Originally from Ballymena near Belfast, Mark Connolly graduated from the Royal Drawing School in 2017 and is currently based in London. His paintings explore grand themes – good and evil, the theatre of battle, and the arc of the hero – and questions the suitability of such ways of thinking in today’s complex multifaceted world.

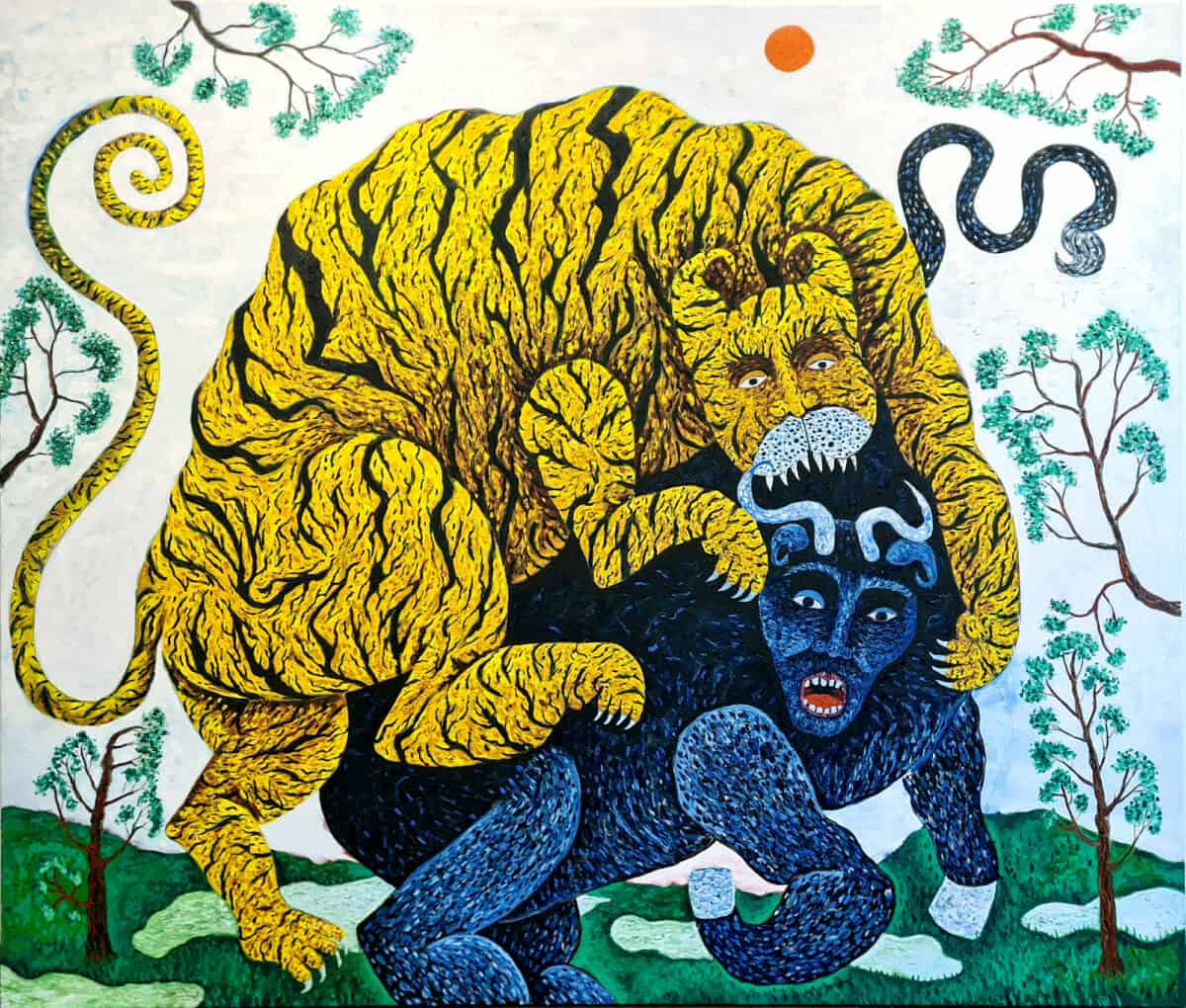

Great battles are the bedrock of Mark’s practice, as shown through his largest canvases. One sees Saint Michael battling Satan as a two-faced devil, the quintessential victory of light over darkness depicted in bright and strident colours. Another depicts a tiger felling a bull, re-interpreting an image of the pitilessness of life that dates back at least 5500 years to the time of the Sumerians. A third depicts a fire breathing chimera, the ancient monster that was the symbol of the unknown horrors that can exist in the imagination. Each gives stark exposure to the conflict of good and bad as it has appeared in visual culture over centuries.

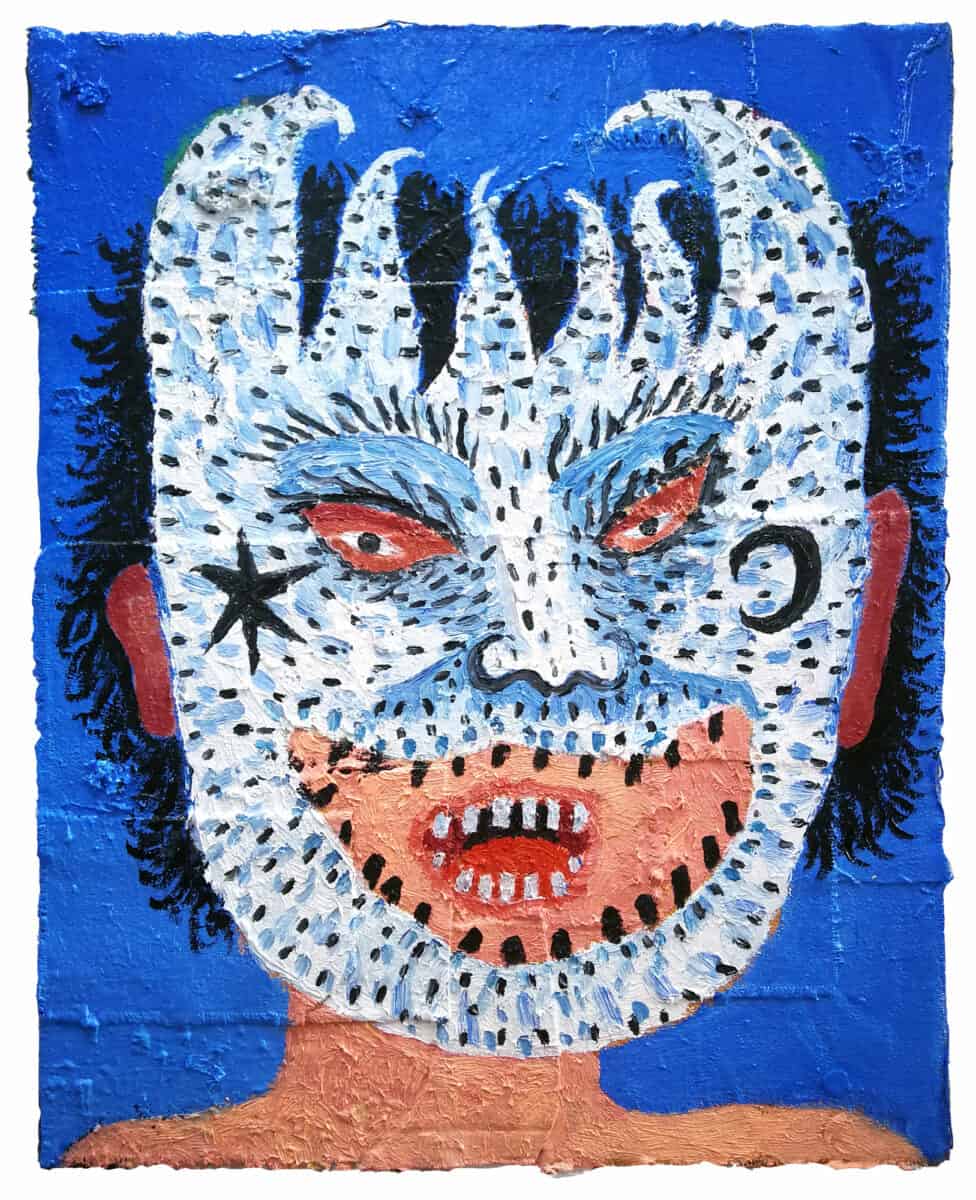

Alongside these works are smaller manifestations of perceived divine interventions within the dualistic mindset. Lightning strikes a lone fisherman; a meteor sears through the sky above an unwitting dinosaur; crocodiles and whales lurk in the depths of tranquil waters. Bringing this closer to home, a portrait of the artist’s brother echoes the narrative of Cain and Abel and the mythical archetype of filial conflict. The theme is then amplified into portraits of contemporary wrestlers such as The Undertaker remembered from weekend afternoon television, as if to underline how the fight of good and evil has been degraded to become a trope for light entertainment.

For all the grandness of his themes, Mark’s distinctive painterly approach emphasizes their fictional quality. His imagery is naive, strikingly so, seemingly rooted in the early-Modern mindset of 1600s Europe, a time of Puritans and religious zealots. Shapes are stark, beasts are mythical, suns are blessed with eyes and the gift of judgement. Such binary narratives, they seem to say, are something of an outmoded fancy. This is not the real world, for reality as we now know it is a far more nuanced and complex beast. And yet, there is a luxuriance in colour and an exuberance of raw drama that suggests the deep-seated appeal that such stories hold for us: as if belief in the eternal fight between good and evil were a human need and not just a desire.

Mark Connolly, an act of god, 12th January to 4th February 2023, James Freeman Gallery

Art opening Thursday 12th January 2023, 6:30-8:30pm.

About the artist

Originally from Ballymena near Belfast, Mark graduated from the Royal Drawing School in 2017 and is currently based in London. His paintings explore grand themes – good and evil, the theatre of battle, and the arc of the hero – and questions the suitability of such ways of thinking in today’s complex multifaceted world. Great battles are the bedrock of Mark’s practice, as shown through his largest canvases. Saint Michael battling Satan as a two faced devil, the quintessential victory of light over darkness. A tiger fells a bull, re-interpreting an image of the pitilessness of life that dates back at least to the time of the Sumerians. Alongside are smaller manifestations of perceived divine interventions. Lightning strikes a lone fisherman; a meteor sears through the sky above an unwitting dinosaur; crocodiles and whales lurk in the depths of tranquil waters.

Portraits of contemporary wrestlers such as The Undertaker remembered from weekend afternoon television underline how the fight of good and evil has been degraded to become a trope for light entertainment. But for all the grandness of his themes, Mark’s distinctive painterly approach emphasizes their fictional quality. His imagery is naive, strikingly so, seemingly rooted in the early-Modern mindset of 1600s Europe, a time of Puritans and religious zealots. Shapes are stark, beasts are mythical, suns are blessed with eyes and the gift of judgement. Such binary narratives, they seem to say, are something of an outmoded fancy. This is not the real world, for reality as we now know it is a far more nuanced and complex beast. And yet, there is a luxuriance in colour and an exuberance of raw drama that suggests the deep-seated appeal that such stories hold for us: as if belief in the eternal fight between good and evil were a human need and not just a desire.