Ai Weiwei opens Making Sense at the Design Museum London.- Ai Weiwei, one of the world’s most celebrated and recognisable living artists, has unveiled a major new exhibition at the Design Museum

Ai Weiwei: Making Sense is the artist’s very first exhibition to focus on design and architecture, and is his biggest UK show in eight years.

The exhibition features works never shown before in the UK, as well as major new pieces displayed for the very first time. Large-scale works are also installed outside of the exhibition gallery, in the museum’s free-to-enter spaces, as well as outside the building.

Known around the world for his powerful art and activism, Ai Weiwei works across many disciplines: his practice encompasses art, architecture, design, film, collecting and curating. In this exhibition, Ai uses design and the history of making as a lens through which to consider what we value.

At the heart of the exhibition are a series of major site-specific installations. Hundreds of thousands of objects are laid out on the floor of the gallery in a series of five expansive ‘fields’. These objects — from Stone Age tools to Lego bricks — have been collected together by Ai Weiwei since the 1990s, and are the result of his ongoing fascination with artefacts and traditional craftsmanship. These collection-based works have never been brought together before. Three of the fields have been created for this exhibition and are seen for the very first time. The other two have never been on show in the UK before.

The five field works are:

Still Life. 4,000 tools dating from the late Stone Age are laid side-by-side as a reminder that the origins of design are rooted in survival. These axe-heads, chisels, knives and spinning wheels are presented as a terrain of forgotten know-how.

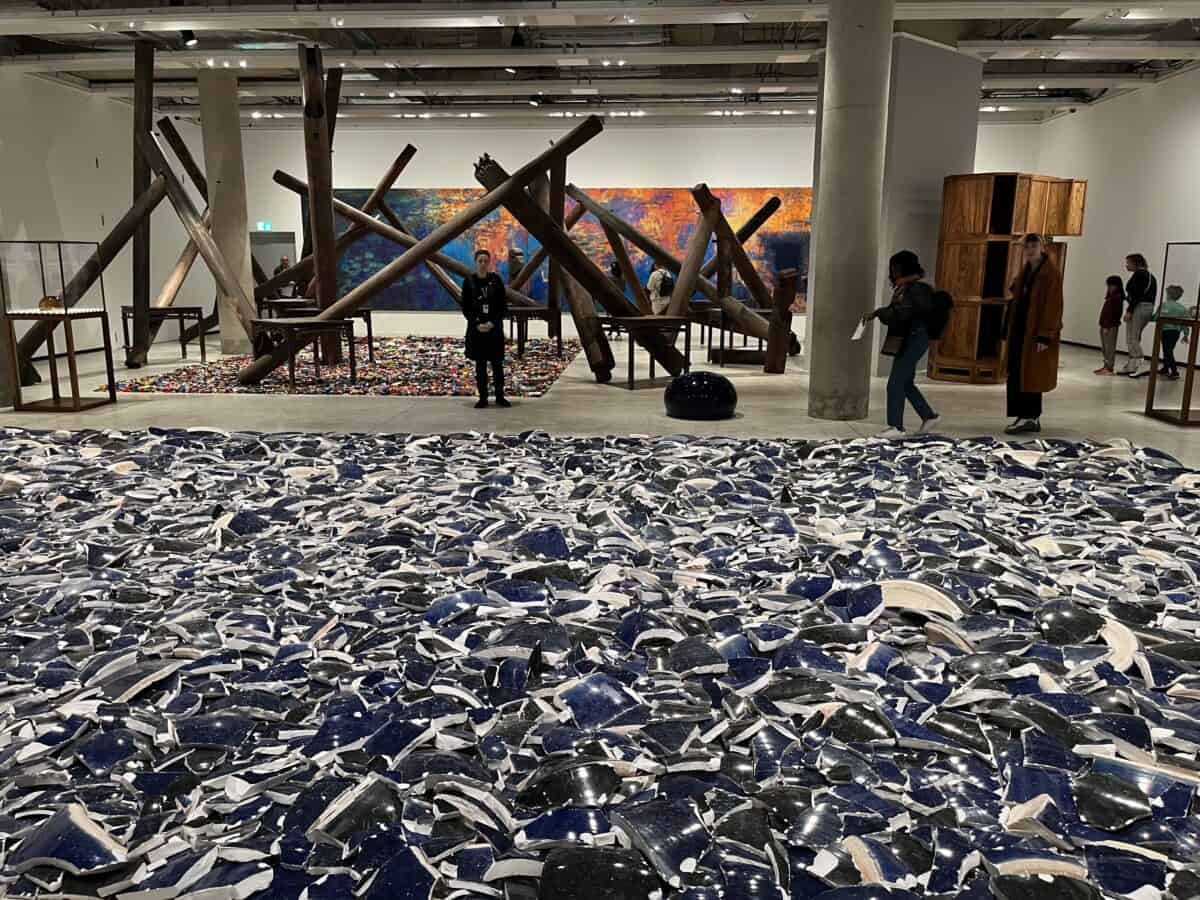

Left Right Studio Material. This consists of thousands of fragments of the remains of Ai’s porcelain sculptures that were destroyed when his ‘Left Right’ studio in Beijing was demolished by the Chinese state in 2018. The remains are a form of evidence of the repression that Ai has suffered at the hands of the Chinese government, as well as a testament to his ability to turn destruction into art. This field is being displayed for the first time.

Spouts. This field features more than 250,000 porcelain spouts from teapots and wine ewers crafted by hand during the Song dynasty (960 – 1279 CE). If a pot was not perfect when it was made, the spout was broken off. The quantity bears witness to the scale of porcelain production in China a thousand years ago.

Untitled (Porcelain Balls). These cannon balls were made during the Song dynasty (960 – 1279 CE) from Xing ware, a high-quality porcelain. Ai was struck by the fact that this precious and seemingly delicate material was once used as a weapon of war. Around 200,000 are on display, and the artwork has been created especially for this exhibition.

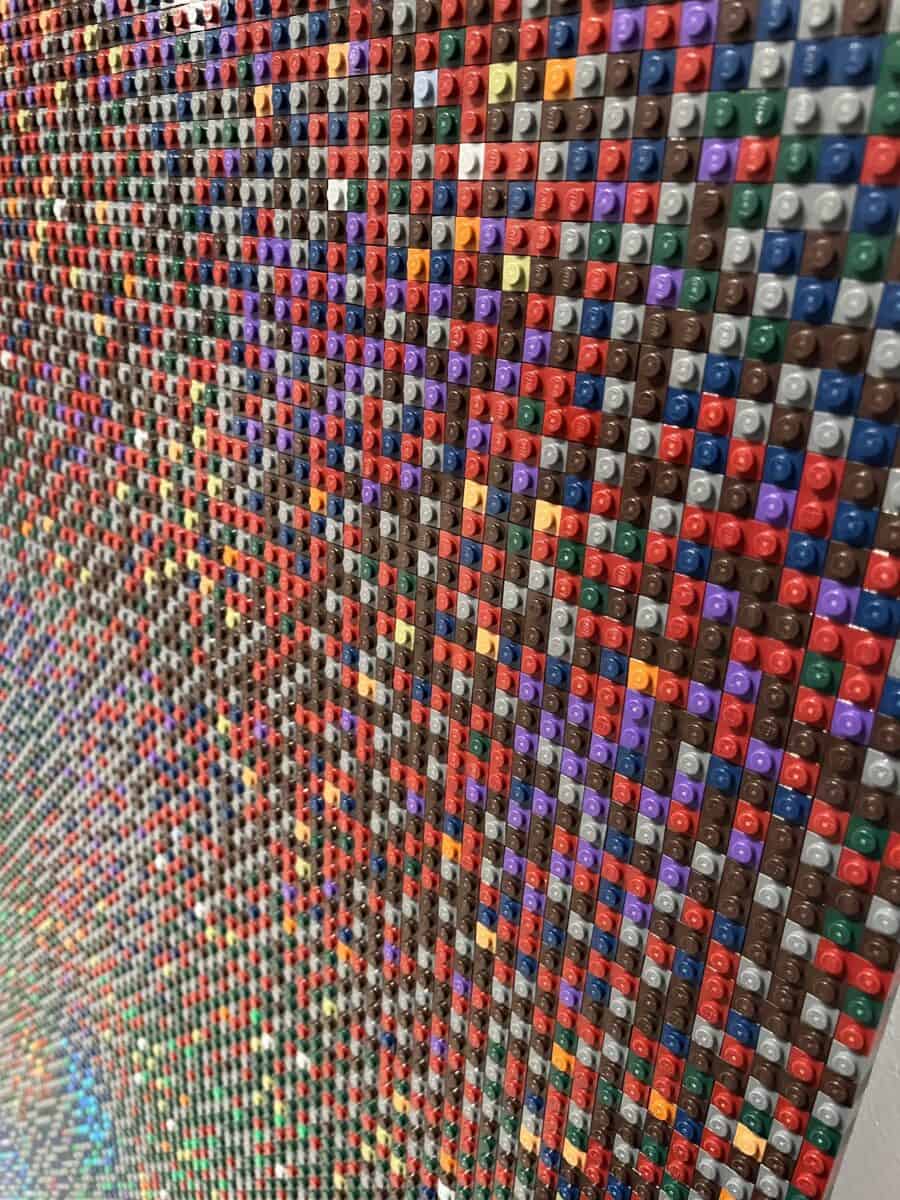

Untitled (Lego Incident). Like other objects in the fields, Lego is produced on an industrial scale, but it is machine-made as opposed to hand-crafted. Ai started working with this material in 2014, to produce portraits of political prisoners. When Lego briefly stopped selling to him as a result, his response on social media led to overwhelming donations of bricks from the public. These donated bricks are presented for the first time as a fully-formed artwork.

Presented with these vast fields, visitors are invited to make sense of them. They are able to walk among them, encountering thousands of years of human ingenuity.

Ai Weiwei’s fields are extraordinary, and they tell a story of human ingenuity that spans millennia. The fields are a meditation on value – on histories and skills that have been forgotten, and on the tension between the industrial and the handmade. Their scale is unsettling and moving, and in trying to make sense of these works the visitor is challenged to think about what we value and what we destroy.

Justin McGuirk, Chief Curator at the Design Museum and curator of Ai Weiwei: Making Sense

Alongside the fields are dozens of objects and artworks from throughout Ai Weiwei’s career that explore the tensions between past and present, hand and machine, precious and worthless, and construction and destruction. His Han dynasty urn emblazoned with a Coca-Cola logo, which is on show here, epitomises these clashes.

Highlights also include a number of examples of Ai’s ‘ordinary’ objects, where he has transformed something useful into something useless but valuable. He does this by crafting items in precious materials. These include a worker’s hard hat cast in glass which becomes at once strong and fragile, and a sculpture of an iPhone that has been cut out of a jade axe-head.

There are also works that reference the Covid-19 pandemic which exposed our dependence on humble things. On display are three toilet paper sculptures: two life-size rolls (one in marble and one in glass) as well as a 2 meter-long sculpture in marble which is being displayed for the first time. These works are all shown in the context of China’s rapidly changing urban landscape, which Ai has documented through photographic and film works, some of which are shown in the exhibition. The scale of demolition during the development boom in China over the last three decades is the backdrop to questions about aesthetic sensibilities that have been lost with modernisation.

Revealed for the first time to coincide with the show’s opening are new versions of Ai Weiwei’s famous Study of Perspective series, in which he flips the finger at iconic landmarks. Power, as embodied by culturally and politically significant sites, is Ai’s target in the longstanding series. He repeatedly performs a scornful gesture, subverting the traditional artistic method for measuring perspective. In doing so, he rejects the expectation that these institutions should be respected or revered. Begun in 1995 as a series of photographs, these have been turned into pigment prints for this show, using what Ai sees as the more graphic language of design. The twelve here are presented for the first time, and feature Ai showing his middle finger to locations such as Tiananmen Square in Beijing, and Trump Tower in New York City.

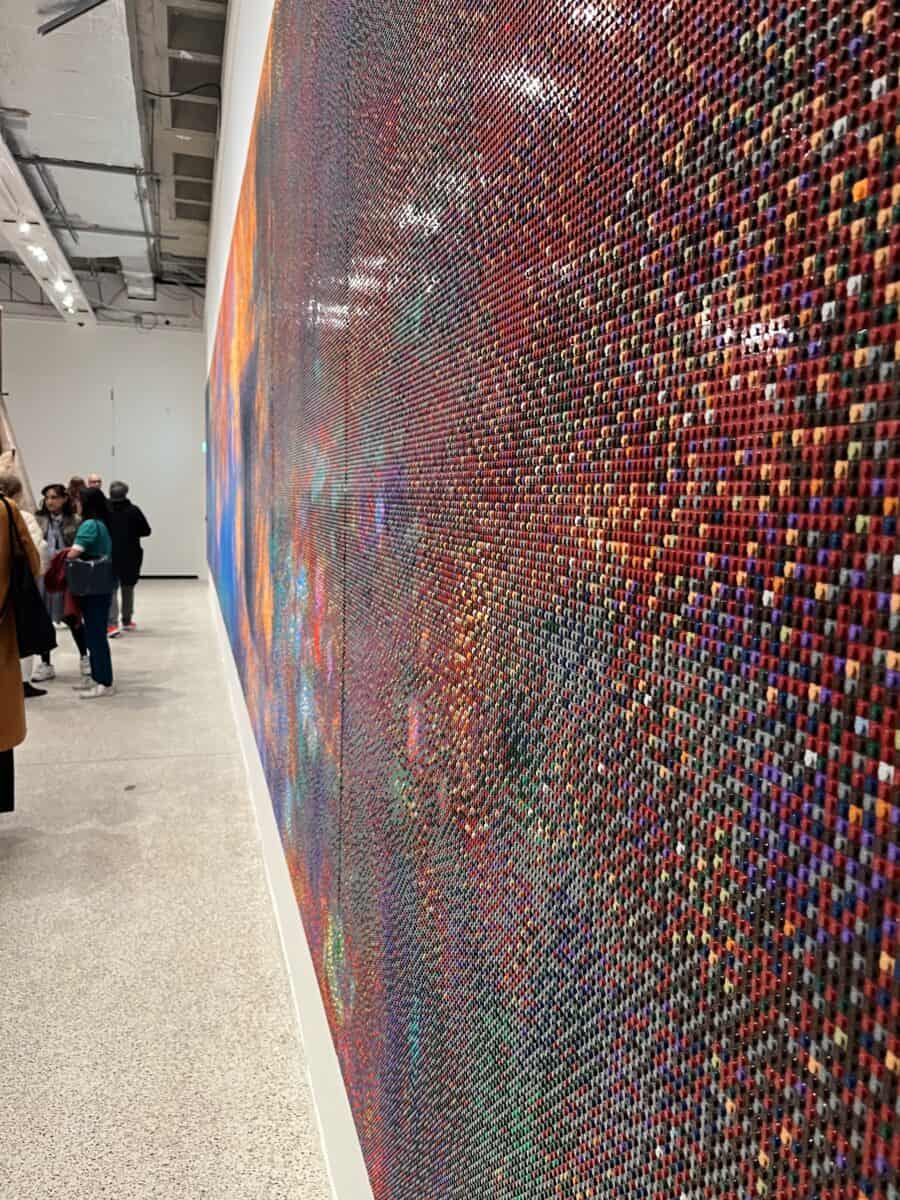

Another highlight of the exhibition is the largest Lego artwork Ai Weiwei has ever made. Constructed entirely of Lego blocks, the work is a recreation of one the most famous paintings by French Impressionist Claude Monet. Titled Water Lilies #1, the work is over 15m in length and spans the entire length of one of the walls in the Design Museum gallery. It is made from nearly 650,000 studs of Lego bricks, in 22 colours. Water Lilies #1 recreates Monet’s famous painting, Water Lilies (1914 — 26), a monumental triptych which is currently in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This vast new image by Ai Weiwei is seen in public for the very first time in the exhibition.

A number of large-scale works are also installed outside of the exhibition gallery so that all visitors to the Design Museum are able to experience Ai Weiwei’s work. The most striking is Coloured House, the timber frame of a house that once belonged to a prosperous family in Zhejiang province, in eastern China, during the early Qing dynasty (1644 – 1911 CE). It has been installed in the Design Museum’s atrium where visitors can walk within it. Ai Weiwei has painted the house with industrial colours, combining ancient and modern, and has installed it on crystal bases – giving presence and status to this unlikely survivor. This is the first time Coloured House has been seen in the UK.

This is an exhibition focussed on a very specific concept: design. I had to think about how we use the space in the Design Museum as a whole, and the exhibition offers a rich experience of what design is, and how design relates to our past and to our current situation.

Ai Weiwei

To coincide with the exhibition, Avant Arte has collaborated with Ai Weiwei to make his work available to all in support of the Design Museum. The partnership encompasses Middle Finger, a new interactive online work by Ai Weiwei and a series of limited editions.

Ai Weiwei is one of the most compelling artists and activists working today, but his practice is profoundly pluralistic, encompassing film, architecture, design and collecting. This exhibition is, therefore, long overdue and I’m proud that the Design Museum is the first institution to frame the work of Ai Weiwei through the lens of architecture and design and to collaborate in new ways with one of the great creative forces of the 21st century to date.

Tim Marlow, Director and CEO of the Design Museum,

Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, Design Museum, 7th April to 30th July 2023.

Curated by Justin McGuirk, Chief Curator at the Design Museum and Rachel Hajek, Assistant Curator at the Design Museum