It can be unmaking and making and unmaking. To imagine these objects as making with what is left, or asking of them what to make with what is left, is a totally different thing from uttering – with a sigh – this is what is left.

Isa Genzken 75/75 – 27th November, Neue Nationalgalerie