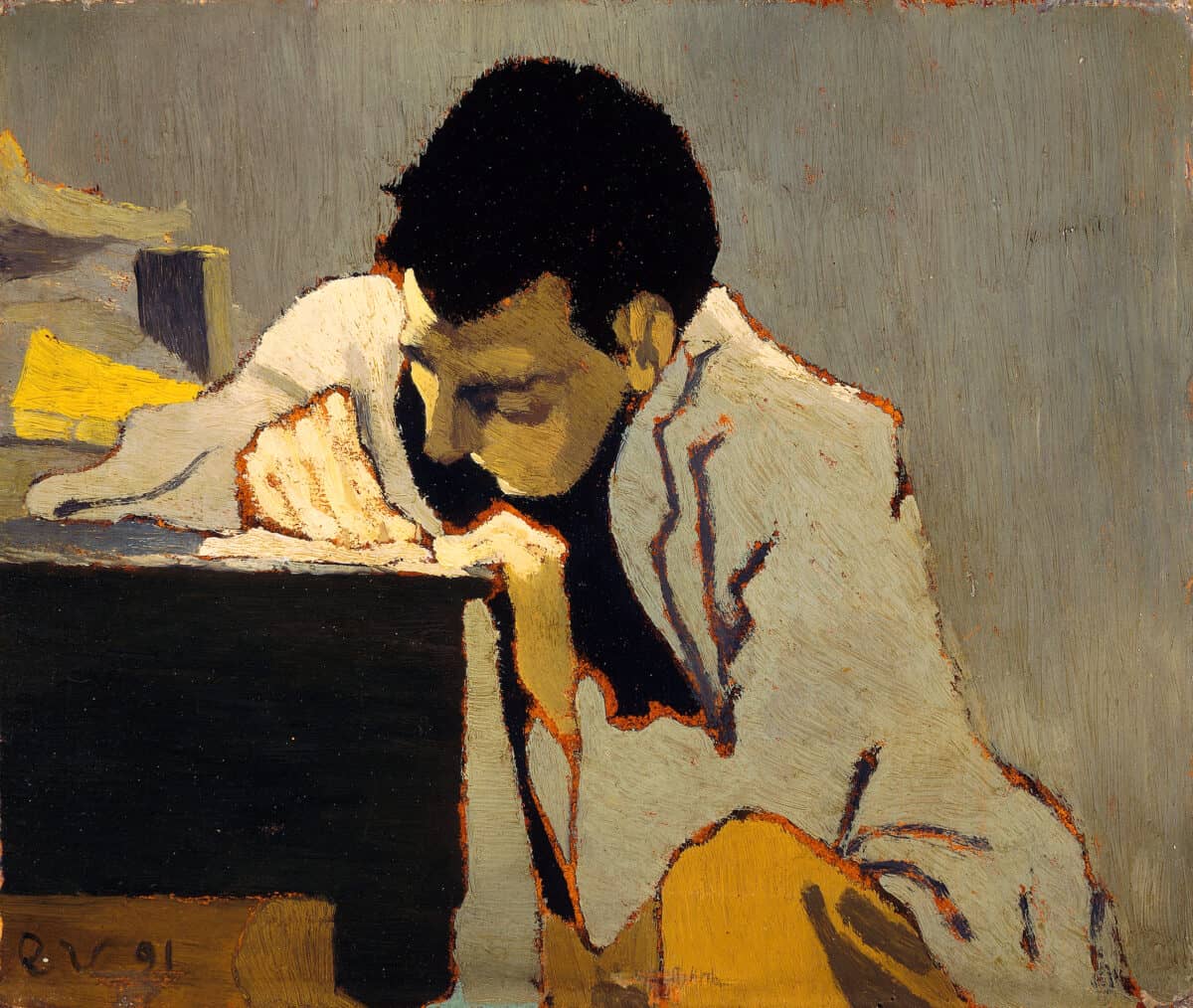

With loans from museums and private collections worldwide, After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art at the National Gallery (25th March – 13th August 2023) includes some of the most important works of art created between 1886 and 1914. While it celebrates Paris as the centre point of this new epoch, the exhibition also highlights how Impressionism’s peachy skins and blue skies echoed throughout Europe during these radical years and gave licence to generations of artists to break the rule book. Paul Cezanne, the proctor-poster boy for new boundaries of visual metonymy, put it best, writing about his process that he tried to “give the image of what we actually see, forgetting everything that has appeared before our time.” Something softens as you get older, as if life knocks the edge off you a little bit. Making my way through this exhibition—all these works are steeped in the art of the past, of the National Gallery collection’s history dealing imagistically with birth, sex, death, and the search for God—I felt that same fleeting openness to raw experience that sometimes pierces my ever-liquifying view of the world.

By the mechanical dawn of the 1900s the idea of ‘modernism’ had already glittered and expanded into disarray, stretched to a point where its original self-consciousness of tradition had evaporated into a new euphoric sense of freedom. The titans of modern art—Cezanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Degas, Munch, Rosseau—were so busy crafting a point of origin to mark a new departure, a point of a true and eternal present, they didn’t see how within fifty years that pure and vocal desire to make headway in a resistant medium, wagering on progress as they saw it where their battle cry was towards, would be hijacked by capitalism’s own desire to find an excuse to generate quickly, cheaply and carelessly.

These early experiments in modern art, where the materiality is calling attention to itself, reveal the medium of open process. Where before brushstrokes disappeared indefinably into a larger whole, now the act of painting and your own act of looking at it collapses in an immediate gesture. It’s here that modernism emerges as something born out of a hallucinogenic logic; unified, where all perceptions are appearing at once, where colour and shade and light are uprooted in a state of constant decreation; places cease to be places but frames for artists like Cezanne and Degas to depict shape and reflection and movement (whether that is the movement of modernism or just a branch caught in a sea breeze is sometimes, beautifully, hard to decipher)—what is one without the other?—visions of utopia start in the vein of a leaf and, as skies envelope towards evening, what starts as detail disintegrates into formlessness in the acerbic painted moment.

Some might say the mystery of the artist has been lost—the sketch lines visible, the artist has now shown themselves in their work—but wavering pencil lines and brush strokes radiate a certain sensitivity, like a layer has been peeled away from a more ‘finished’ work to reveal the strings behind the scenes. And as anyone who’s gone through the unvarnished doors of perception and seen the sketch lines of the universe knows, this might initially appear (with all of its controversial connotations) ‘primitive’, but contains a sort of spiritual resilience, an uprightness, amid the general flux and flex. The wider world will always be a mess, but we can sometimes have a radically different kind of experience around art: we can get on top of a problem and bring order to chaos in a way that we rarely can in any other area of life.

The impressionists’ hesitant steps through urban strangulation—landscapes tormented by the vertical and horizontal in a recess of conventional perspective where everything seems to be sliding or rising, existing in borderlands—became a touchstone for the next century of restless, stubborn visionaries to steep themselves in before creating their own idiosyncratic songs of innocence and experience (curator’s now often have the idea to impose a political radicalism onto their favourite art history titans when really it was their radicalism of style that then led to inspiring radical political thinkers—some personal favourites not included in this exhibition that rush to mind are Maria Lassnig and Stan Brakhage).

Over a hundred years after they first painted, some of these artists have become sacred to a lot of people, their ‘visions’ talked about with the same severity that people refer to the Saints, giving meaning to their life by lending meaning to the world

If all this feels a bit aggrandising, I’d have to agree, but placed in front of a Cezanne if you let your mind go very wide, drop back, and look for who is doing the looking, suddenly the semantics of style all start to fade away.

After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art, 25th March – 13th August 2023, The National Gallery