Vito Schnabel Gallery is pleased to present Ai Weiwei: Zodiac, an exhibition focused upon three central groups of work from the artist’s oeuvre, including the triptych Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (2015); twelve wall-based LEGO Zodiac portraits (2018), exhibited for the first time; and the celebrated series Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads: Gold (2010), comprising twelve sculptures in gilded bronze.

Ai Weiwei: Zodiac is the gallery’s first collaboration with the renowned Chinese artist and activist. Engaging Ai Weiwei’s deep admiration for the Duchampian readymade and his longstanding interest in ancient historical artifacts, the works on view in this exhibition raise questions about authenticity and the formation of cultural values, and scrutinize existing power structures. Together, they create tension between past and present, ancient and modern, in order to provoke important conversations about loss and preservation, repatriation and cultural heritage, censorship and surveillance. With Zodiac, Ai Weiwei invites the visitor to join in his exploration of the relationship between an original and a copy, what is “real” and “fake”, and where authorship begins and ends.

In 1995, the artist unveiled Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, one of the most provocative works of his oeuvre up to that point: a series of black-and-white photographs that captured him shattering a precious 2000-year-old ceremonial urn. For the performance documented in these photographs, Ai stood before the camera, staring directly into its lens to confront the viewer’s gaze while the camera shutter clicked. The resulting three images of Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn show the urn in the artist’s hands; the urn falling to the ground; the urn smashing into shards on the floor. Challenging existing value systems through a highly subversive act, this piece was Ai’s response to China’s Cultural Revolution (1966-76), its decade-long desecration of antiquities and relics under Chairman Mao, and the effects of that obliteration via a gesture of both destruction and transformation.

In the exhibition at Vito Schnabel Gallery, visitors will find Ai’s reimagining of this seminal work Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (2015). Created twenty years after Ai’s breakthrough shattering of an ancient urn, the version on view is rendered in LEGO bricks. Arranged in three panels, the LEGO blocks achieve a pixelated black, white and gray-scale effect that approximates digital imagery and surveillance footage – the photography-based idioms familiar to a generation for whom everyday life is mediated by the Internet.

Drawn to them for their accessibility and playful sensibility, Ai has employed LEGO bricks in his artistic practice since 2007. These colorful building blocks are intuitive tools for creative expression and storytelling by children and adults alike. Ai has repeatedly referred to LEGO as a “language”, an analogous form of visual communication that uses patterned, systematic ways of building to express symbols and visual ideas. Its combination of versatility and precision allows the builder to create a specific design– a famous landmark building, for example– from an idea or set of instructions. Its replicability and industrial design as a readymade object, speaks to the influence of his artistic forebears, Warhol and Duchamp. Ai explains: “Lego destroys this idea of an ‘original’, which I like.”

The artist’s longstanding examination of the human condition and critique of authoritarian systems manifests as a poignant statement throughout his work. In the past, Ai has used LEGO to bring attention to human rights violations, acts of censorship, and issues relating to freedom of expression. He has created hundreds of large-scale portraits dedicated to activists and advocates, prisoners of conscience, and victims of crime. In his Zodiac (2018) series, he reinterprets his subject using the bright acid palette of Pop art to render 12 new wall-based LEGO portraits, which have never been publicly exhibited. Each 75 inch square panel will depict one of the 12 animal signs of the Chinese zodiac: the rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog and pig. These will be displayed in the gallery in their cosmological order.

The series, which furthers the important political and cultural narrative that Ai first explored in the twelve bronze sculptures of his well-known work Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads (2010), builds upon his continued interests in digital aesthetics and their centrality to contemporary life. Using a modern material in his artistic vernacular, Ai refashions the historical narrative of these iconic traditional motifs. Chromatically vivid, the bold pixelation of these 12 recognizable creatures creates the visual impact of a graphic video-game. Against a single-hued, saturated background, the animals’ likenesses resolve at a distance, but break down and collapse into a buzzing, fragmented incoherence when observed up close.

Also on view in the exhibition and for the first time ever in Switzerland are Ai’s gilded Zodiac Heads from the series Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads: Bronze and Gold (2010), which has been exhibited at over 45 venues worldwide since 2011. The inspiration for the twelve Chinese zodiac sculptures originates from a water clock fountain that once decorated the famed Yuanming Yuan, an imperial retreat in Beijing dating to the eighteenth century. The pavilions, gardens, and palace at Yuanming Yuan were modeled after French and Baroque styles, designed by European Jesuits for the court of the Qing Dynasty under Emperor Qianlong. During the Second Opium War in 1860, Anglo-French soldiers ransacked the site’s Old Summer Palace and looted the original bronze heads within. In this context, the zodiac is a contentious subject and enduring symbol of China’s fraught history and political unraveling, marked by crushing and humiliating defeat at the hands of Western powers. By excavating and re- interpreting the twelve original animal heads in his work, Ai encourages dialogue about themes of nationalism, cultural heritage, repatriation, and authenticity while introducing humor and wit. His Zodiac Heads function as readymade objects, simultaneously signifying the contradictory powers of history and contemporary pop culture.

Ai Weiwei: ZODIAC, January 27th – February 5th, 2023, Vito Schnabel Gallery, St. Moritz

About the artist

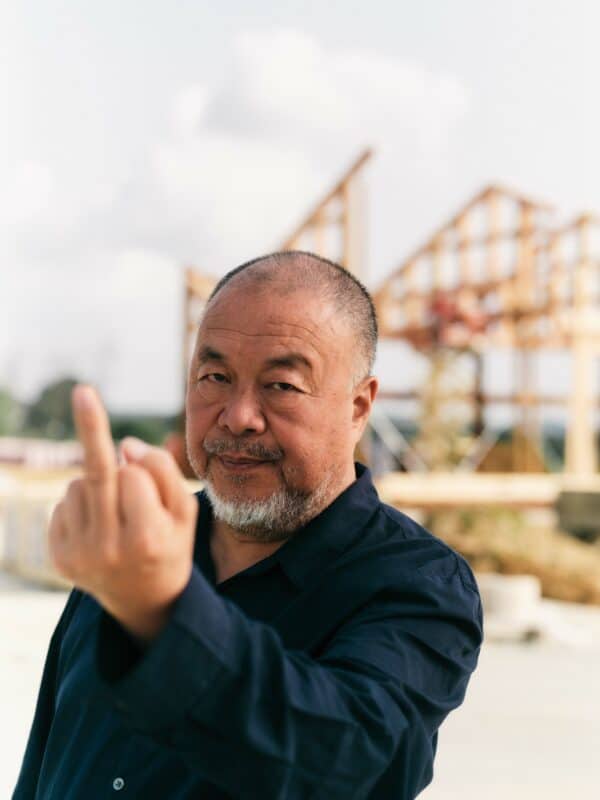

Ai Weiwei was born in 1957 in in Beijing, China. He attended the Beijing Film Academy, and upon moving to New York in the 1980s, continued his studies at the Parsons School of Design. The diversity of his artistic production includes installation, sculpture, photography, performance, documentary filmmaking, architecture, social media and public art projects. A staunch defender of human rights and the freedom of expression, his work taps into the human condition, addressing injustices and truth, advocating for humanity, and providing a critical lens through which to examine humanity’s relationship to nature and the environment and confront systems of economic, political and societal power.

Ai Weiwei is a global citizen, a passionate social activist, creative visionary, and one of the most provocative artists of our time. He grew up as a refugee in his home country. As the son of one of China’s most renowned poets, Ai Qing, his family was exiled to remote provinces along the Northern borders, where they lived and worked in labor camps during China’s Cultural Revolution, before being allowed to return to Beijing in 1976. From 1981 to 1993, Ai Weiwei lived in New York where he absorbed the influences of Andy Warhol, Marcel Duchamp and Jasper Johns. He returned to China in 1993 and helped found the Beijing East Village, a community of experimental, avant-garde artists. In April 2011, he was secretly detained for 81 days by Chinese authorities without charge. In July 2015, the artist’s passport was finally returned. Ai Weiwei emerged as a vocal commentator of China’s authoritarian regime and more and continues to create art that transcends the matrix of Eastern and Western ideas.

Major solo exhibitions include Albertina Modern, Vienna, Austria (2022); Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, UK (2022); Serralves Museum, Porto, Portugal (2021); Cordoaria Nacional, Lisbon, Portugal (2021); Imperial War Museum, London, UK (2020); K20/K21, Düsseldorf, Germany (2019); OCA, São Paulo, Brazil (2018); Corpartes, Santiago, Chile (2018); Mucem, Marseille, France (2018); PROA, Buenos Aires, Argentina (2017); Sakip Sabanci, Museum, Istanbul, Turkey (2017); Public Art Fund, New York, NY, USA (2017); Israel Museum, Jerusalem (2017); Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, Italy (2016); 21er Haus, Vienna, Austria (2016); Helsinki Art Museum, Finland (2016); Royal Academy, London, UK (2015); Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin, Germany (2014); Indianapolis Museum of Art, IN, USA (2013); Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C., USA (2012); Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Taiwan (2011); Tate Modern, London, UK (2010) and Haus der Kunst, Munich, Germany (2009).

In 2022 Ai Weiwei was awarded with the Praemium Imperiale by the Japan Art Association. He won the lifetime achievement award from the Chinese Contemporary Art Awards in 2008 and was made an Honorary Academician at the Royal Academy of Arts, London in 2011. His role as an activist and champion for human rights has been recognized through the Václav Havel Prize for Creative Dissent in 2012 and Amnesty International’s Ambassador of Conscience Award in 2015.