During the past couple of weeks, the London art world came back to life with a bang with the return of Frieze London & Frieze Masters, the RA Summer exhibition (held for the first time in the autumn), auction houses buzzing with sales and some brilliant independent gallery shows including Varvara Roza Galleries & The Blender Galleries ‘Mythos’, LUAP ‘The Unconscious Therapy’ and an all-woman group show at Soho Revue gallery.

Soho Revue gallery director India Rose and Purslane founder and curator Charlie Siddick have curated a beguiling group show of young women artists called ‘Thesmophoria’, inspired by an Ancient Greek women-only ritual. The ancient Greek festival was held in honour of the goddess Demeter and her daughter Persephone, and was one of the most widely celebrated in Ancient Greece, with the rites practised during it kept a closely guarded secret.

Upcoming artists Gina Kuschke, Ming Ying and Lily McRae all created work for ‘Thesmophoria’. All 3 are painters which seems to be evidence of a sort of Renaissance of painting amongst the new generation of art world rising stars. Edinburgh College of Art graduate Lily Macrae has exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy, and her dramatic paintings in ‘Thesmorphia’ take inspiration from cult movies and Old Masters and contain skilful foreshortening and chiaroscuro evoking Caravaggio. Ming Ying’s paintings use a palette of mostly greens and reds, colours which are often used in horror movies, with film colour psychology citing red as representative of anger, passion, rage and desire, and green representative of healing, soothing and perseverance. Ming Ying’s paintings for ‘Thesmorphia’ have a surreal dream-like quality reminiscent of a Toulouse-Lautrec painting of an absinthe-infused night of debauchery. Ming Ying graduated in 2020 from the Royal College of Art with an MA, and at this early stage of her career has already exhibited at the Saatchi Gallery and in New York and Shanghai.

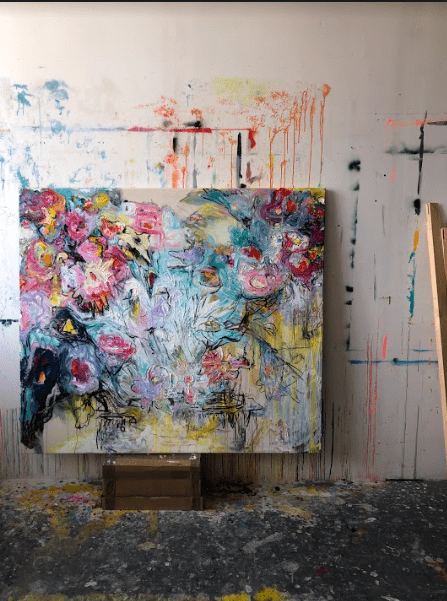

Gina Kuschke is a self-taught artist of South African origin who studied art history at the Courtauld Institute of Art. She moved from post-apartheid South Africa at a young age but her childhood memories of the country still surface in her art. Her colourful flower paintings are full of life and express a love of the visceral properties of paint as a medium.

I interviewed these talented young artists about their artistic practice and whether the historical gender imbalance between men and women artists is finally being redressed. Kuschke says: “Historically, a male-dominated world placed females in a position of inferiority by their “otherness” resulting in women being continually reduced to muse, witch or anomaly.” Read the interviews here:

Lee Sharrock: What was the path you took to become an artist, and can you give a brief summary of your work and the meaning behind it?

Gina Kuschke: I became an artist by accident. I never had the intention of becoming a visual artist full-time – this wasn’t something I thought was possible, even though my every spare moment since being a child was spent making things – art, music, everything – developing towards some sort of creative career. After we moved to the UK, I applied for the art scholarship to my desired school and to my surprise, I got it. I made my first art sale in my final year of school, of the largest triptych I’ve created to date. I went on to study a BA in Art History at The Courtauld Institute of Art, balancing studying whilst being signed in a record deal, making music full-time. I used some of the money I made from music to rent an art studio for myself in Hackney Wick which I still work out of today.

I then began as a self-taught artist, making work as often as possible and focused on connecting

with a network of artists and curators to begin navigating my way into being a professional working artist. My work questions the relationship between self, space and place. Exploring being born into post-apartheid South Africa and moving to the UK, in tandem with traumas I experienced as a child and adult, I hope to find answers on belonging through visceral mark-making and vivid bursts of colour.

Repurposing and reliving my most transformative and personal experiences in my work, simple childhood memories of daily life in South Africa are tainted by traumas that confessionally and unashamedly pour into the work. A combination of impasto eruptions of colour and naive figural line-based marks, with aggressive impulses of charcoal scrawls on raw canvas, play out this performative purge in seeking answers.

What’s the story behind your artwork featured in the group show at Soho Revue, and did you make the work specifically for the exhibition in response to the Greek myth of the theme?

Three of my works are featured in the Soho Revue x Purslane exhibition; “I see you in everything”, “I truly don’t know where we’re going” and “But Lilies still Bloom”. All of these works were created during the pandemic. I never have a solidified intention behind the work before making it; it is extremely instinctive and I allow the canvas to tell me what it wants. In a trance-like expulsion, I only realise after the work is made what is actually being represented. “I see you in everything” discusses carrying a defining memory through everything, though represented by a blossoming bunch of flowers, colourful, exotic and very alive, the work is an ode to this memory not diminishing any light or life. “I truly don’t know where we’re going” is an image of carrying the weight of all burdens on my shoulders, though it shows those as being left behind, hopeful to move forward into a future free of mind-clutter and anxiety. Finally, “But Lilies still Bloom” juxtaposes the image of lilies growing amongst dirt exploring the nostalgia of beautiful things growing out of harsh conditions.

This is an all-woman show. Why do you think women have historically been so underrepresented in museums and gallery shows, and have often been relegated to the role of muse when they were artists in their own right (see Frida Kahlo and Lee Miller as examples). And do you think this is imbalance is changing with your generation of artists?

Women have been underrepresented full stop – this is not unique to the history of art. Historically, a male-dominated world placed females in a position of inferiority by their “otherness” resulting in women being continually reduced to muse, witch or anomaly. I definitely believe that we are living in a time where we are seeing the beginnings of the discussion of a movement towards a shift in balance between women and men, however I do not believe that the shift is powerful enough yet. The art space feels much more open and available to female artists as a serious prospect, though we still only hear of too few well-known culture-shifting female artists. A reason for this is because the institutions are still mostly being run by males. I believe the actual shift will only truly happen once a new generation of females can actually sit in those seats of power and begin the discussion in a totally different way. This is in action and it is an exciting time to be a young female working artist, being part of helping this shift in balance for future generations.

Can you tell me a bit about your artistic practice, inspirations and the materials you use?

The work is entirely intuitive and impulsive, with little to no planning before beginning, always working large scale and pushing outside my comfort zone. I allow my instinct to drive every aspect of what is a very confessional work and I always try to tap into a place where the canvas tells me what it wants. If I am not able to reach this state of ridding myself of all conscious thought before creating the work, I won’t attempt to paint. I use raw canvas and oils mainly, with the additions of other materials such as charcoal and pencil running through the work too. I’m currently exploring pushing my work outside of these boundaries into more unconventional spaces. Music and dance inspire me to work as they help me access places otherwise hard to reach, my studio acting as my church and stage – I always have ear-achingly loud music blasting, some open floor space to play in and for bonus fun, red wine.

What was the path you took to become an artist, and can you give a brief summary of your work and the meaning behind it?

Lily Macrae: I never really planned the path to be honest, it was always what I loved the most and had a lot of creativity in my home growing up. I was always encouraged to pursue it despite it being quite unreliable at points. I visited the Edinburgh College of art degree show every year I could and then ended up studying there myself and from then I’ve been working from my studio in Glasgow in a warehouse right by the river Clyde.

The core of my practice, both conceptually and in terms of process is exploring that space in between the past and present; and my work has always been rooted in painting. I make large scale works which sit somewhere in between figuration and abstraction and inherit narratives and often appropriate both motifs and compositional elements from paintings of old Masters. It’s the power, gesture, light and storytelling in these primarily Baroque works which draws me in. I want to play with the traditional intentions of this imagery and what it means in the contemporary sphere.

What’s the story behind your artwork featured in the group show at Soho Revue, and did you make the work specifically for the exhibition in response to the Greek myth of the theme?

The works I’ve got in the show were actually painted during lockdown. I have two large pieces, one of which the imagery is partially taken from these deleted film stills of a pie fight in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove (1964), and also from a Michelangelo Caravaggio painting ‘Supper at Emmaus’ (1606). The other work was taken from The Triumph of Bacchus by Diego Velázquez (1628). Both are an exploration into feasting and the ritual behind the bacchanal in art history, particularly during a time when we were longing for the contact of others but could only surveil each other from a ‘social’ distance. During the pandemic, it was a ceremony we all usually share but had to do without.

Myth and stories from Old Master’ paintings are a theme that always runs through my work, so although the work wasn’t made specifically under the theme of ‘Thesmophoria’. I felt the whole premise of the show completely fit with my practice particularly in terms of the ideas of ritual and ceremony. In particular, relating to the ceremonial act and process of actually applying the paint to the surface.

For me, storytelling is innate in painting, and in particular within figuration so the link to ancient myth and story was something that really intrigued me.

This is an all-woman show. Why do you think women have historically been so underrepresented in museums and gallery shows, and have often been relegated to the role of muse when they were artists in their own right (see Frida Kahlo and Lee Miller as examples). And do you think this is imbalance is changing with your generation of artists?

I think that it is changing yes, in terms of big institutions it has a long way to go still but with our generation, I think it’s already changing. The most inspiring part of it is that women are supporting women at all levels of the art world and that feeling of community is incredible – that is what has been so incredible about this show is the opportunity to work with such talented strong women.

I feel like women have been underrepresented in all spheres of life until more recently because men have been running the show, but it’s exciting to see more and more female artists whose work I love being represented and realise that it is happening slowly, and it is possible.

Can you tell me a bit about your artistic practice, inspirations and the materials you use?

My practice encompasses mainly drawing and painting, I suppose I’m quite traditional in that, sense, I just feel like painting is a puzzle that I’ll never get bored of. I usually work on a really large

scale, so that the figuration within my work is almost life-size. Before my larger works, I start with these small abstracted studies and drawings, just to work out colours – I sort of think of them as a section of a larger work, just one brushstroke or captured moment.

I work mostly in oil paint, and paint in an almost negative way; covering the surface in one colour and then rubbing back through with my hands and brushes, creating a range of different tones within that one colour. This practice of revealing what lies beneath really interests me; I’m interested in this idea of the excavation of memory, how to represent something that is inevitably lost over time. Using painting as a way to reveal or uncover something that has been forgotten, I feel painting can be both a process of construction and excavation.

I paint most effectively in these short energetic bursts, otherwise, I find I lose the spontaneity of it all, and the actual act of painting itself is just as important to me as the subject. This fleeting nature of the painterly gesture is something I find entrancing – I’m constantly battling within that space between figuration and abstraction. I want to almost capture an image within the spontaneous gesture and quite often the narrative follows that.

I go through phases of being a bit obsessed with stills from certain films and draw a lot of inspiration particularly for compositions from them and from figures in Old masters’ paintings. At the moment I can’t get away from Caravaggio’s work. I generally just collect anything which catches my eye and create my own compositions from a mixture of sources.

What was the path you took to become an artist, and can you give a brief summary of your work and the meaning behind it?

Ming Ying: I am from Beijing, China. I accepted professional art training from my high school in Beijing, although it is quite different from the UK, I have gained a lot in realistic art skills. After that, I continued my studying on painting at UAL and then at RCA. The education from the colleges helped me widen my cognition of art and gradually develop my art language into an intact and mature system. From that study, I have formed my own way of creating artworks as a professional artist.

In general, my paintings reflect feelings of alienation or marginalization which arise out of the fact that individuals find themselves distanced, more so now than ever, from their surroundings. The phenomena results in vulnerability, homogeneity and loneliness. With these concerns in mind, my works aim to depict and unpick these feelings.

What’s the story behind your artwork featured in the group show at Soho Revue, and did you make the work specifically for the exhibition in response to the Greek myth of the theme?

In the beginning, Charlie invited me to join the show and showed that the artists are chosen based on each one’s painting language, the curating perspective is to make four of us are like a circle of painting’s development – from abstract to semi-abstract to figurative. So I can foresee that the viewers will be immersed in the connection between each of our works when they visit the show.

As I prepared for the show, I chose the works describing the female as a protagonist in different scenes. In particular, one of my works happened to depict a group of people around a woman who is like giving a speech, it seems like a festival occasion to celebrate something which echoes the theme of this show. The three works are created in diverse narratives based on the female perspective, so I chose them to show in the gallery.

This is an all-woman show. Why do you think women have historically been so underrepresented in museums and gallery shows, and have often been relegated to the role of muse when they were artists in their own right (see Frida Kahlo and Lee Miller as examples). And do you think this is imbalance is changing with your generation of artists?

In the past, due to many external reasons such as female’s role in society or social institutions, there were few women engaged in art, and the main force in the art circle was mainly men. Therefore, as a minority, women had so many disadvantages as artists. Many talented women are hard to be seen by the public, and the public even prefers to pay more attention to their emotional life or gossip at that time.

Compared with them, we are born in a fantastic era. One after another feminist movement and more and more female art practitioners have greatly reversed the situation. In recent years, the status of female artists has been consistently improved. We can see that almost half of the outstanding contemporary artists are women. We are benefiting a lot from our predecessors’ efforts, we are so lucky that we only need to devote ourselves to making works. Unlike the prejudice and disadvantages that occurred for previous female artists, we are witnessing an era of the rise of female power.

Can you tell me a bit about your artistic practice, inspirations and the materials you use?

All of my paintings are oil paintings, oil is always my favourite compared with other paint materials. During the past long special time, loneliness and desire not only affected me, a London-based foreign artist, but also had a strong impact on people of different races, cultures, and distinct social classes. In my practice, my references originate from people’s quotidian moments, flashy social scenes, drama and films. By employing distorted strokes, passionate colour and different colour layers, I am able to establish romantic and psychedelic scenes that are based on the real world, implying a vision of desire. The characters’ faces are often blurred by impasto paint which indicates their loss of identity in the loud environments in the pictures. No matter how bright and vivid the scenes are, the characters always present a sense of alienation. I am trying to create a dreamy scenario that toes the line between figuration and abstraction in my work, forming a world that is parallel to, yet separated from reality.

The expression of this kind of flowing way comes from a philosophic idea that all of conditioned existence is in a constant state of flux. The idea, in the eyes of Eastern Buddhism, is called “Impermanence” or named as “Positive and Negative” by Taoism. Heraclitus supports the idea with the word ”Change”. All of the flowing lines, shapes and tortile movements are used to reflect the ideas, and furthermore, all changes are conditional and interdependent in relation to our inner thoughts.

The works imply that it seems no one can escape from their alienation or marginalization in this rapidly changing world.