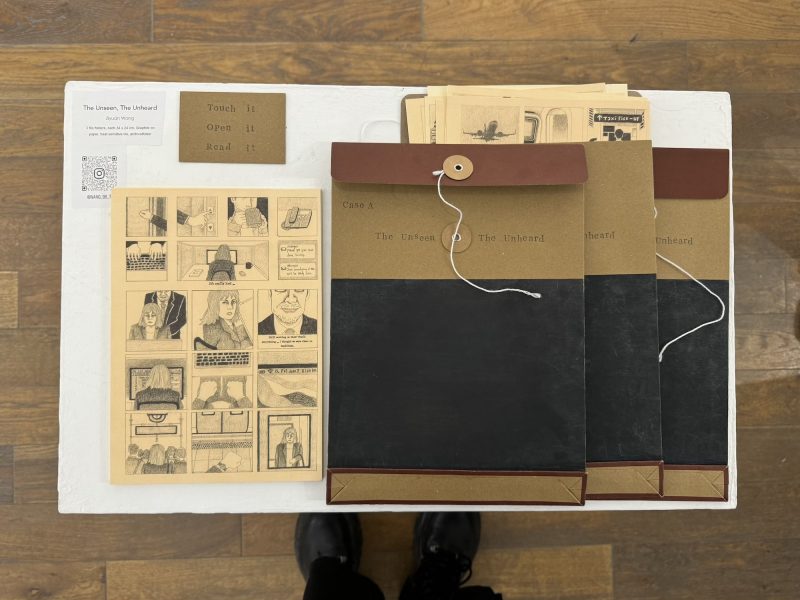

Forgeries, the female body, and wealthy English families: V&A Jameel Fellow, Dima Srouji unearths the history of Palestinian glassware in the museum’s collection

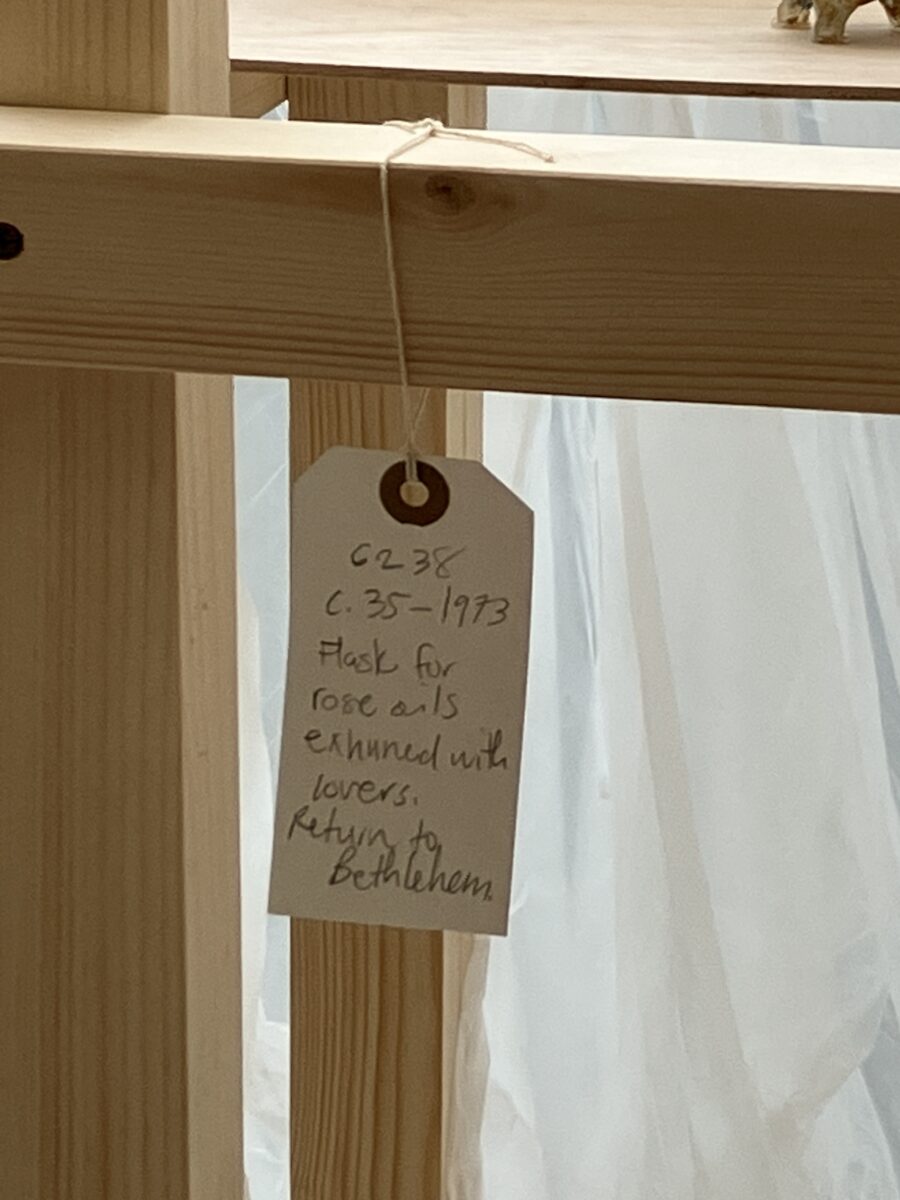

‘Flask for rose oils exhumed with lovers. Return to Bethlehem,’ reads a handwritten label. Threaded through by string, the label is tied next to a supposedly aged bulbous glass vessel.

‘Kohl bottle return to Haifa, Palestine’ reads another. This one refers to a glass vessel of a different shape: twin glass cylindrical tubes joined together, with handles flanking either side.

These are just two of the labelled eight vessels that Palestinian architect, artist, Dima Srouji presents at the V&A as part of the London Design Festival, under the poetic title ‘But She Still Wears Kohl and Smells Like Roses’.

These pieces are small enough to hold in your hand and look like artefacts; historic, prized, patinated. Only that they’re not. They’re forgeries; copies of the V&A’s original vessels. And the labels are her own speculative imaginations of what they might have been.

These glass vessels are the creative result of Srouji’s time as a V&A Jameel Fellow. Free to walk around the V&A building, and with time to research whatever she wanted, she says, ‘was incredibly overwhelming; there are thousands and thousands of pieces.’

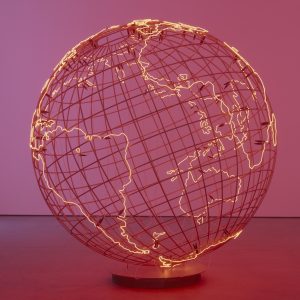

She became drawn to the collections of glassware in Greater Syria and Palestine. Initially, she planned to simply plot the objects’ history on a spreadsheet: where they came from, who donated them, and for what reason. But after a month of painstaking work, ‘what I realised’ she says, ‘is that ‘they were all kind of similar stories.’

‘All the information that we have about the pieces that were donated and gifted to the museum were gifted by incredibly wealthy English families that almost always are involved with the British military, so either a lord or someone that actually went to Palestine during an excavation as a collector, or as an officer.’

‘I realised it wasn’t really that important for me to find evidence to prove this was the history, because it was very clear that this was always going to be the case. And so it became more important for me to find a way to imagine an alternative reality for the future of the pieces rather than finding the stories from the past.’

Using these V&A original pieces as her starting point, she then decided to create perfect replicas of them. Srouji enlisted the skills Palestinian artisans she has been working with for several years; Jaba’ artisans to blow the glass, and a family in Nablus, to turn them into convincing historic copies. They still currently produce forgeries for the black market.

Such replicas of glassware sharing space with V&A artefacts, asks for a critical comparison. It asks: which objects as a society do we deem worthy? ‘Lord Salter for example would value an archaeological vessel that was exhumed in Palestine in the early 1900s. Meanwhile, you have the same craft Palestinians today are still able to make the exact same vessel. But that kind of object is not as valuable because it’s contemporary and because it’s made by Palestinians now and it doesn’t come from a British archaeologists collection.’

The history of excavating these objects, Srouji found in her research, also unearths stories of patriarchal power and the relationship between glassware and the female body. ‘There’s the women’s labour involved with excavating the vessels.

‘There are photos from the massive collection in the US Library of Congress that show you a hundred women excavating on a single site. While this white man is watching over literally as he’s standing on top of the hill. They’re also a lot of the time excavating pieces that are perfume bottles and female goddesses and cosmetic vessels that they still used.’

Then ‘the river that was used to bring sand to make glass to make the vessels. That same river is where a lot of women would go to bathe to cleanse their menstrual cycles, and go to heal different body elements. So on a molecular level, it is still very much linked to the female body.’

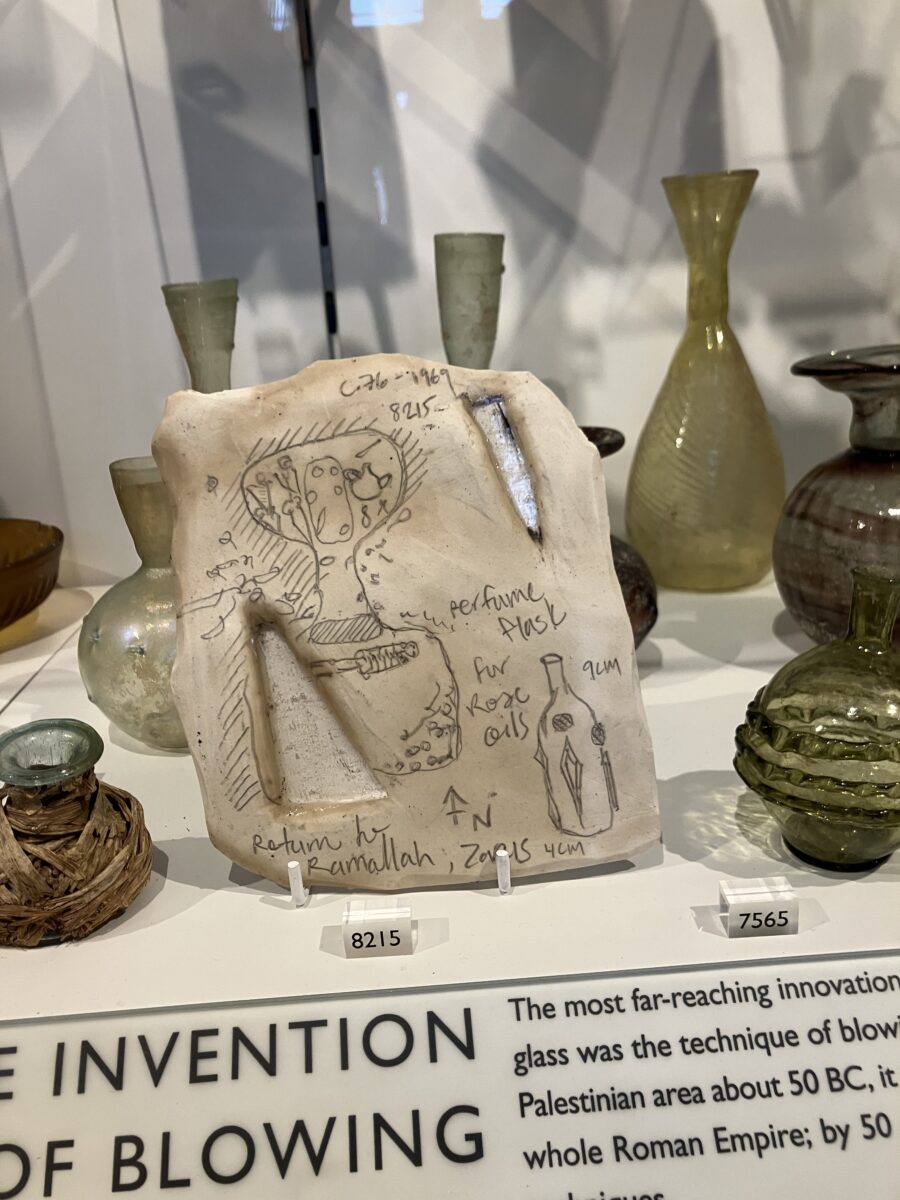

Replacing the original vessels that are usually on display, along with the glassware replicas, Srouji also inserted in their place reimagined ‘tomb cards’. Glazed, made of stone, ashen looking, Srouji etched in descriptions like: ‘stolen by Lord’, ‘Return to Ramallah’, ‘oils against the evil eye’, as well as a drawing of two skeletons together. Srouji explains that, a lot of the time, tombs in Palestine, were annotated by a [British] archaeologist, Petrie. His excavation tomb card notes would always draw the bodies that were exhumed with the excavation.

‘I always thought that the process of drawing a body is incredibly violent,’

Many of these vessels’ ‘original context is supposed to be in a stone-carved cave in Palestine, and with a body, a person that was loved by their family. And was carefully buried alongside these vessels.’

Her tomb cards, and glass vessel forgeries stay as a reminder of the context in which we engage with these vessels at the V&A today.

Dima Srouji ‘But She Still Wears Kohl and Smells Like Roses’ now until 24th September, the V&A, the contemporary glass landing, Room 131.