This autumn a major exhibition at the British Museum will mark one of the most important moments in our understanding of ancient history: the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs. Hieroglyphs: unlocking ancient Egypt will explore the inscriptions and objects that helped scholars unlock one of the world’s oldest civilisations, exactly 200 years since this pivotal moment.

The decipherment of hieroglyphs marked the turning point in a study that continues today to reveal secrets of the past. The field of Egyptology is as active as ever in providing access to the ancient world. Building on 200 years of continuous work by scholars around the globe, the exhibition celebrates new research and shows how Egyptologists continue to shape our dialogue with the past.

Ilona Regulski, Curator of Egyptian Written Culture at the British Museum

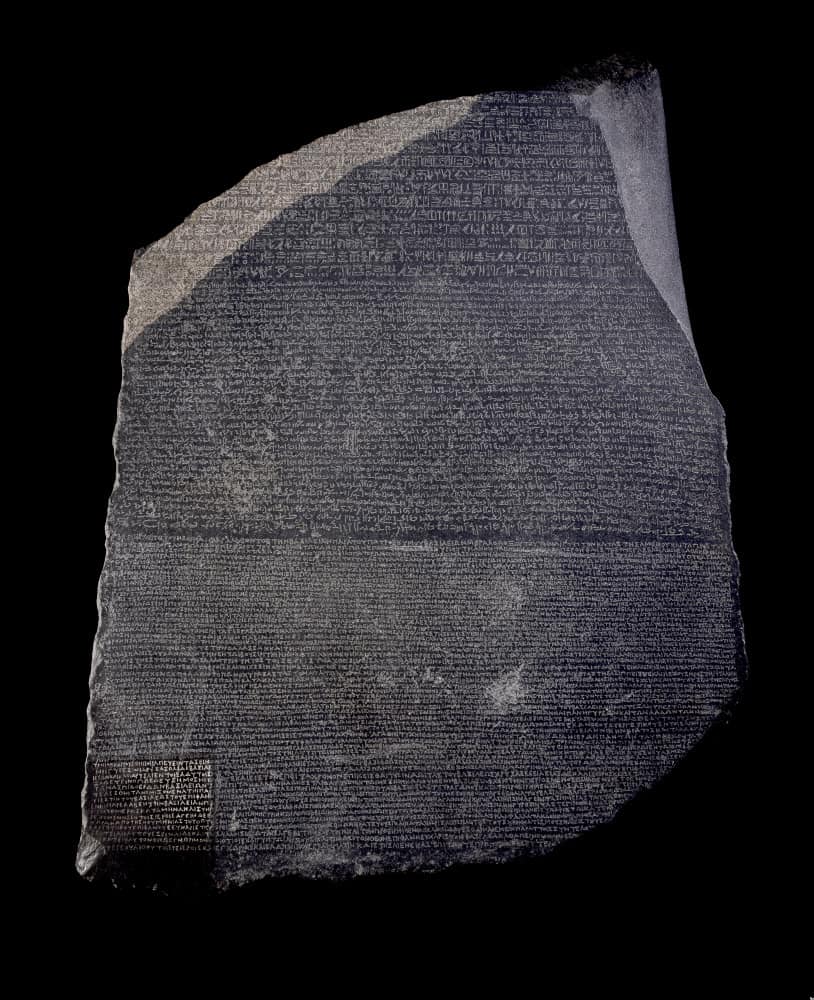

At the exhibition’s heart will be the Rosetta Stone, amongst the world’s most famous ancient objects and one of the British Museum’s most popular exhibits. Before hieroglyphs could be deciphered, life in ancient Egypt had been a mystery for centuries with only tantalising glimpses into this forgotten world. The discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799, with its decree written in hieroglyphs, demotic and the known language of ancient Greek, provided the key to decoding hieroglyphs in 1822; a breakthrough expanding the modern world’s knowledge of Egypt’s history by some 3,000 years.

This immersive exhibition will bring together over 240 objects, including loans from national and international collections, many of which will be shown for the first time. It will chart the race to decipherment, from initial efforts by medieval Arab travellers and Renaissance scholars to more focussed progress by French scholar Jean-François Champollion (1790 – 1832) and England’s Thomas Young (1773 – 1829). The Rosetta Stone will be viewed alongside the very inscriptions that Champollion and other scholars studied in their quest to understand the ancient past. The exhibition will also feature stunning objects that highlight the impact of that breakthrough.

Star objects include ‘the Enchanted Basin’, a large black granite sarcophagus from about 600 BCE, covered with hieroglyphs and images of gods. The hieroglyphs were believed to have magical powers and that bathing in the basin could offer relief from the torments of love. The reused ritual bath was discovered near a mosque in Cairo, in an area still known as al-Hawd al-Marsud – ‘the enchanted basin’. It has since been identified as the sarcophagus of Hapmen, a nobleman of the 26th Dynasty.

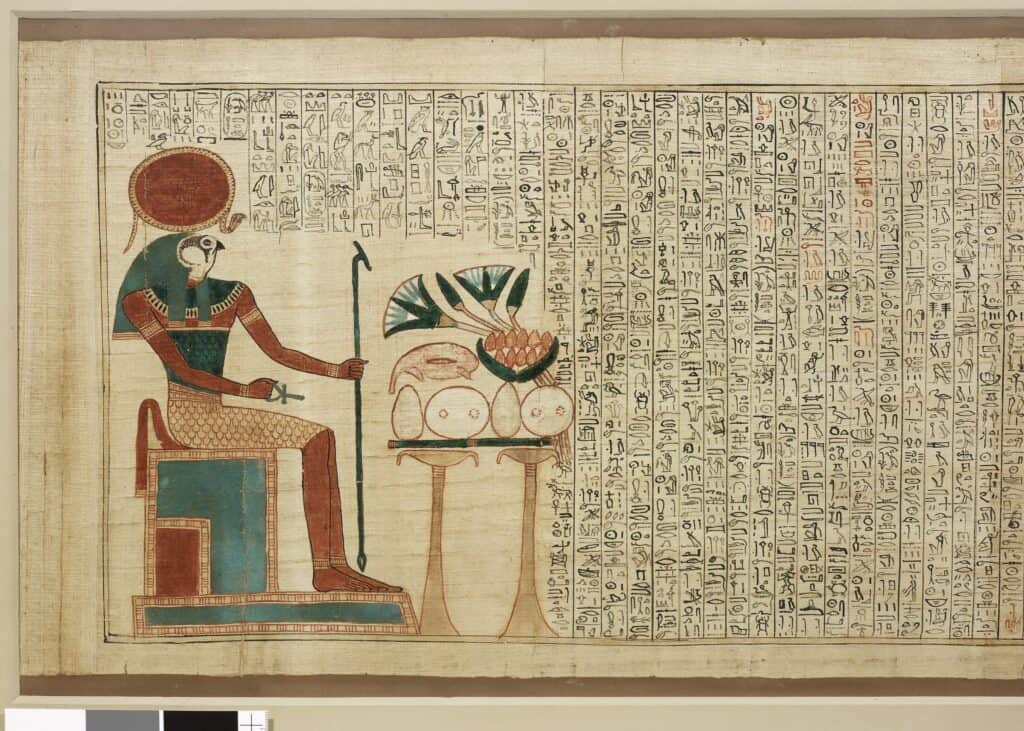

Rarely on public display, the richly illustrated Book of the Dead papyrus of Queen Nedjmet is over 3,000 years old and more than four metres long. A recitation of the texts demonstrates the power of the spoken word, with ritual spells there to be pronounced. The papyrus will feature alongside a set of four canopic vessels that preserved the organs of the deceased. These were dispersed over French and British collections after discovery, and this is the first time this set of jars has been reunited since the mid-1700s.

Among the exceptional loans to the exhibition is the mummy bandage of Aberuait from the Musée du Louvre, Paris, that has never been shown in the UK. It was a souvenir from one of the earliest ‘mummy unwrapping events’ in the 1600s where attendees received a piece of the linen, preferably inscribed with hieroglyphs. The exhibition will also bring together personal notes by Champollion from the Bibliothèque nationale de France, and Young from the British Library. A 3,000-year-old measuring rod from the Museo Egizio in Turin was an essential clue for Champollion to unravel Egyptian mathematics, discovering that the Egyptians used units inspired by the human body.

The striking cartonnage and mummy of the lady Baketenhor, on loan from the Natural History Society of Northumbria, was studied by Champollion in the 1820s. In correspondence with colleagues in Newcastle, Champollion correctly identified the inscription on the mummy cover as a prayer addressed to several deities for the soul of the deceased only a few years after he cracked the hieroglyphic writing system. Baketenhor lived to about 25–30 years of age, sometime between 945 and 715 BCE.

From love poetry and international treaties, to shopping lists and tax returns, the exhibition reveals fascinating stories of life in ancient Egypt. As well as an unshakeable belief in the power of the pharaohs and the promise of the afterlife, ancient Egyptians enjoyed good food, writing letters and making jokes.

Many people in ancient Egypt could not read or write so language was enjoyed through readings, recitations and performances. The exhibition will include digital media and audio to bring the language to life alongside the objects on display. As part of the interpretation, the British Museum has worked with Egyptian colleagues and citizens from Rashid (modern-day Rosetta), with their voices featured throughout the exhibition.

Hieroglyphs: unlocking ancient Egypt marks 200 years since the remarkable breakthrough to decipher a long-lost language. For the first time in millennia the ancient Egyptians could speak directly to us. By breaking the code, our understanding of this incredible civilisation has given us an unprecedented window onto the people of the past and their way of life.

I would like to express my gratitude to our long-term exhibition partner bp. Without their support, the British Museum would not be able to present such exhibitions, allowing visitors to discover the art, culture and language of ancient Egypt through the eyes of the pioneering scholars who unlocked those ancient secrets.

Hartwig Fischer, Director of the British Museum,