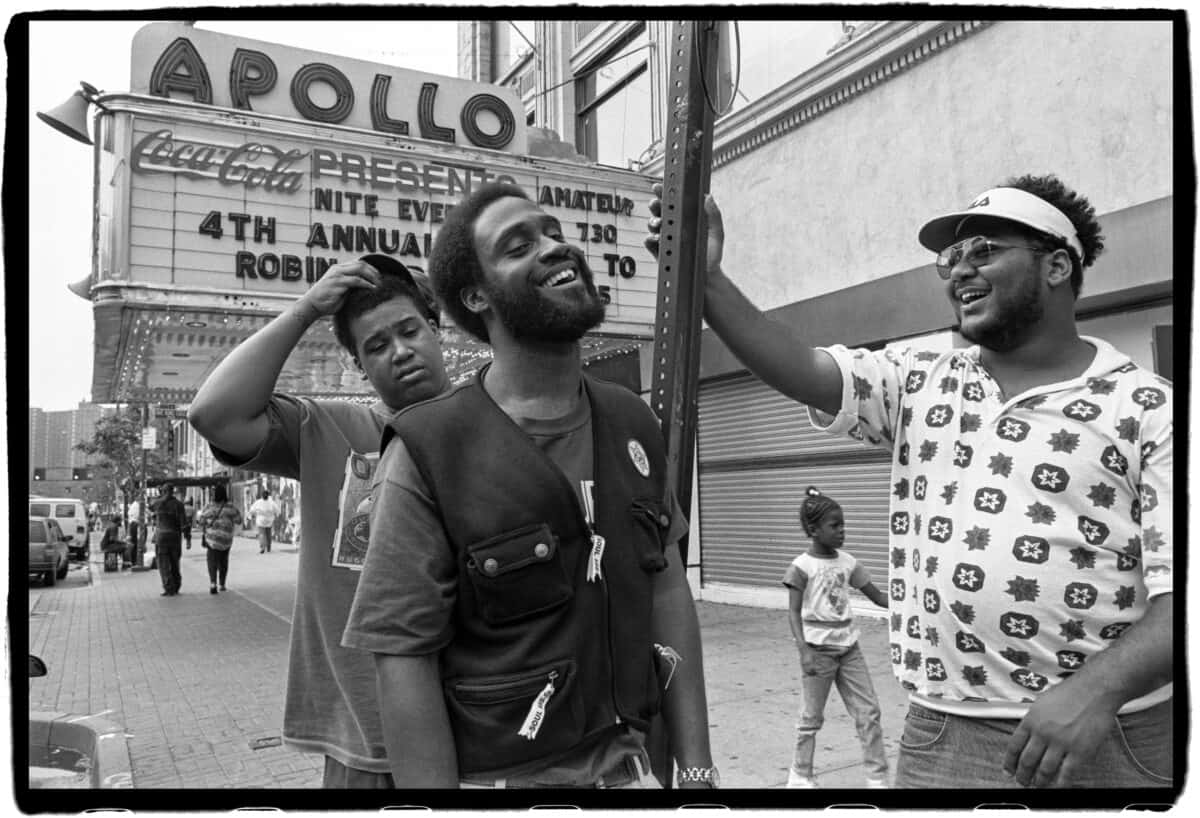

Hip-Hop: Conscious Unconscious, at Fotografiska New York is an exhibition that traces hip-hop’s origins, starting in the Bronx in 1973, as a social movement by and for the local community of African, Latino, and Caribbean Americans—to the worldwide phenomenon it has become 50 years later.

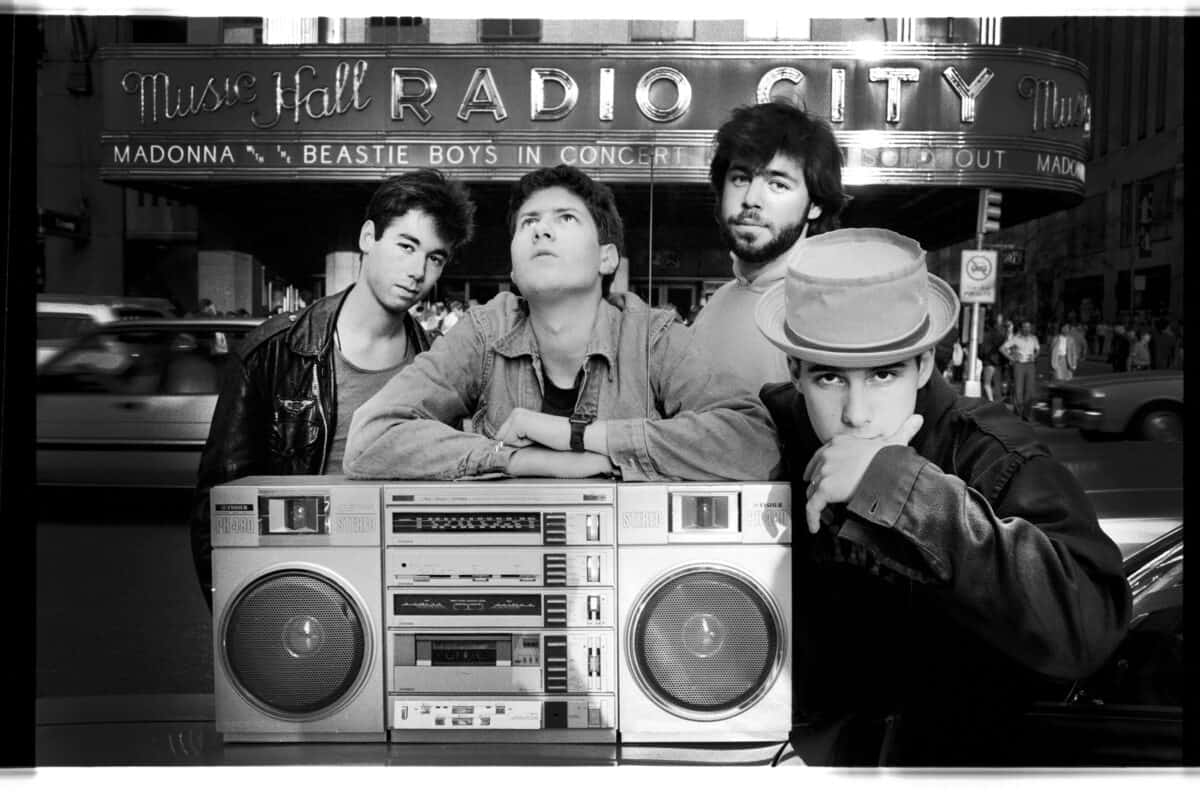

A major exhibition of over 200 photographs, dated 1972 to 2022, traces the rise and proliferation of hip-hop through five decades of work from the trailblazing image-makers who helped codify hip-hop as the most influential pop culture movement of its generation.

Ranging from iconic staples of visual culture (presented with new context) to rare and intimate portraits of hip-hop’s biggest stars, the works on view traverse intersecting themes such as the role of women in hip-hop; hip-hop’s regional and stylistic diversification and rivalries; a humanistic lens into the 1970s-Bronx street gangs whose members contributed to the birth of hip-hop; and the mainstream breakthrough that saw a grassroots movement become a global phenomenon.

Hip Hop: Conscious, Unconscious amplifies the individual creatives involved in the movement while surveying interwoven focus areas such as the set of women who trailblazed amid hip-hop’s male-dominated environment; hip-hop’s regional and stylistic diversification; and the turning point when hip-hop became a billion-dollar industry that continues to mint global household names. The exhibition, created in partnership with Mass Appeal and presented in collaboration with Chase Marriott Bonvoy credit cards, will debut at Fotografiska New York before traveling to several of Fotografiska’s international locations including Fotografiska Stockholm and Fotografiska Berlin.

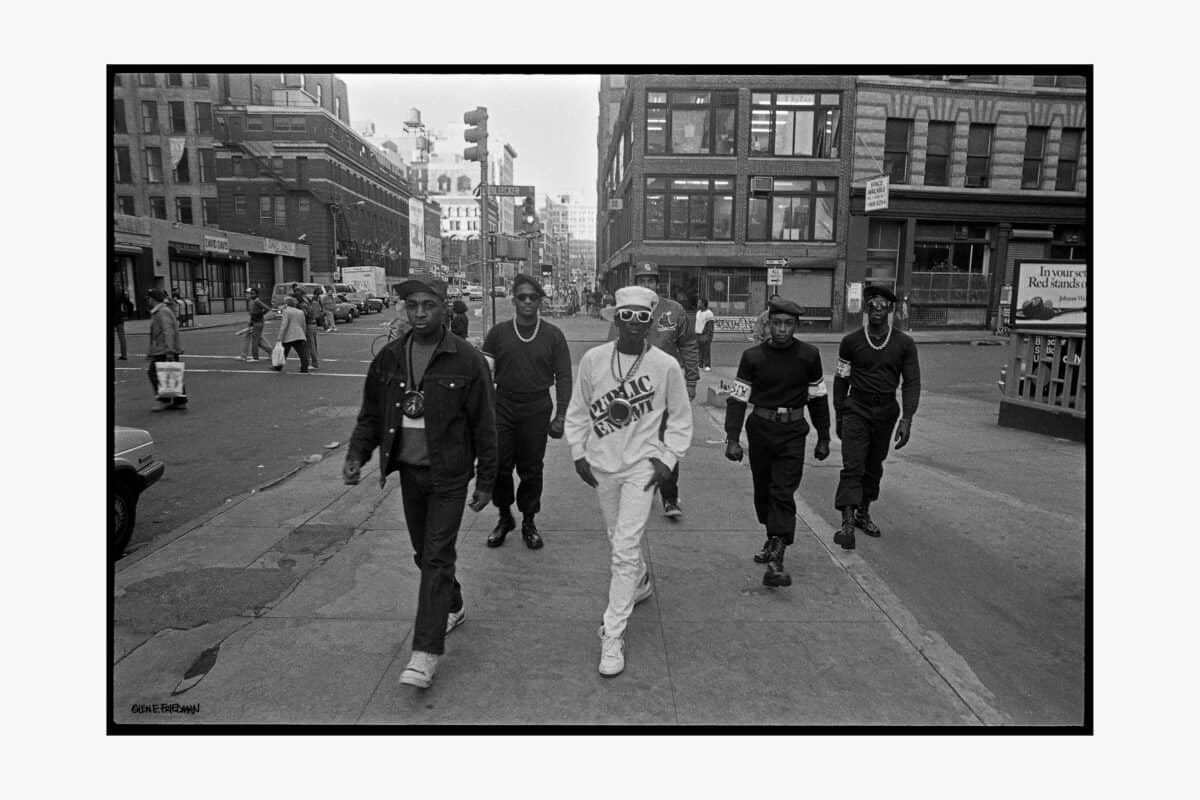

It’s easy to forget that there was a time before hip-hop was an industry and before it made money.

It wasn’t conscious of itself. It was just existing with young people living their lives, dressing as they did, trying to entertain themselves with limited resources and creating an aesthetic that registered among themselves. It wasn’t for the world; it was for a very specific community. Then there was an exponentially paced transition where hip-hop culture became conscious of itself as an incredibly lucrative global export. The exhibition’s lifeblood is the period before hip-hop knew what it was.”

Sacha Jenkins, exhibition co-curator and Chief Creative Officer of Mass Appeal

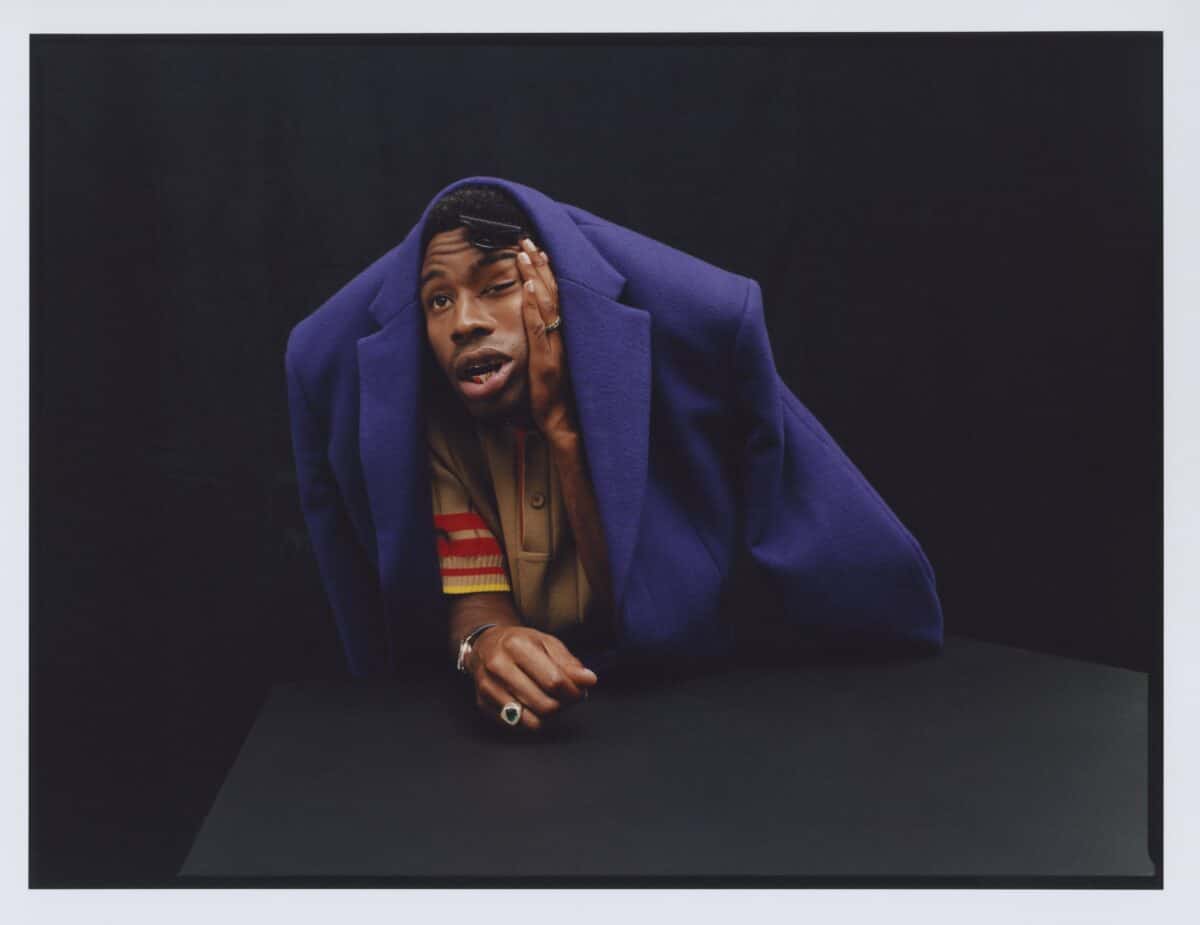

The exhibition brings audiences through five decades of history, culminating in recent imagery of the biggest names working in hip-hop today. The show, which features archival ephemera to augment the contextualization of its photography, is principally laid out by chronology and geography. Focus areas include but are not limited to the early years, East Coast, West Coast, the South, and the newer wave of artists who have emerged since the mid-aughts.

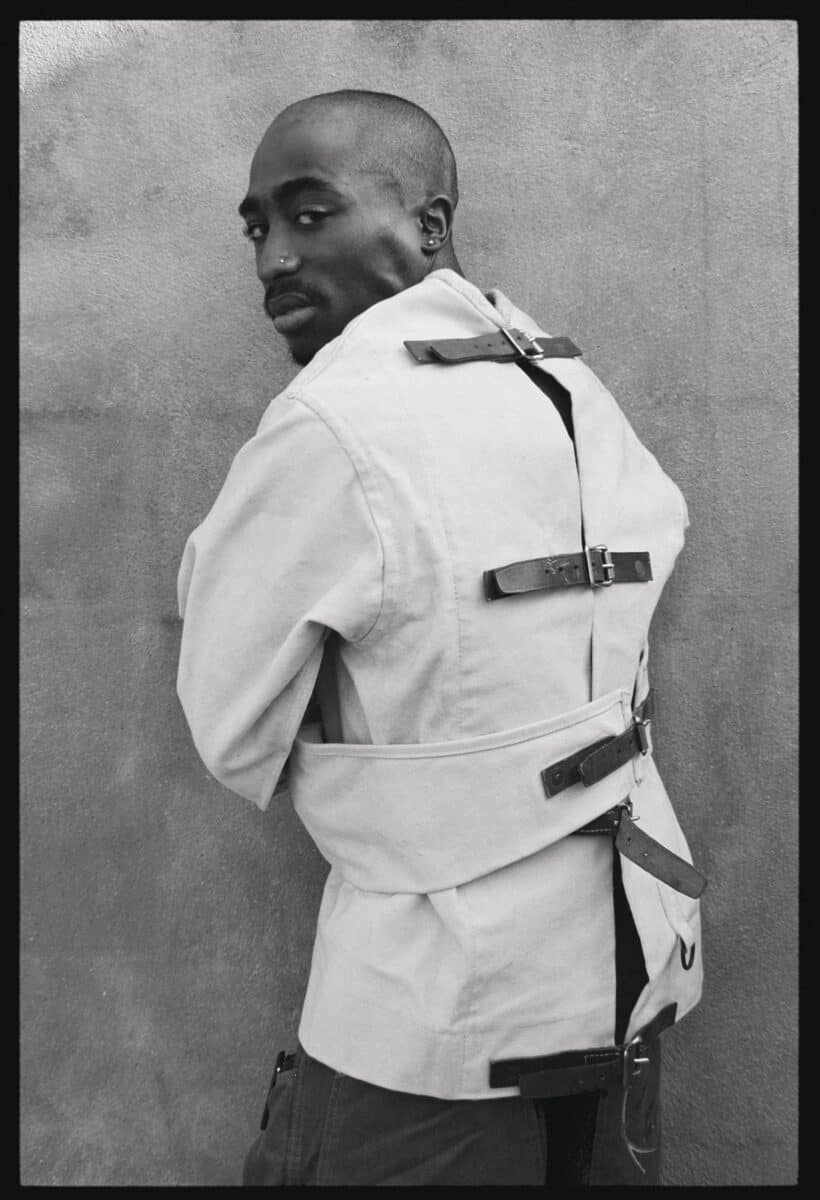

In addition to world-famous photos like Geoffroy de Boismenu’s 1994 portrait of Christopher “Biggie” Wallace staring at the camera with an off-center blunt in his mouth (as well as a rare outtake from the same shoot), the exhibition features compelling early-career snapshots of hip-hop legends, such as Run DMC’s feet under the table at The Fresh Fest press conference (1985); a 20-year-old Mary J. Blige in New

York (1991); Lauryn Hill and Wyclef Jean on an East Harlem rooftop while shooting the music video for Vocab (1993); a candid photo of Tupac and Biggie backstage together at a mutual friend’s concert (1993); Nas in a recording session for his debut studio album Illmatic (1994); The Roots outside of the studio while working on Illadelph Halflife (1996); Talib Kweli and Mos Def enjoying a meal in a Brooklyn diner while taking a break from shooting the album artwork for their critically acclaimed album Mos Def & Talib Kweli are Black Star (1998).

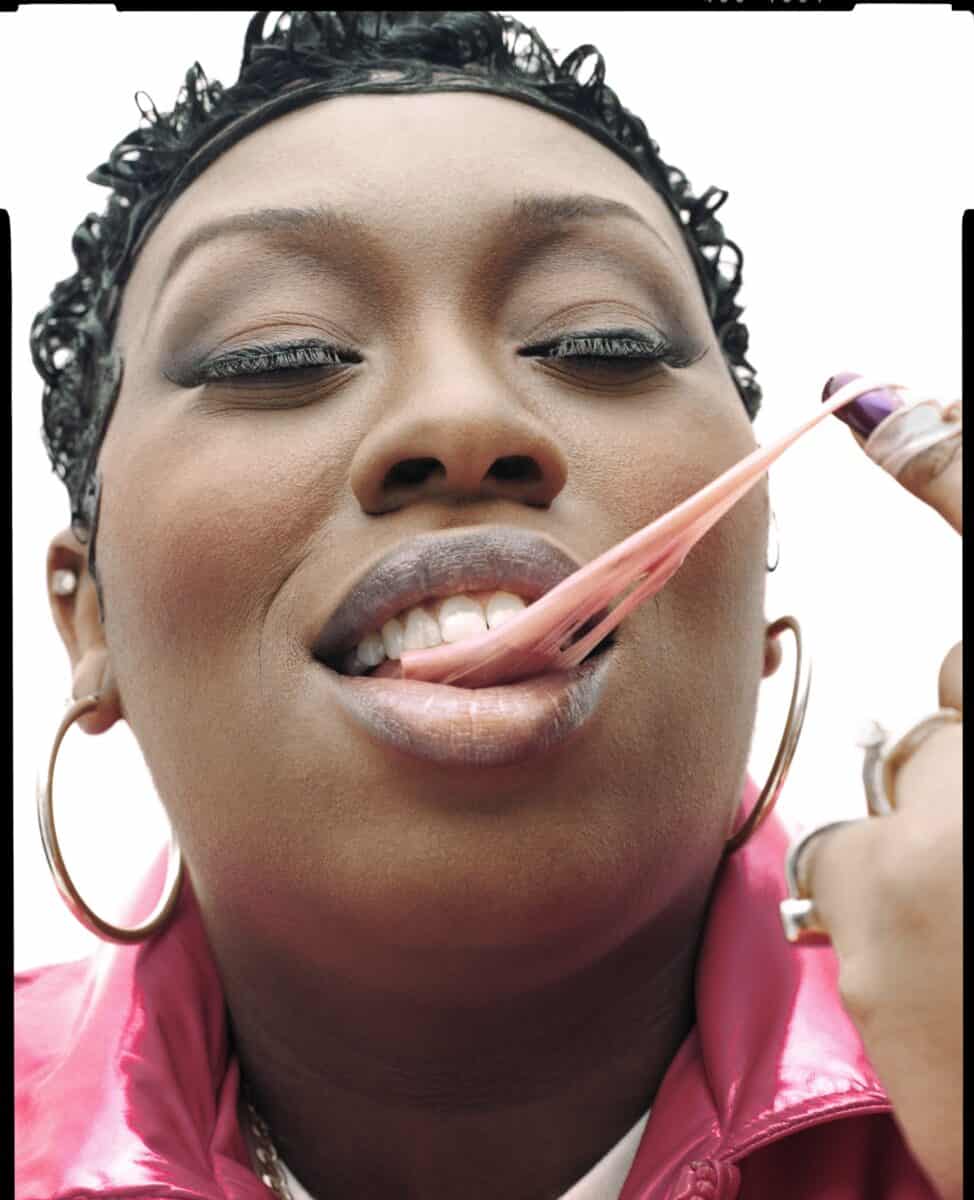

Among other interwoven themes, the exhibition highlights the role of women in hip-hop. More than 20 of the female pioneers who trailblazed in various capacities amid a male-dominated environment are included in the show, such as Cardi B, Eve, Erykah Badu, Faith Evans, Foxy Brown, Lauryn Hill, Lil’ Kim, Mary J. Blige, Megan Thee Stallion, Missy Elliott, Nicki Minaj, Queen Latifah, and Salt N-Pepa.

We made a thoughtful effort to have the presence of women accurately represented, not overtly singling them out in any way.

You’ll turn a corner and there will be a stunning portrait of Eve or a rare and intimate shot of Lil’ Kim that most visitors won’t have seen before. There are far fewer women than men in hip-hop, but the ones that made their mark have an electrifying presence—just like the effect of their portraits interspersed throughout the show.

Sally Berman, exhibition co-curator

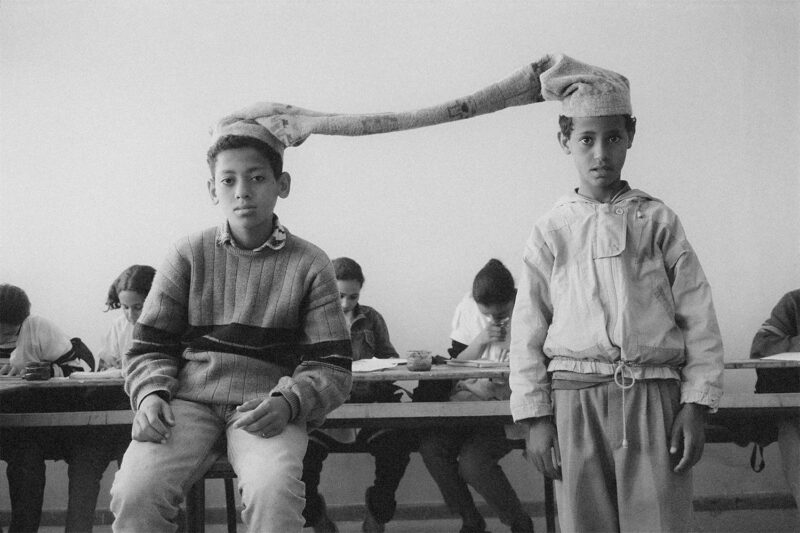

Alongside portraiture of formative names such as DJ Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa, and Grandmaster Flash, documentary images of the larger cultural climate (such as the Savage Skulls street gang, graffiti writers, and block parties) capture the zeitgeist of the Bronx that permeated as the first hip-hop artists innovated the musical style itself. Examples of bodies of work in the show include Jean-Pierre Laffont’s oeuvre of early-1970s Bronx street culture, with a focus on the Savage Skulls; Henry Chalfont’s early 1980s images of Brooklyn, Bronx, Queens, and Downtown Manhattan, with a focus on graffiti writers, breakdancing, block parties, and youthful shenanigans; and Janette Beckman’s late-1980s to early-1990s street-style portraits of hip-hop’s living legends.

The early work in the show is

“More reportage or documentary-style. People were just trying to be local celebrities and superstars at their high school gym or in a park outside. As time goes on and the industry evolves with it, you start to see how things change. You start to see that photo shoots get more fancy. The attire gets fancier; the settings change; you get mainstream signifiers of luxury like private jets and nice cars and iced-out chains and swagger-filled poses. The photographic chronology itself mirrors the evolution of hip-hop, from documentary-style to full on productions.”

For younger hip-hop artists from similar neighborhoods and socioeconomic means as the original superstars, this sequence became the model for success.

Also, key to the show is gang culture, which Jenkins explains

“Was the precursor to hip-hop in terms of creating an identity for yourself,”

especially regarding hip-hop’s core philosophies around self-identification.

When you’re a gang member, you can call yourself ‘Bozo five-oh-five’, right? And that became your identity separate from the identity that your parents gave you. And so hip-hop was the same idea.

You came with a name for yourself as a rapper, you came with a name for yourself as a graffiti artist,

and you took that name and you tried to make something of yourself and something of the name.So that idea of people who typically were not recognized by society, finding a way to make a society for themselves by creating an identity that they can own. Because ownership is really the key with hip hop. Young people were able to create something that they owned. If you were a break dancer and your name was Frosty Freeze and you were really good, you own the Frosty Freeze brand and people respected you for that.”

Tracing the cultural genre’s collective trajectory over five decades, the exhibition spans photography by hip-hop’s earliest documentarians of the 1970s to younger hip-hop photographers who are furthering the proliferation of the genre’s aesthetic.

Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious – 21st May 2023, Curated by Sacha Jenkins & Sally Berman, Fotografiska New York

Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious at Fotografiska New York was created in partnership with Mass Appeal and is co-curated by Sacha Jenkins (Chief Creative Officer, Mass Appeal) and Sally Berman (Visuals Director, Hearst; formerly Director of Photography, Mass Appeal). In-house support comes from Amanda Hajjar (Director of Exhibitions, Fotografiska New York); Meredith Breech (Exhibitions Manager, Fotografiska New York); Johan Vikner (Director of Global Exhibitions, Fotografiska) and Pauline Benthede (VP Global Exhibitions, Fotografiska).