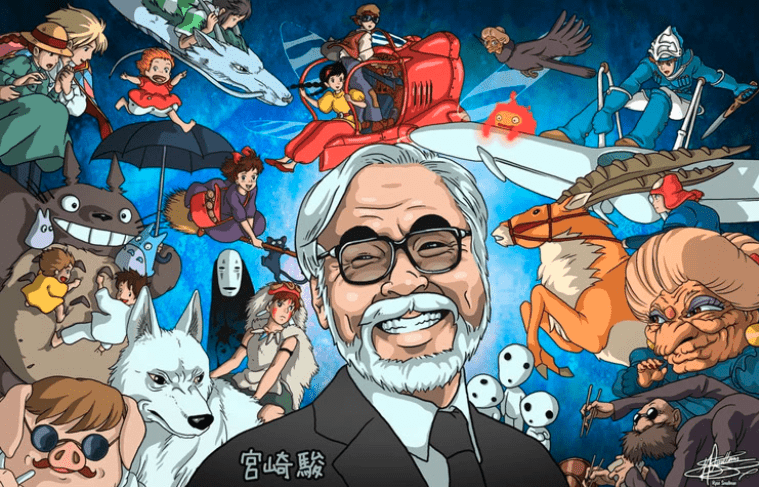

While his latest feature, Kaze Tachinu (The Wind Rises) is due out on our screens early next year, Hayao Miyazaki announced his retirement on September 1st. Then shattering news was announced by the president of Studio Ghibli, Koji Hoshino, during a press conference at the Venice Film Festival.

Now everyone internationally is wondering about the artistic and economic succession of one of the major figures of Japanese cinema.

Who can take over from Hayao Miyazaki? This question has fascinated in Japan and elsewhere, for more than 15 years after the first announcement of his retirement in 1997. Again in 2001, with, each time, a return to business sometime later in very specific circumstances (we will have the opportunity to come back to this). So is this time for real? Even his closest aides don’t know .

An all-powerful director on his land

During the presentation of his new film, Kaguya-hime no Monogatari, Isao Takahata, co-founder of Studio Ghibli, declared:

“He told me that this time, he was very serious but it is likely that it could change. I have known him for so long. Don’t be too surprised if this happens.”

Miyazaki has already started working on a new Samurai Manga set in the Sengoku era. It is almost certain that he will continue to make short films for the Ghibli Museum as well, as he has for years. But let’s admit that the master finally settles down. Why the hell are you looking for a successor now when the guy is still far from having one foot in the grave? It’s that in Japan, Hayao Miyazaki is not just anyone. He is, to date, the only animation director to have achieved such a level of success, on all levels.

Artistically, he has total control over his films, no external constraint can be imposed on him. All of his feature films are huge public successes: he twice topped the all-time Japanese box office with Mononoke Hime (Princess Mononoke) in 1997 and Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi (Spirited Away) in 2001 Chihiro is also still number one in this ranking with more than 23.5 million admissions and profits of over $300 million.

Whether the competition is called Harry Potter, Titanic or Avatar, it always has to back down when Miyazaki releases a film. His latest film, Kaze Tachinu, released in July, has already grossed nearly $120 million and topped the domestic box office in 2013. Miyazaki is also critically recognised with numerous awards, including an Oscar and a Golden Bear in Berlin for Chihiro.

He is the only internationally known Japanese animation director, and no one seems to have the guts to replace him in his own country. Because beyond his successes, Miyazaki is a real workaholic, who has held all possible positions during his career. Starting at the bottom of the ladder as a Toei-style intervalist in the 1960s, he quickly rose to prominence by showing initiative and being proactive. If he had the time, he could take care of all the visual parts of a cartoon on his own, from character creation to animation and storyboarding. Therefore, in his achievements, he is omnipresent and in control of absolutely everything. In short, a genius coupled with a tyrant, often hated by his staff during production.

Its aura is such that, if we confine ourselves to the box office of Japanese animated films, Studio Ghibli is the only one to succeed in placing its achievements at the top of the bill, alongside huge franchises like Pokemon or One. Piece, even when Miyazaki isn’t in charge.

The withdrawal of Miyazaki would therefore create a substantial void and everyone is struggling to find his heirs, capable of sitting on a throne perhaps much too imposing for them. To try and find potential candidates we should obviously start with Studio Ghibli.

Yoshifumi Kondô, the sacrificed youth

And how to evoke this succession without considering the tragic destiny of Yoshifumi Kondô? Born in 1950, this talented key animator quickly rubbed shoulders with Miyazaki and Takahata on various successful 1970s series such as Lupine III, Mirai Shônen Conan and Sherlock Holmes.

The two men eventually convinced him to join Studio Ghibli in 1987. An inveterate hard worker, Kondô knows how to be indispensable and officiates on all the productions of the duo of founders, in turn as animator-chef, chief animator and chara-designer. In 1995, he was entrusted with the direction of his first feature film, Mimi wo Sumaseba (If you listen). Under Miyazaki’s supervision, Kondô delivers a sensitive, personal and inspired film. He manages to combine the imagination and fantasy specific to the Studio with a more contemporary setting, rooted in reality.

The two patriarchs are convinced of this: they hold there their successor, called to take over when they retire from the world of animation. With him, the Ghibli institution would be in good hands. Kondô becomes chief animator again on Mononoke Hime in 1997 and Miyazaki, confident, announces his (first) retirement after the historic success of his last film. But everything collapses a few months later. On January 21, 1998, Yoshifumi Kondô succumbed to an aneurysm, probably due to overwork. Hayao “Napoleon” Miyazaki has just lost his eaglet. Devastated by this disappearance, the master cancels his retirement and returns to business, swearing to release the pressure and work less hard.

From this moment, Miyazaki and Takahata, accompanied by the emblematic producer of the Studio, Toshio Suzuki, begin to actively seek directors likely to replace them periodically.

Gôro, the son that Miyazaki refused to be seen by his side

Then lands, through a back door, Gorô Miyazaki, son of the master and legal heir, if not perhaps legitimate. And their relationship is nothing short of a fairy tale. Hayao Miyazaki is an absent father, obsessed with his work, and his growing success is a real weight on the shoulders of his offspring. Attracted in his youth by a career in animation, he finally decided to study landscape design in order to avoid comparison with his illustrious parent.

But in 1998, everything changed. While Miyazaki senior was working on Spirited Away, the Studio wanted to create a museum in Mitaka, in the suburbs of Tokyo, in order to offer exhibitions, short films… and to bring money into the coffers. Suzuki presented the project to Gorô who would supervise the construction of the building and the layout of the garden. He even became the museum’s director of operations.

In the years that followed, the producer asked him to participate in meetings on the adaptation, then at a standstill, of a novel by Ursula K. Le Guin, The Sorcerer of Earthsea. Fan of the book, Gorô accepts and begins to propose ideas and sketches. Toshio Suzuki sniffs out a good deal and offers him the direction of the film which will later be called Gedo Senki (Tales from Earthsea). The son can finally embrace his childhood dream. To the chagrin of his father who fiercely opposes this idea, judging Gorô too immature and inexperienced to carry out such an enterprise. Enormous tensions are created and the two parents will no longer speak to each other for the duration of the production, which is approximately 9 months.

During the internal preview of the film in 2006, Hayao Miyazaki is present, against all odds. But it is to better leave the room after an hour of projection. And the father’s judgment on his son’s feature film is uncompromising: “I had the impression that I had already been sitting for 3 hours… […] I find that he worked really seriously and that’s all. No other things to add. Personally, I think it was a job that was not worth doing. “He will even split a letter to Goro writing to him” You were worthy of yourself “…

The film is a hit with the public but the critics are harsh. Gorô is put away in the closet for almost 4 years. In 2010, after several rejected concepts, he ended up recovering an old project from his father, Kokuriko-zaka Kara (The Hill of Poppies), based on the eponymous manga, published in the 1980s. Suzuki plays the mediator and asks Hayao Miyazaki to write the screenplay. The collaboration is stormy: if the master seems to accept little by little that his son becomes a director, their vision of the film diverges.

Completed in 2011 in an uncertain economic and social context, due in particular to the natural and nuclear disasters of March, La Coline aux Coquelicots is a great success. Gorô’s work is certainly academic but does not lack charm. The son settles permanently in the Ghibli stable. His third film would already be on the shelves for 2014-15. But difficult for him to get rid of his image of boosted daddy’s boy and above all, difficult to think that Hayao Miyazaki considers him as his successor.

“Maro” Yonebayashi, the Studio Ghibli baby bottle class at the helm

Because the master has already set his sights on someone else, in the person of Hiromasa Yonebayashi. A pure product of Studio Ghibli, the young man, nicknamed “Maro” by his peers, started out as an intervalist on Mononoke-hime before gradually rising in rank.

tit. A talented animator, he revealed himself completely during the production of Gake no Ue no Ponyo (Ponyo on the Cliff) where we owe him the famous and superb scene of the waves.

Enthusiastic, Miyazaki entrusts him with the direction of Kari-gurashi no Arietti (Arrietty, The Little World of Pilferers). Yonebayashi becomes the youngest director in the Studio’s history and impresses his collaborators during production. His sense of work and his abnegation even recall the attitude of Miyazaki, who completely supports him in his development, unlike his son.

A contrast that will burst during the preview of Arrietty where the master would have stood up, shouting “Good job, Maro! “, later stating that he was “the first director born and raised in Studio Ghibli”. Like Gorô, Yonebayashi is already working on his next feature film, scheduled for summer 2014. According to Japon Samouraï website, it would be the sequel to Porco Rosso.

We can nevertheless legitimately wonder if these two colts really have the stature to occupy the place left vacant by Miyazaki. They will certainly benefit from the aura of Studio Ghibli and its founders, but they will never acquire the same notoriety or the same success. Their films are solid but lack a real creative edge.

On the other hand, pushed by Suzuki, they will blend perfectly into the Ghibli mould, ensure its durability and replenish the coffers emptied by the original but often unprofitable projects of Isao Takahata (his last film, in production for 8 years, would have cost nearly $50 million!). It is also not excluded that a new director emerges, to everyone’s surprise, from the Studio teams, like Yonebayashi. One thing is certain: the departure of Miyazaki should not create a breaking point within the Ghibli institution for two or three years, the schedule of releases having already been recorded. It will then be time to question ourselves again or even to speculate on a possible return of the master to business for an ultimate masterpiece.

Makoto Shinkai, fake Miyazaki but true jewel of independent animation

But an aspirant to the throne can also tumble from the borders of the kingdom. What about the other directors outside Studio Ghibli? Here again, many names were considered and then swept away. One of those who has come back regularly in recent years is that of Makoto Shinkai, especially since his film Hoshi o Ou Kodomo, (Journey to Agartha), released in 2011.

Pillage in good standing of the Ghibli universe, the feature film will seek its scriptwriting and graphic aspirations in turn at Nausicaä, Laputa, Chihiro or even Mononoke. The result is a kind of sub-Miyazaki, not necessarily indigestible but singularly lacking in personality. And yet, Shinkai does not lack it and is a somewhat special figure in current Japanese animation.

Working for a video game company in the 1990s, the young man made an entire 5-minute short film in black and white, Kanojo to Kanojo no Neko (She and Her Cat). By selling it at conventions on burned CDs, he caught the attention of a publishing company, which offered to finance his next project. This time, Shinkai quit his job and spent 7 months designing Hoshi no Koe (Voices of a Distant Star) on his computer. This 25-minute OAV meets with unexpected success. The public and the critics are impressed by the titanic work done by a single person, who is moreover totally self-taught.

Shinkai demonstrates that it is possible to produce a quality anime with an extremely small staff and at low cost thanks to new digital creation tools. Follower of full digital, Makoto Shinkai becomes, somewhat in spite of himself, the standard bearer of a new independent animation, on the fringes of traditional studios, paving the way for some pearls like Eve no Jikan (Time of Eve). New successes of esteem followed for him with Kumo no Mukô, Yakusoku no Basho (The Tower beyond the Clouds) and Byôsoku Go Senchimêtoru (5 cm per Second). His style becomes extremely recognizable: very soft visuals, decors reworked from photos and ultra pronounced light effects. Shinkai wishes to sublimate reality, to make it even more beautiful than it is. His favorite themes: relationships, often romantic, between people and the idea of a lack of emotion.

Doomed to niche success?

The result is productions that are full of peepers, often hit just at the level of the emotions provoked, but remain very conventional. Shinkai is not intended to become the new Miyazaki, contrary to what some critics have suggested, because it is not aimed at the same audience at all. His approach is very different from the universality sought by Studio Ghibli feature films. Above all, he wants to make films for people usually uninterested in animation and who do not feel involved in it.

As a result, he is condemned to stay in a certain niche and the situation seems to suit him perfectly, as he repeats at leisure being overestimated and that within a few years, another director could have stood in the same place as him.

How then to explain the Agartha incident which contrasts with the rest of his filmography? Armed with a much larger budget than on his previous achievements, we can think that Shinkai feared that he would never have such a sum at his disposal again. Hence a sometimes coarse accumulation of ideas in a more family adventure, bringing together multiple influences, which sometimes do not resemble him. Since then, the young man has returned to formats and stories that suit him much more with Kotonoha no Niwa (The Garden of Words), released in 2013.

But even if Shinkai is not the long-awaited successor and if his aura will never exceed certain circles of very particular amateurs, he still has a significant margin of progress. His style and his ability to work quickly allow him to experiment a lot, especially in the field of communication with the production of several high-end animated advertisements.

Mamoru Hosoda: the aborted experience at Ghibli

And just as everyone is desperate to find someone who can extract Excalibur from the rock, along comes Mamoru Hosoda. Born in 1967, he started his career as an animator at Toei after being rejected… from the Studio Ghibli training institute. Intervallist, key animator, episode director, the man touches all positions.

Hosoda even works under a pseudonym for other studios, trying his hand at scripting and storyboarding, notably on Utena in 1997. The Toei decides to entrust him with the production of the first Digimon film, Digimon Adventure, a 20-minute opus released in cinemas in 1999 to promote the launch of the TV series on the air the next day. Far from the ultra-calibrated commercial product that one might have expected, the film is surprising. Hosoda installs a slow narration, which takes the time to distill a paradoxical atmosphere (very young children find themselves at the controls of ever more powerful and frightening monsters against the backdrop of Ravel’s Bolero). The urban settings are beautiful, the animation in tune and the staging, perfectly adapted to the cinema, demonstrates all the latent potential of Hosoda.

Rebelote the following year with the production of the second film in the franchise: Digimon, Bokura no War Game! (Digimon, Our War Game!). In 40 minutes, the medium-length film foreshadows everything that will later make the strength of the director. First of all, an eminently recognizable graphic style. Hosoda is a follower of superflat, an artistic movement popularized among others by Takashi Murakami (the latter will also ask Hosoda to collaborate on a stunning advertisement for Louis Vuitton, Superflat Monogram). This is characterized by solid colors of a single tone, few reflections and shadows on the characters, making it possible to make complex movements very simple.

The director also offers, in parallel, a draft of a floating virtual universe, teeming with details and ultra-colourful, which we will find sublimated years later in Summer Wars, of which the film Digimon is a sort of preparatory canvas both the Similarities between the two works are obvious. In terms of themes, Hosoda constantly plays on the duality of the worlds (real and virtual) and the symbol of play when you are a child. In an interview given in 2010, the director explains: “I want to draw the real world, basically. And to give it more importance, I oppose it with another world. Also, for the characters, returning from a parallel world helps them enjoy their own world more. »

Thanks to this second opus, Hosoda ends up catching the eye of Toshio Suzukiu and Hayao Miyazaki. The latter has just retired for the second time after Chihiro’s consecration, and Studio Ghibli is looking for a director for its next project: Hauru no Ugoku Shiro (Howl’s Moving Castle).

Miyazaki seems to recognize himself in Hosoda because of their somewhat similar career as jack-of-all-trades in animation. But what should have been a superb opportunity for the young director turns into a poisoned gift.

A few months after being hired, Hosoda was forced to leave the ship, officially for artistic disputes. Hosoda would have suffered many clashes with the production team, reluctant to follow his ideas and his storyboard, too far from the canons of the Studio. Years later, he will have this terrible maxim: “Studio Ghibli is a structure that was created essentially to allow Mr. Miyazaki to produce his works and unfortunately not to create other things. »

Miyazaki will also be forced to return to the helm in disaster to complete the production of the feature film but will refuse to participate in the promotion of the film, aware of the wobbly result delivered. For his part, Mamoru Hosoda thinks he has just missed the chance of his life…

The start of a new dynasty?

Paradoxically, this failure at Ghibli will become a real starting point for Hosoda. Rehired by Toei (a rare occurrence), he is in charge of the 6th One Piece film: Baron Omatsuri and the Island of Secrets. Here again, the young director brings his artistic and thematic touch to a franchise universe. He enjoys total freedom and asks outside animators to completely transform the usual chara-design of the franchise to adapt it to his graphic style of superflat. The fights, central elements in normal times, are replaced by games more crazy than each other but just as dangerous. Above all, through his scenario, Hosoda settles his accounts. A metaphor for his failed stint at Ghibli, the story sees the group of heroes gradually disintegrate, blaming their captain for his bad decisions and leaving him alone to face the ultimate test. Communication, friendship and mutual aid will be the key words that will finally allow the band to get out of it in extremis, in a beautiful artistic Oedipus complex.

When the film is released, the anger of fans is unprecedented, outraged by what Hosoda has done to their franchise. But this allowed him to get noticed by the Madhouse studio, which produced Toki wo Kakeru Shôjo (La Traversée du temps) in 2006 and Summer Wars in 2009, two feature films which established Mamoru Hosoda as an important director, always at the center of his preoccupations with parallel universes and the notion of passing time.

In 2012, he left Madhouse, founded his own studio (Studio Chizu), like Miyazaki in his time, and released Ôkami Kodomo no Ame to Yuki (The Wolf Children), a moving humanist fable about a courageous mother, having to raise children alone. lycanthropes, with all the disadvantages that implies. With more than 50 million dollars in box office receipts and 4 million admissions in Japan, the feature film is positioned in the top 20 of the biggest animation successes, a very closed circle hitherto reserved for Ghibli and to franchise films. Above all, it tends towards the universality sought by the works of Miyazaki. Hosoda becomes known for his name as a director, after only 3 personal films and proves capable of attracting spectators thanks to original projects, esteemed by the public and critics. It would not be surprising that Hosoda wins, in the years to come, some prestigious international awards like Miyazaki.

He also begins to follow the operation of Studio Ghibli in terms of merchandising in order to guarantee him a certain financial independence. Hosoda even revealed at the world premiere of Les Enfants Loups in Paris last year that he was considering inviting new directors to his studio. If this doesn’t remind you of someone…

Paradoxically, today, Miyazaki’s most credible spiritual and economic heir is someone who has failed within his own structure. Perhaps a blessing in disguise because the freedom that Hosoda now has is beyond measure. His very personal films would probably never have seen the light of day in Studio Ghibli. Mamoru Hosoda has everything to recover the family niche that Ghibli claims, provided of course that he finds funding and sponsors in line with his ambitions. Which shouldn’t be a big problem given the progress of the guy and the income he is able to generate. Besides, Toshio Suzuki would always keep an eye on him…

From there to imagining a fanfare return of the fallen pretender within Ghibli to give him a new life, there is a step that we will not take. If it seems obvious that Hayao Miyazaki could not be replaced (or even perhaps equaled) in the panorama of Japanese animation, Mamoru Hosoda has all the cards in hand to build a nice throne, which will only look like to him.