One exhibition about partying is a statement. Two is a coincidence. Three makes a trend. There’s at least that many solo shows centered around disco balls and revelry on view this week across Lower Manhattan: “Party Time” by Ridgewood-based Carlo D’Anselmi at Thierry Goldberg Gallery, “Alter Ego” by Greenpoint-based Sanié Bokhari at KAPOW, and “Energy Broth” by Chinatown-based Maggie Ellis at Charles Moffett. Each exhibition marks an apotheosis within its respective artist’s practice thus far, together coalescing and harmonizing at a portent moment where the global north is really contending with whether our previous methods of functioning are amenable any longer.

All three artists were born in 1991. They were all 20 in 2011, when Britney Spears sang about dancing until the world ends and LMFAO apologized for party rocking. I don’t know if these moments were as important for these painters as they were for me, but that music’s popularity belies even more to me now than before a culture slamming Smirnoff to take the edge off, a generation starting out on the heels of a financial crisis, America’s shameful reaction to 9/11, and a swelling climate crisis. For starters. Absolutely nothing has cooled off since. Perhaps taking the edge off did not in fact solve the problem. Since then, maybe it’s gotten too real too fast, maybe the wellness girlies won, but one thing’s for sure. Fluorescents are done. The 2010s killed them. I heard theories in 2022 that the pandemic would spur another roaring twenties. Instead, inflation has skyrocketed. People are staying home. Very few in the mood. Not saying anyone should be.

“Party Time”

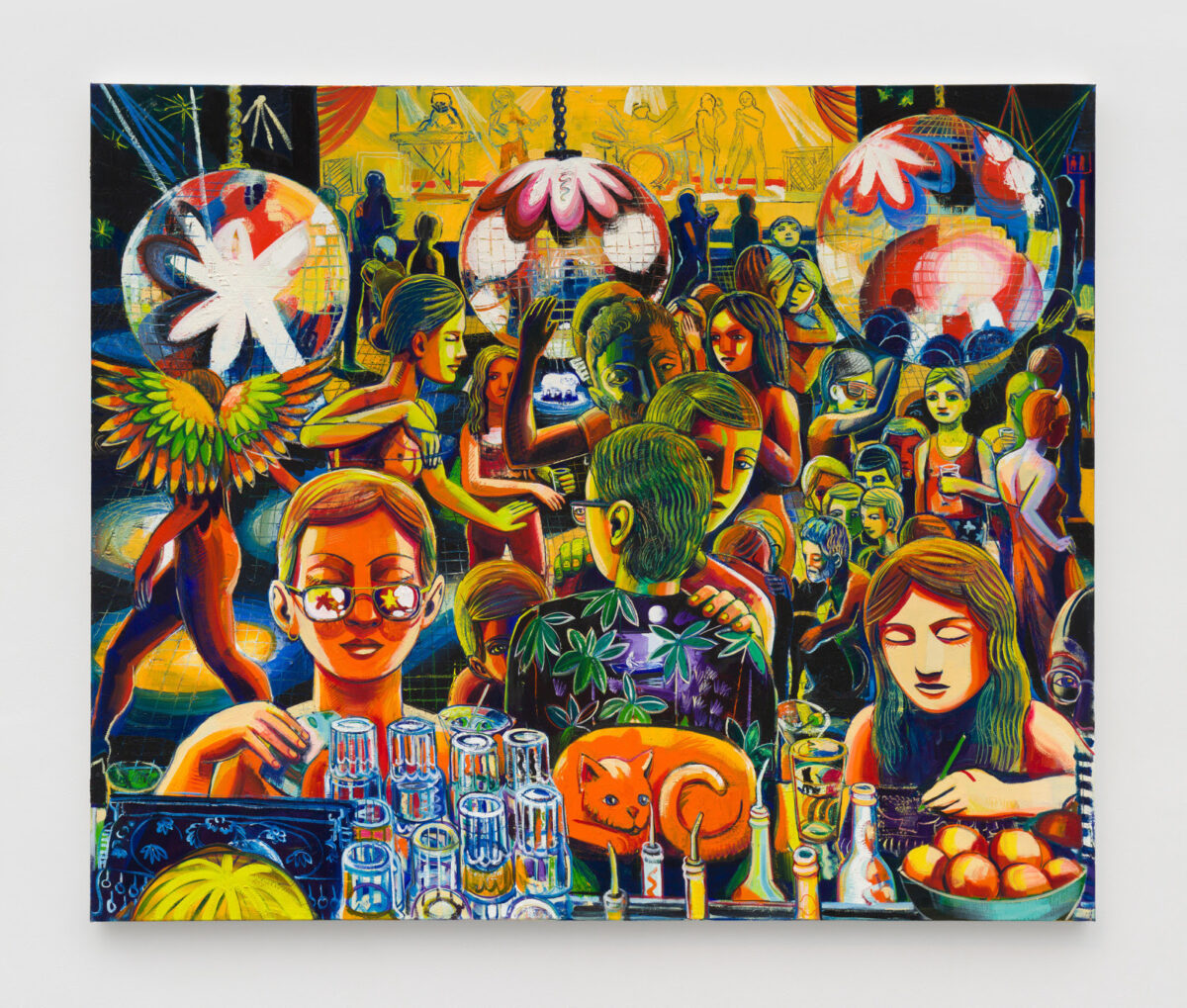

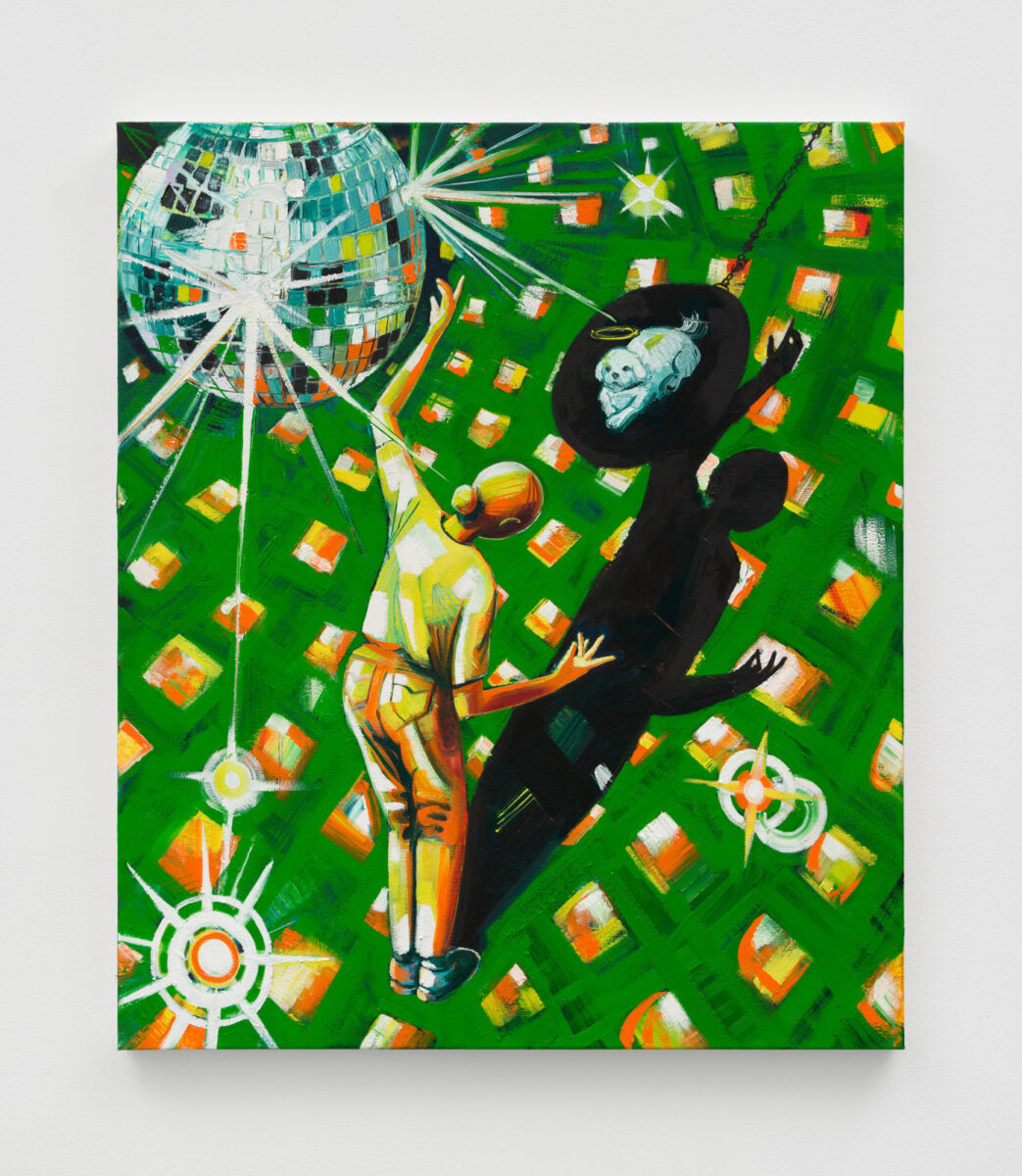

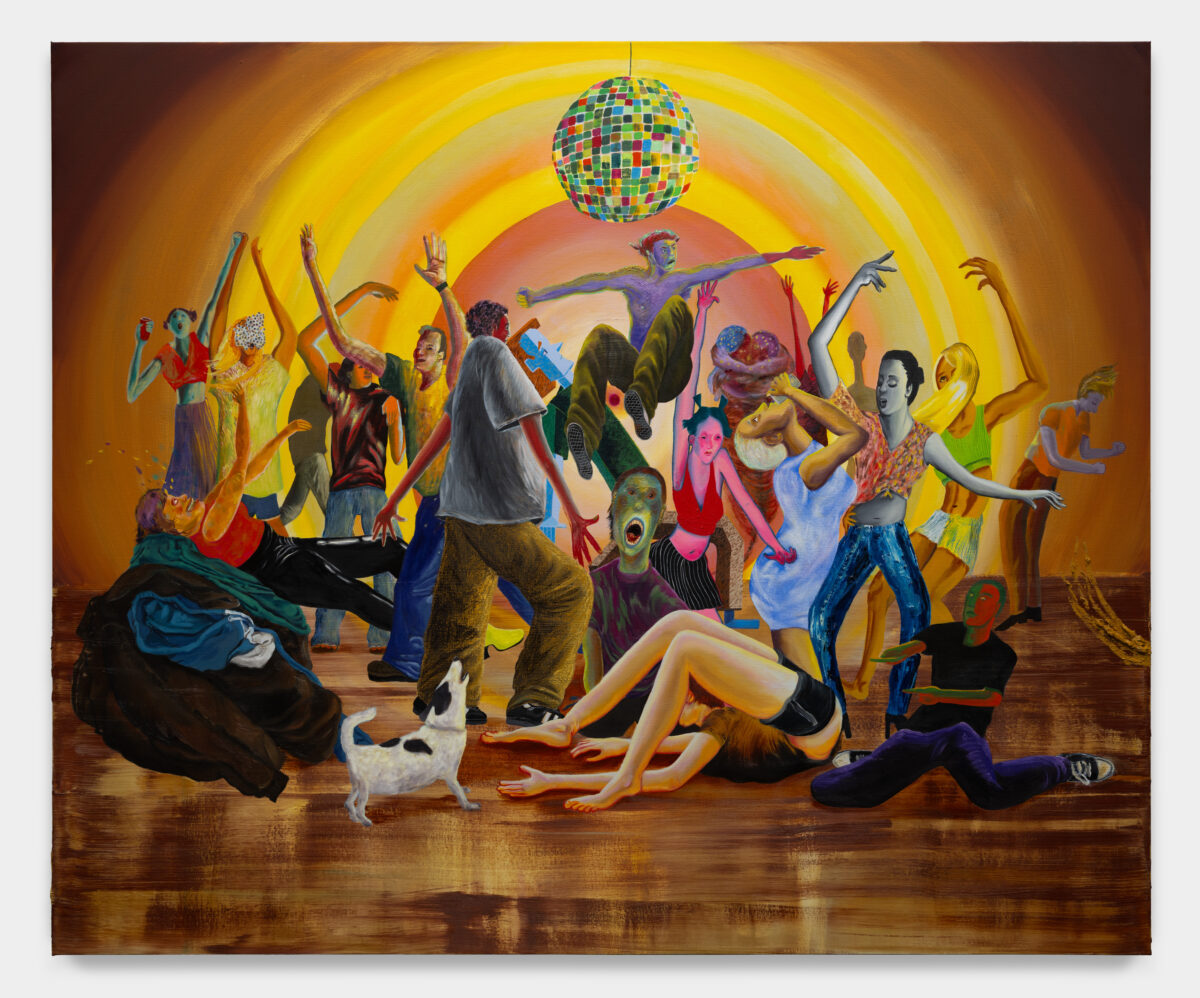

Since I met Carlo D’Anselmi in April last year, his paintings have evolved from focusing on singular figures to svelte sets of them, and now, with “Party Time,” entire raging scenes. “Now, on our Nth wave of introspective figurative painting, I really started to feel bored or tired by it,” D’Anselmi told me. “I wanted my works to focus on things that weren’t about *me*. So i began to want the occupants of my paintings to get together with each other and party and have some fun.” Canvases throughout the show depict an imaginative series of parties, from an apt Halloween gathering to a fictional scene where NASA sky trackers surrender to a last minute bacchanal before a celestial body smashes Earth. There’s even shudder shades in here. Elsewhere, D’Anselmi is more pensive — his recently deceased family dog smiles from the shadow of a girl dancing beneath a disco ball all by herself. Still, the artist refrains from taking himself so seriously. That looseness enables D’Anselmi’s archetypal wisdom to shine through his simultaneously playful, intellectual paintings.

“Alter Ego”

Acrylic, pastels, and graphite on canvas

48 x 36 in. Courtetsy of KAPOW

Sanié Bokhari’s debut show announces her arrival. She’s traveled the globe and mastered her mixed media method from all surrounding angles to arrive at these latest, moody canvases marked by shocks of bright oil paint and pastels, smeared in select spots for sensual surrealism. Bokhari returned to drawing when she moved back to Lahore after graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2018. Her scenes have since grown larger and more complex in composition and concept. “Alter Ego” presents her most involved series yet, juxtaposing the “here” and “there” of Bokhari’s disparate homes with the many selves she dons to stay afloat throughout the day. A disco ball anchors the sultry figures of “Kids In The Dark. Bokhari also reconstructed the very specimen she marveled upon from a dance floor in Lahore. Together, her disco balls commingle the phrase “Welcome” in Urdu alongside the powerful Quranic verse “In your Mercy I seek relief” in Arabic.

“Energy Broth”

Atlanta-born Ellis has historically imbued her personality-driven scenes with the patina of humanity’s grimy, animal reality, from snot rockets to nose pickers. She’s often captured community character, too, inside Olive Garden and an IMAX theater alike. As time goes on, Ellis’s premises have proven a bit more posh, particularly with her third solo show at Charles Moffett, where crowds convene in club lines, on rollercoasters, and as a fashionable scooter gang. The centerpiece, “Here For The Party,” is an anti-gravity tableaux immortalized beneath a scintillating, rainbow disco ball.

“I look for ideas for these compositions through the frescoes of Piero Della Francesca, Uccello’s battle scenes, and Bruegel’s most crowded paintings,” Ellis said. After, she continued, “I work to think of all the ways I can incorporate as many different styles of painting within one canvas. Through the complex facets of a crowd, anything is possible. Then, though the stylistic inspirations come from a broad array of Western art history, I seek out contemporary reasons groups would form.”

So, meet me under the disco ball

D’Anselmi, Bokhari, and Ellis all paint scenes that thrum from their greater sums without sacrificing critical individual components. D’Anselmi and Ellis explicitly enliven everyone in their crowds with a reason for being there. Bokhari illuminates the infinite multiplicities upholding the self. These scenes, painted over the past year in each artist’s studio, aren’t ignoring the end of the world. This time their fervor’s a route to salvation through community, transcendence through unified attention — embodied throughout in the disco ball. D’Anselmi noted such party staples “contain two extreme opposing formal ideas,” bridging the sphere and the grid, transforming darkness into excitement.

Ellis’s fascination with disco balls began when she saw revelers “twisting underneath a hot pink ball of light” at a New Years bash in Brooklyn. Then they became an excuse to play with unexpected colors. “The disco ball is a contained form but generates energy outward,” she said, adding its iconic visage is “symbolic of a chaotic good — it’s always more fun to dance and let go when you’re within this confusing and constantly changing light source rather than a static, motionless light.”

“The disco ball serves as a symbol of centrality, drawing attention from those who bask in its glow,” Bokhari said. “The imposition of Arabic script on an object like a disco ball is inherently fascinating and encourages contemplation, challenging perspectives, particularly in a Western context. As the ball spins and glistens, and the phrase rotates with it — it encapsulates the sensation of transcendence, akin to when music or art transports one to a realm that feels all-encompassing, ushering in a heightened state of awareness beyond the confines of physical reality, a journey into the present moment’s overpowering depths.”