Holly Hendry is stimulated by the inner workings of systems, such as our human biology, instruments used in general medicine, architectural feats, material and matter, as well as undiscovered treasures buried underneath our contemporary layer of the world.

Based in London, Hendry has exhibited sculpture installation art internationally in white cube spaces as well as outdoor public spaces. Hendry incorporates a plethora of materials to accomplish her sculptures. Some materials are utilized to serve their direct purpose, but can also be skillfully manipulated and masked to mimic other textures and convey another feeling.

Similar to an archaeologist, Hendry is inspired by small, hidden obscure objects to construct a larger picture. The networks of materials are fractured, layered, and stacked however they still provide a seamless harmonious interconnection.

The replication and representation of anatomy, earthly minerals, and mechanical elements are highly prevalent within Hendry’s sculptures. A nose, hands, gears, rocks, teeth, water drops, intestines, a tongue, or spinal cords may be woven through, deeply buried, or supporting a structure. The accentuated scale of these dismembered parts infuses their presentation with humor and action.

Fractured and decomposed objects are brought together to create a work that evokes movement as well as a process of transformation and change.

In Fall 2022 Hendry will install her first permanent outdoor public sculpture at Birmingham City University in addition to exhibiting a short-term outdoor public sculpture in Esch-sur-Alzette.

Phillip Edward Spradley: There are a multitude of considerations in processing and executing your sculptures…Personal space, Social space, Geographical space, Positive and Negative space, Two-Dimensional and Three-Dimensional space, just to name a few. With all these components in mind, what are some common practices of how you go about formulating your ideas on a physical plane? Does it come in fragments or in a complete picture?

Holly Hendry: It is never a complete picture – even when the work is finished and installed! My ideas come from a dense aggregate of research (conversations, pictures, stories, materials, movements, architectures, objects etc.) but that starts from a speck of something very immediate or instinctive which everything else is then built on or bounced off of. In a practical sense, you are right to mention lots of variations of space, as space is usually a starting point through spending time in that space, understanding scale and movement and use – trying to suck things into the work or spit bits out. The work usually happens when the research almost overflows; coalescing into one form of an idea which the space has shaped.

P.E.S: There is playfulness in your work which is brought on by exaggerated forms, certain color choices, and the cartoonish depictions. Your work is so relatable as people can see elements of themselves or familiar objects. How do you see humor assisting you to further communicate your ideas?

H.H: Humor is essential and also unavoidable. I’m very serious about humor. I think it is very much tied to a cartoon kind of humor which I have grown up with, where human elements of pain or laughing become elastic and interchangeable. In the cartoon world bodies are freed from real life rules, everyday objects can sometimes move or speak, and death is entirely reversible. Finding humor in an uneasy situation is a way of coping or getting by. So, for me, humor is a method that I can use to address things quite specifically, which relates to the thinking behind my work. For example, the phrase “We laughed to death” ties the human to the lifeless, as if the most humorous act could have the most serious of consequences. Historically, these origins of humour came from new ways of seeing a body that was suddenly being impacted by machines and the comical frustrations of our own awkward bodily limits and the fear or confusion of merging with other objects (nowadays I think we’ve almost merged entirely!).

So I think even the origins of slapstick somehow seem to have infiltrated my approach to making things; machines, movements, animation of the inanimate, bodies, dumb actions and ridiculous appendages, combined with the mundane or ridiculous. I compare the humour within my work to the sensation when you sleep on your arm, cutting off the blood supply, and waking to find that your own limb feels like it has become a rubber replicant of that former body part. It makes you think about the thingness of your own body, detached yet attached.

P.E.S: You are a bit of a rogue chemist and engineer. You explore and integrate various materials to create new forms within a structurally sound object. You are constantly experimenting in new methods of engagement. Your material manipulation and problem solving in the studio align with that of a scientist in a lab and you occasionally work sciencetist. How do you view the relationship between science and art?

H.H: Science and art both start with questions and enquiry, but I think that those paths of enquiry take on rather different forms. I am aware that science has revolutionized art’s means of production – as so many of the materials I use today are products of this – and art can revolutionize scientific thinking – enhancing, expanding or developing an understanding of scientific matters. But to massively generalize, I would say that artists and scientists think in quite different ways, and I think the opportunities to have two different ways of thinking about one specific thing can be quite brilliant, especially when you get the chance to have conversations like this.

I have a scientific approach to research, but practically, a lot of the time in the studio I am trying to not know how to do something too well, or to unpick a traditional method and squeeze or

stretch it into my way of thinking that comes from a hope or an expression…Maybe akin to more of a scientist who’s lost the plot? Sculpture has a unique ability to take up space and be loud or specific without the need for exact words or specific explanation, and I am very invested in the stories that live in materials and their potentials, giving a physical language to things that I can’t quite grasp in any other way. I think there is a science to this which is also wholly unscientific in its approach.

P.E.S: Are there specific archaeological discoveries or biological and technological lifeforms that you are currently investigating?

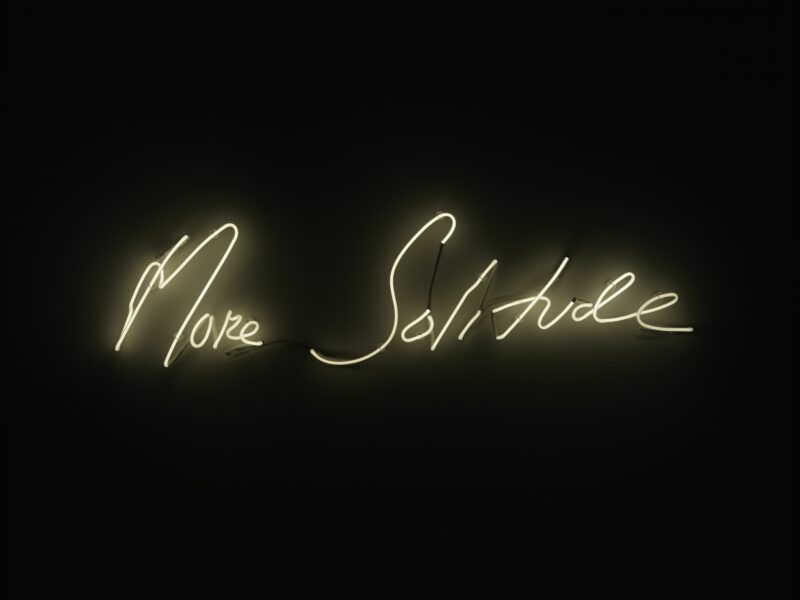

H.H: I am currently thinking a lot about Hungerstones which are inscribed boulders that were laid out in Europe in the 15th – 19th centuries to mark low-water levels at the time. They have been revealing themselves again recently due to the hot weather and draughts. These anthropocentric warning signs sometimes bare grim words of warning reading messages like “if you see me, weep”. I have been struck by such overt emotion and warning from a solid form, and the potential for this as the bearer of signals that could inform decisions we make in the future. It has been making me think about loops and the entanglement between bodies, waters and landscapes which draws on non-Western ways of thinking that challenge the individual as a defined, self-sufficient entity. The body instead is something that is continuously shaped by its environment.

I have also been doing lots of research about the Jacquard loom – a textile weaving mechanism which involves the use of thousands of punch cards laced together to produce fabrics with patterns of almost unlimited size and complexity. The loom (and Jacquard cards which the loom reads) is considered the earliest example of computer software. Its punch card system led to the binary system of ones and zeroes that underpins modern computing and the development of read/write technology central to the history of hard drives. For me, The Jacquard loom links science, computing, materials and images in a haptic and visual way and parallels the tactile element of working things out, which is central to my own practice. I am so interested in the human element of this, as the term “computer” has been in use from the early 17th Century, initially referring to teams of people (often women) who perform calculations; “one who computes”.

P.E.S: You not only use your hands to mold and sculpt your work, but industrial machines, and computers to execute the various components. Ideas are worked out in real time based on the results from mold making. You have to be very practical with your approach as there are calculations and measurements that need to be taken into account. Where do you find malleability in decision-making in your process?

H.H: The precise cuts and calculations usually form the skeleton of the works, and these forms are worked out using computer software, and cut using laser or CNC machines. This forms a structure of sorts, which I can then use as a framework to cast into, add onto, cut up or re-

assemble. The mould-making allows for sloppy moments of material excess where quick colour and material decisions are made, usually by combining other material or textures as aggregates. There are real moments of chaos when I’m pushing a technique to its limits and things are spilling and bursting and stretching, but then the plaster sets and it feels like a fossilization or frozen image of that moment. Often, mould-making implies a copy or repeat process of sorts, but my moulds are mostly cut up or joined (or re-joined), so there is a continual shift in the direction of the work, that is usually within the confines of the scale that the original machine processes implied.

P.E.S: Your works can allude to machines and some even produce movement. This is achieved through forms that indicate directions and suggest movement, then there are mechanics that provide animation. Sculptures can suggest a malfunction or incompatibility or provide action which give a repetition of form. What motions do you tend to pay the most attention to?

H.H: When my works move it is usually only a repeat movement – nothing that feels overly engineered or specifically hi-tech. I am a bit scared of the word kinetic. I guess I see it more as a formal action that is part of the sculpture. So, these movements usually suggest a loop of sorts – a mechanical relentlessness. That repetition becomes really important as it becomes ridiculous – a form of semantic satiation, like when you repeat a word over and over again, it starts to sound different and almost feel like a physical form in your mouth. I think certain speeds and environments affect how these simple actions are interpreted. For example, in 2019 I showed a work at Yorkshire Sculpture Park called Slacker in which a large inlaid silicone band slowly rotated around 12 aluminum rollers. The structure was semi-figurative, with the silicone band depicting innards, detritus and household items like a large plasticky tapestry. I hoped that the slow repetition could reference cycles that relate to the reclined figure, such as digestion when lying down, thought processes/dreaming in sleep, or decomposition in death. The loop and repetition of the motion helped me to consider these ideas of activity and passivity through the work.

More recently, I have been making sculptures that suggest movement rather than display movement, where the works almost try to show their workings out or become graphic notations of themselves. Thinking tools of sorts. I think this aligns to some early animation techniques, so perhaps relates to my constant grapple with image and object, flatness and fullness.

P.E.S: Ideas can be constructed into monumental structures and then they become a part of history. These works interact with the surrounding space which have hidden histories, day to day experiences, meeting points, memories for people. Your work responds to architecture and spaces. How do you consider the relationship between a sculpture, the site, an intended audience, and an unintended audience?

H.H: I always feel very aware, putting work into the public realm, that I have put work in a place where people haven’t necessarily chosen to go to see artwork. Despite the scale of some of my works, I would hope to avoid the idea of monumental in a literal sense always, and some previous works have questioned and critiqued this. I think the everyday in relation to the artwork is something that is much more important; moments, where the work becomes part of a larger construction of a place, is when it means the most.

P.E.S: Planting artwork in a social space can empower artists to be leaders, advocating ideas through art for alternative perspectives that can challenge assumptions, beliefs, and values. Although these sculptures are stationary, they are not fixed objects, they expand outside a frame as shared experiences that contribute toward a sense of community. They can promote community identity, record and celebrate important events, and go on to generate public discourse. Through your investigations what are you wanting to invoke to your audience?

H.H: I don’t believe that the artwork has to be an overly grand gesture, but I hope that the work feels relevant to the site and community it is placed within, that it is able to generate conversation, and to tell (or be part of!) stories that blossom around the building or site

P.E.S: Outdoor sculpture installations differ from those indoors. Natural elements need to be taken into consideration. What do you most enjoy about creating for the outdoors? Are these more challenging in terms of approach?

H.H: Outdoor works are an entirely different set of considerations – from timescales and planning to materials, making, and lifespan of the work, everything seems more stretched out but also more in focus as there are so many variables. All of these added elements mean more conversations, and I really enjoy the collaborative nature of the process that comes with making public sculptures.

I am always interested in risk, but with outdoor works the material risks are within a different context where you consider seasons, moisture, light, wind, temperature… these elements bring material risks to even the most stable of materials. At the moment, I have been thinking a lot about an approach to material re-use in the context of outdoor sculpture – this need for permanence which feels like a battle as nothing is ever permanent in the context of forces of nature.

P.E.S: You are currently working on two outside sculpture installations, one for Esch-sur-Alzette outside of Luxembemberg another for Birmingham City University’s new STEAMhouse project. Can you share where you are in your process and how these may differ from each other and past installations you have taken part of?

H.H: Both of these works are outdoor commissions, and both works reference industry, malfunction, vulnerability and potential, but in very different ways. The work that will be in

Birmingham is my first permanent outdoor work and has really come from so many conversations, communications, workshops and events with people and communities. The work is in the production stage at the moment and I am working with fabricators to produce this. The work will attempt to consider the space between deadness and animation, flatness and fullness, and how we navigate our bodies (as material parts) in contemporary culture.

Excitingly, I have just installed the work in Esch, Luxembourg, so I am finally able to see this in the outdoor context. By contrast to the artwork for Birmingham, I have made this work alone in my studio over the summer, and it is the first time that I have used steam bent wood within my sculptures, which has been a joy and a challenge. I am always very interested in that moment with outdoor artworks, where control is given over to the elements and the public. I am excited to see how it will exist within its environment over time, and how changes in season or weather condition effect the feel and engagement with the work.

Saying that, I am also in the very beginning stages of developing a new series of works for the vitrines on the front of the SCAD Museum of Art which will be installed in early 2024 in Savannah, Georgia. Interestingly, the vitrines sit at street level, so are also public art, despite being protected by a layer of glass, thus creating an entirely different type of public engagement.

Learn more about Holly Hendry by visiting Stephen Freidman Gallery and about the STEAMhouse project.