I must admit that before I visited the Kawanabe Kyosai exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, I wasn’t familiar with his work, and expected to see something in the vein of the revered Japanese artist Hokusai. Kyosai is considered to be a close successor of Hokusai, however, the exhibition felt more like looking at the work of an illustrator and satirist than a fine artist.

Kawanabe Kyosai (1831-1889) was among Japan’s most important master painters and during his lifetime gained a reputation for his independent spirit and witty art. The legacy of his style endures to this day in artforms of manga and tattoo art. Kyosai was overlooked for some time in favour of his artistic predecessors Hokusai and Hiroshige, until his art was rediscovered and became celebrated for creating a bridge between popular Japanese culture and traditional Japanese art.

The Royal Academy is presenting a curated selection of Kyosai’s art from the collection of art dealer Israel Goldman, in Kyosai’s first UK exhibition in almost 3 decades. Kyosai studied art under the ukiyo-e artist Kuniyoshi at the Tokugawa governments appointed painting school and went on to fuse academic training in traditional Japanese art with imagery inspired by satirical and comic-book images, thus creating his own unique style.

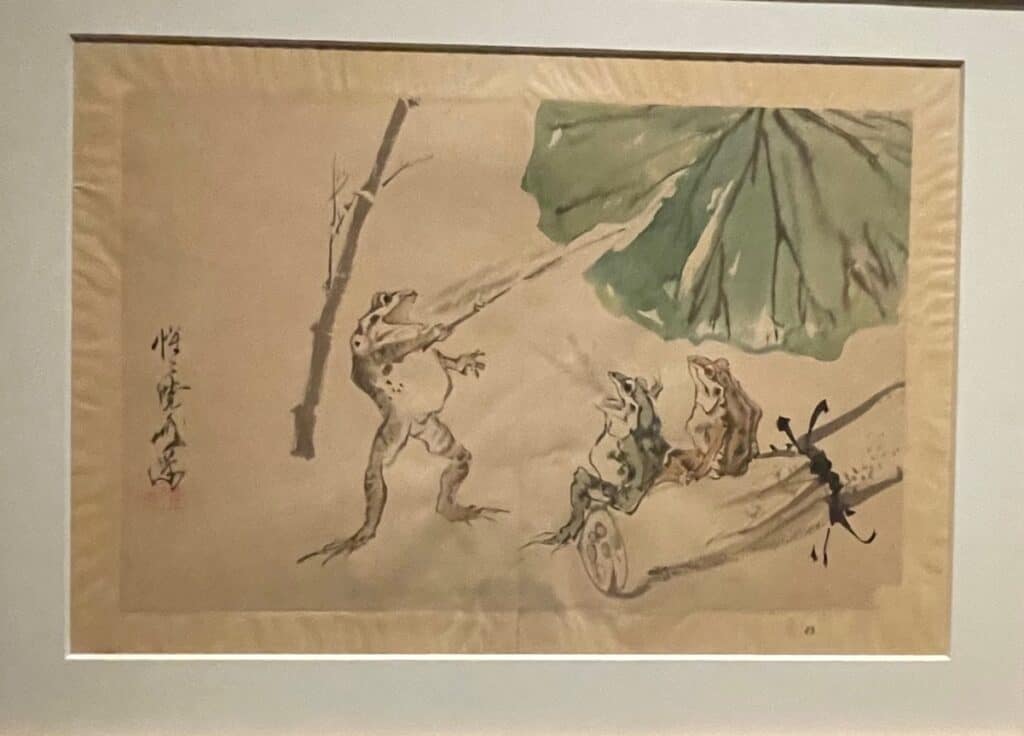

The paintings in the exhibition are often political and use animal metaphors for some of the more primal instincts of humans, with the ‘proles’ of 19th Century Japan represented as frogs, and images featuring crows, tigers, mice and elephants.

Fashionable Picture of the Great Frog Battle (1864) is a metaphor for a battle between a clan allied to the Tokugawa fighting the rulers of Choshu domain, a region of Japan opposed to the Tokugawa government.

Frog School (early 1870s) depicts a frog teacher giving a class to 2 frogs sitting on a wooden log, pointing at a lotus-leaf wall chart. In 1872 Japan established a national educational system and opened the first elementary school in Tokyo, with teaching following Western methods including wall charts.

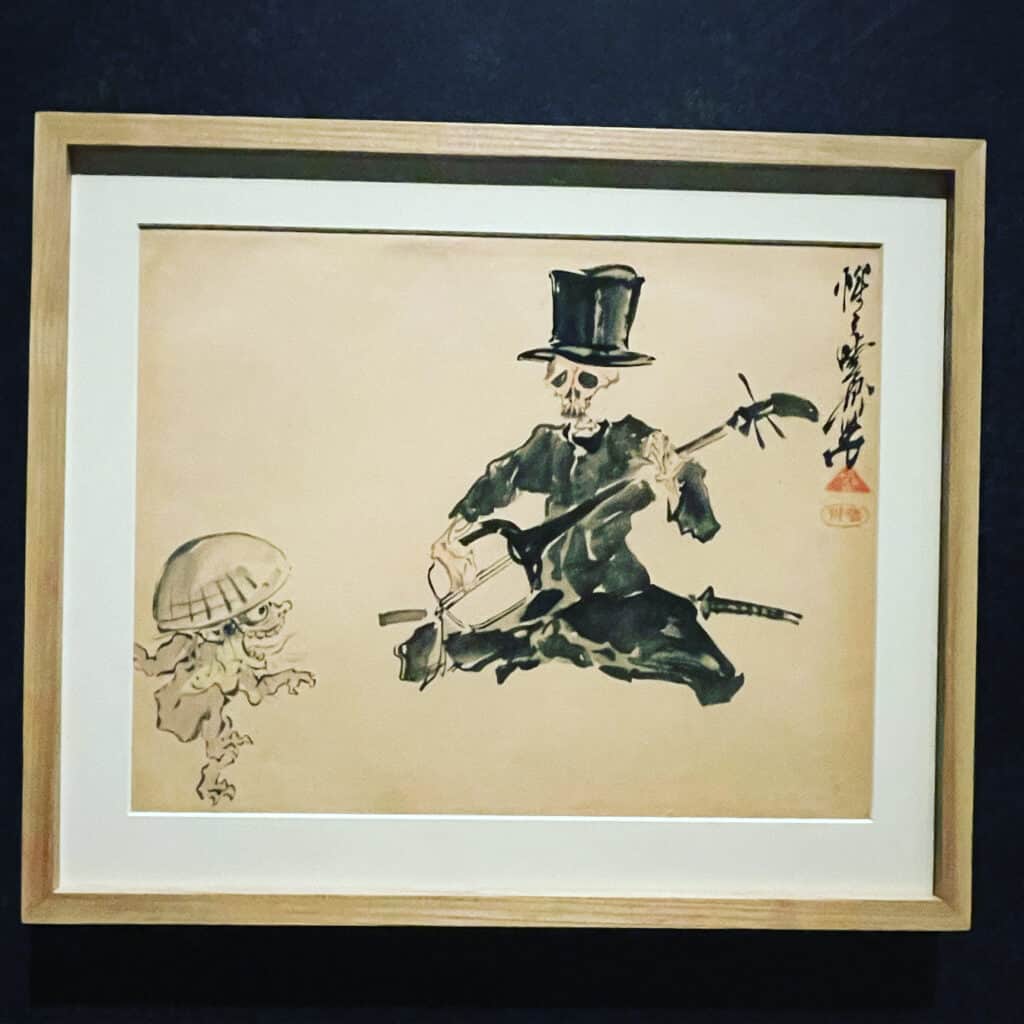

Skeleton Shamisen Player in Top-Hat with Dancing Monster (1871-78) shows a Top-Hat wearing skeleton playing a Shamisen to a small ghoulish character. The Top Hat in the image refers to the arrival in Japan of Westerners and their unusual fashions, while the Skeleton appears to be a visual way of reminding us of our own mortality.

Many of the images refer to the arrival in the mid-1800s of westerners in Japan, and some are tongue in cheek and downright cheeky, such as an image of a man farting, with humorous results which reveal Kyosai to be sort of a Japanese version of the 18th Century British printmaker, cartoonist and pictorial satirist William Hogarth.

Some of the most interesting images are of calligraphy and painting parties, such as Calligraphy and Painting Party (Shogakai), (c. May 1876–spring 1878). One such party in 1870, known as a ‘Shogakai’ (a commercially organised party at which painters and calligraphers produced spontaneous creations, and often ended in drunkenness), had ended up with Kyosai being taken to prison. Kyosai became known for his outlandish behaviour as his talent as an artist.

There was a cultural exchange between 19th century Japan and Europe, with artists such as Whistler and Van Gogh visibly influenced by Japanese woodblock printing and art, and Japanese artists such as Kyosai influenced by European contemporary art.