Coinciding with Artissima (Turin), one of the most important Italian art fairs, Marinella Senatore inaugurated her solo show at Mazzoleni Gallery, a reference point for modern and contemporary art in Italy and abroad. MAKE IT SHINE presents a vast selection of artworks by Senatore — from light-sculptures to pencil drawings, the exhibition greatly translates the artist’s multidisciplinary nature and her engagement with people.

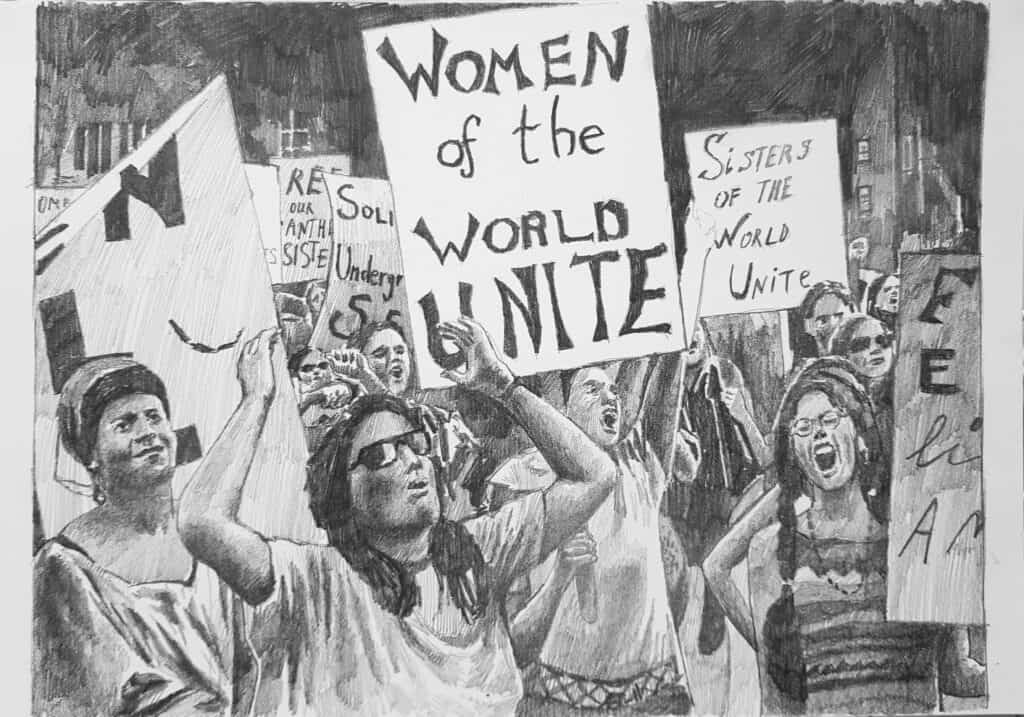

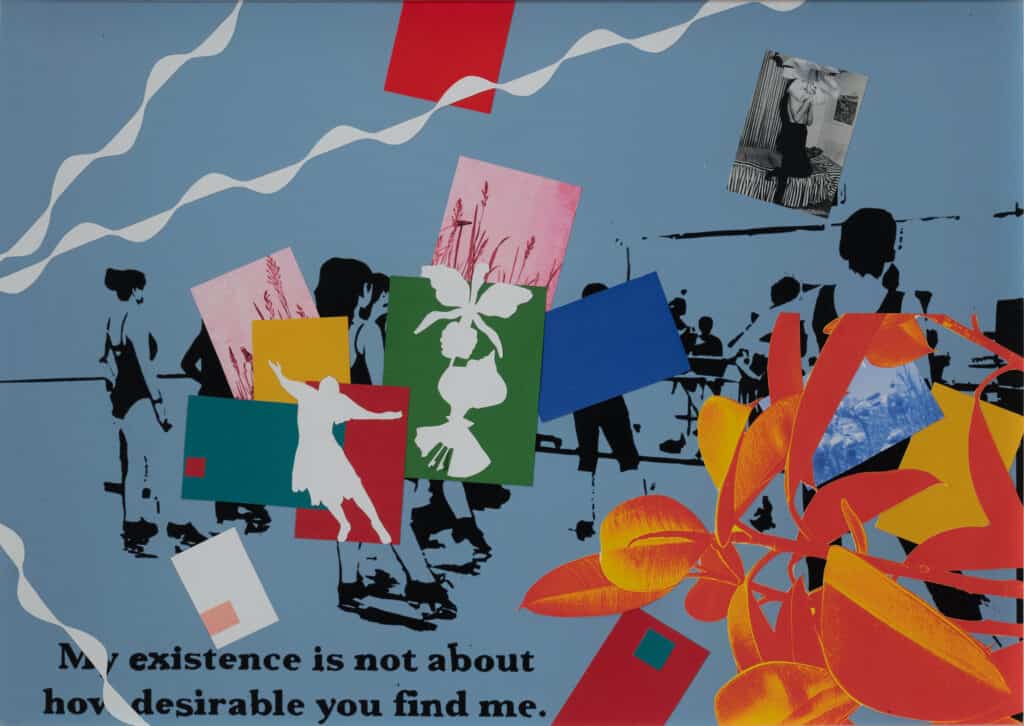

Senatore’s oeuvre is marked by a strong sense of how social engagement can be empowering, bringing about an actual social change. In MAKE IT SHINE visitors clearly perceive the strong sense of community characterising the artist’s creative process, and her need to include and welcome everyone in a project. The display starts from the famous Luminarie, light-installations belonging to the Southern Italian baroque culture, which Senatore reinterprets in a political way — they are a new monument, for the people, for every person. The exhibition continues following a chronological order including paintings, installations, collages, embroidered banners and pencil drawings, often accompanied by strong statement talking about feminism, revolution, human rights.

Let’s start from MAKE IT SHINE, your solo show at Mazzoleni Gallery in Turin. How did you conceive this journey through your multi-layered practice?

It was important to come back to Italy with a solo show and I wanted it to speak to a vast public, not just to the art system. I opted for a chronological order that could recount who I am now, and what is relevant to me. That’s why I display so many languages, which are still current in my practice. The exhibition begins with intimate works, dear to certain aesthetics important to me, such as Arte Informale in Italy, or Colour Field painting in the US. There’s also a great focus on the element of light, that entered my paintings after I had explored it as a director of photography for movie sets. Furthermore, I’m exhibiting collages and drawings, a storytelling tackling topics such as social justice, white supremacy, feminism. I felt the need for a multi-practice like mine to be considered by the market — I’m very linked to institutions, with commissions worldwide, but my work doesn’t belong exclusively to the curatorial or institutional field.

Marinella Senatore (1977) Un Corpo Unico, 2020. Acrylic, printing and collage on canvas, 120 x 120 x 4 cm (60 x 40 x 4 cm each, 6 pieces), 47 1/4 x 47 1/4 x 1 5/8 in. Courtesy The Artist, Mazzoleni, London – Torino

What kind of difficulties have you faced in the art market?

I am an activist, every day and in every moment. This gets difficult because the idea of creating participatory artworks that can also be commercialised is ‘stigmatised’. In this, I’m a trailblazer, at least in Italy I’ve been one; when I started, in 2006, Italian curators often asked me ‘but where is the artwork?’. And yet in Italy we do have a great legacy of relational art and social practices — think of Maria Lai or Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Social Theatre, just to mention a few. Being multidisciplinary is another obstacle, as the art world identifies you with your medium, not with your practice, whereas it’s through the latter that I want to tell what I do.

When did you start considering becoming an artist, a multidisciplinary one?

My background is already multidisciplinary: I studied Art at the Naples Academy of Fine Arts, then I attended the National Film School in Rome, and studied music at the State Conservatory in Italy, playing violin in professional orchestras, too. From classical music to film, I realised pretty soon that the choral structure of a work was extremely significant to me. Being multidisciplinary is still pivotal because languages are tools providing me with continuous opportunities to engage with others. The body and mindful movements play a key role for me, since 2012, when I funded The School of Narrative Dance, while at the same time I maintain a fascination for poetry.

Who had the most influence in your education?

Influences come from different disciplines, of course. I was attracted by Tim Rollins, Stan Douglas, but also Ana Mendieta, Félix González-Torres, The Living Theatre — a lot of practices that are not necessarily in direct dialogue to mine. There are writers and activists in this list too, such as Carlos Aponte, the leader of the Young Lords, just to name one; film directors like Fellini; the Italian Neorealism… Within this flow of references, I must admit it is traditions that really attract me. I’m not nostalgic towards the past. Rather, I believe the power of traditions lies in their activation of contemporary processes, which ultimately empowers and inspires the people.

Talking about traditions, I am thinking about your Luminarie, lighting structures from South Italy that call to mind religious and popular celebrations. How do you integrate folklore in your oeuvre?

When it comes to traditions I especially think about dance or popular music, which share a lot with the idea of the luminarie. I’m interested in the ability of such ephemeral architectures to create temporary spaces for gathering and assembling people. It’s a social phenomenon, not necessarily connected to religious rituals. With my light sculptures I like referencing back to the Italian Baroque, as the luminarie themselves do, overlapping narratives, suggesting spaces for assembly, for things to happen.

How can the past be activated through traditions?

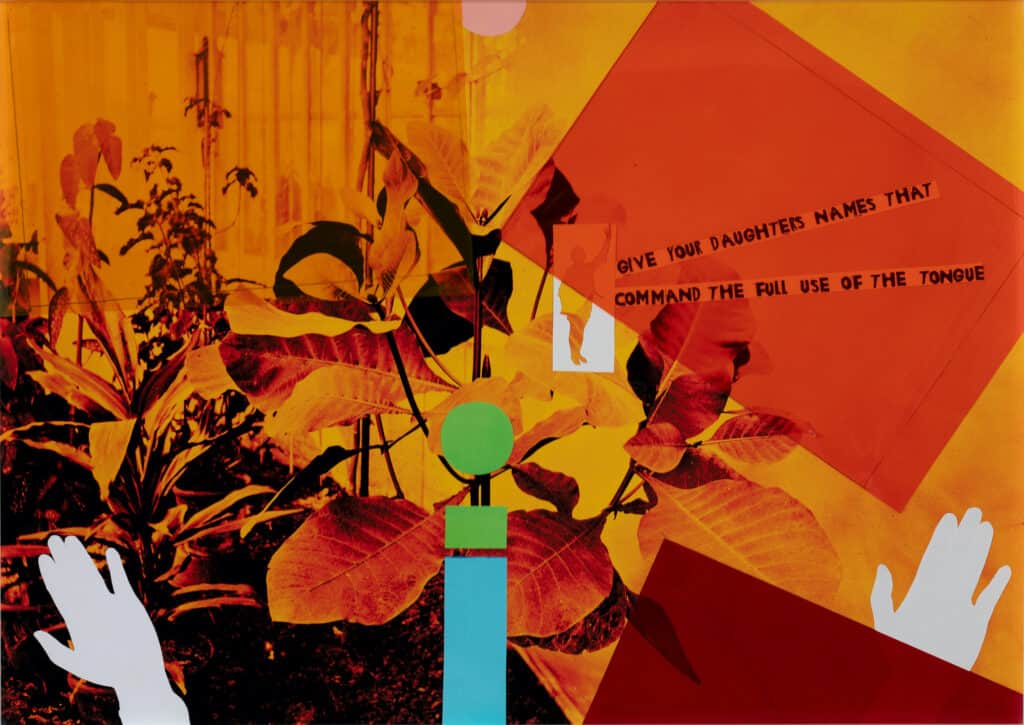

These works aim to create a space, a monument that’s here and now, for citizens, for the people. Especially when I insert them in the public space, they become a new kind of monument which goes against the conventional ones, too often dedicated to white males while almost never considering women or indigenous people, just to name a few. I also include text, a very important element in lots of my works. The words come exclusively from the workshops I host. This creates an invisible link between people that do not know each other, and may have different views or aesthetic imaginary. Yet, something that moved a specific community can mean a lot for others, too. It’s all about energy, and, even more, about emancipation and empowerment: these are the most crucial aspects that I always bear in mind when approaching a community.

In your works, you merge together several suggestions — shapes, colours, styles, words… Where do all these elements come from?

Things just come, easily; I never think about them happening in a specific way. There are so many texts, images, colours, sounds, flows of energy roaming in my mind at all times; I worked with more than six million people around the world just for The School of Narrative Dance! I keep an archive of every single meeting, workshop, proposal that I do, and I use it to activate a dialogue. It means everything to me: it preserves the participants’ energy and incorporates my contributions that come out working with them. The archive also contains old pictures from magazines, or imaginative landscapes that don’t necessarily belong to history or chronicles. This mess is who I am, it tells the story of my process. Whether on the street or on a canvas, I unite all these elements in my mind, the possibilities, the energy, the suggestions that people give me. This process itself generates a lot of energy, especially when you merge very dissonant elements as life is and the end.

I noticed hands often come up in your work, from collages to performances, as a symbol of rebellion, or a helping hand. Have you ever thought about it?

Hands are a very recent discovery in my iconography. I’ve always used them to portray people or myself within my artworks. I guess at the beginning it was more of a natural resource. At the end of this exhibition, I realised how often and in how many different media do they recur. I am focusing a lot more on the possibilities of linking space, materials, people, energy, words, and I’m approaching this in a very physical way. Furthermore, I am working on somatic choreography and mindful movements, also during The School of Narrative Dance performative events around the world. Physicality seems very relevant at the moment.

I was intrigued by the story you recounted in Turin about a blind person acquiring one of your paintings. It is as if the artwork did not stop at its aesthetic level. How important was this experience?

It really came as a surprise because in Italy, notably, we’re not used to welcoming blind visitors at private galleries, not even in museums, or at least not as often as it happens abroad. I say this with sadness in my heart because I abhor that so many people feel excluded, but definitely they are. Think only of video-art or exhibitions, even in public museums, where they can access physically but have no translations. In the UK, for example, you find those very easily, both for deaf and blind people. My practice is always concerned with inclusion, it influences my choice of materials and shapes. Participation, indeed, is not exclusively linked to methodology, it’s more of a concept, it’s my research. At the same time, I felt the need to focus on light and matter as physical and emotional experiences.

Where do you place your body in the horizontal learning procedure you adopt? Can you tell us more about how you began with this non-hierarchical approach and why is it so important?

I am a professor, it’s the most political part of my work. I don’t do it for money and it takes up a lot of time, but I’ve always looked with gratitude at this act of sharing. I come from the south of Italy, a beautiful land, but one where it takes courage to do what I did. I started teaching when I was 26 at a university in Spain. In love with The Ignorant Master by Jacques Rancière, I realised that hierarchical systems of educations were not functional for me — they don’t foster students’ emancipation from the limits of my knowledge. At the same time, I saw how closed the academic system still is: it’s hard to suggest a new structure which is more horizontal, while showing our limits as professor can really catalyse a self-education process. That’s why I founded The School of Narrative Dance in 2012, an open platform and a didactic project without hierarchies, not in the degree you may obtain, nor in terms of age — even kids can be teachers for a day. I want to challenge social structures and build a community based on the sharing of experiences, energy, emancipation and empowerment instead of race, ethnicity, age or social scale.

Who takes part in this project?

Most of the times, it is vulnerable people, or those belonging to stigmatised communities — from homeless to unemployed, illiterates and people with mental or physical disabilities — that reply to our open call. It’s not because I address it specifically to them, it’s the other way around! They want to come. Within the creative process, these participants, often considered by pre-existent social structures as ‘failures’ (and that’s how they themselves talk about their experience), stop being perceived as the vulnerable ones. Actually, they can become leaders, referents for a group which can include hundreds of people. This is so empowering that it rewrites completely the idea of vulnerability and the stigma it carries with it. It owns a lot to horizontality.

I thought a lot about the idea of a comfort zone, also in relation to the building of a community, a comfort-zone for stigmatised people. Horizontal learning also pushes established systems to their limits. How do you get out from yours?

My participatory projects start from an open call. You never know who will reply and participate and we don’t censor applications, unless something illegal is showing up. I faced a lot of controversial moments. I remember when in Dresden, Germany, I had to deal with the participation of a verbally aggressive group of people: from a legal point of view I couldn’t reject their application, but I knew they belonged to a far-right party. They are used, in fact, to exploit contemporary art to create polemics, if not riots. When they came to one of my projects, I found myself surrounded by people very far from my values. It was important for me to allocate an open mic to them anyway, to remain solid in who I am but to also grant a space for everybody. We all deserve it. It’s a challenge to collaborate with strangers and create a space of dignity for them; but there’s beauty in it because participants are the best teachers. It’s different every time, you get to know different cultures which may be already struggling in a negotiation with others.

Did they participate as a provocation?

Definitely. I was informed they do this very often, especially with artists coming from southern countries or Muslim artists. For me, it was an interesting and positive challenge. I like the idea of art creating a reaction; I like the debate happening through art because art is part of life, no more, no less.

I’ve been nomadic for 20 years, changing city and countries with every project. I always conduct research about the community beforehand, interviewing people from every field — from scholars to unemployed, teachers, sex workers etc. I started ‘Mapping the field’ in order to avoid creating pre-conceived ideas about different communities. It would be abusive otherwise, especially for an artist who claims to be actively creating participatory and community-based projects. It’s a long process; when possible, it also involves carrying out studies with social scientist to at least try to understand a certain community. Only at this stage I start sharing the open call for my workshops, using different methodologies according to the peculiarity of the community. This goes from joining independent radio broadcast to giving speeches in night clubs, job centres or other important hubs from the place I’m in. I invite people in their own language, which can mean dealing with hundreds of different texts sometimes, but for me it’s pivotal. It’s definitely a political action; I want everybody to feel welcomed. The result can even be just one participant, it doesn’t matter. It’s the act of inviting that must be inclusive. It cannot be called participatory if not everyone feels welcomed.